Charting the Chesapeake 1590 - 1990

- Introduction

- Maps for Mariners

- Charts for Marylanders

- Chartmaking I: Copperplates to Computers

- Chartmaking II: Surveying the Seen and Unseen

- The Language of Charts

- Cartographers of the Chesapeake

Chartmaking I: Copperplates to Computers

The Copperplate Process

Map and chartmakers preferred to use copper for engraving

because it was stable, yet soft enough to permit correcting.

They used copperplates for map and chart reproduction for

well over three hundred years, during the seventeenth,

eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries. This process

reproduced maps with intricate detail and tone

variations.

The process involved the following:

- The chartmaker incised the features of the chart into the surface of the smooth, polished copper plate. Using a sharp tool, he cut the lines, removing a narrow vee-shaped section from the surface. This was a painstaking, slow, and expensive procedure, made even more difficult by the fact that it had to be done as a mirror image.

- The chartmaker applied ink to the entire surface of the copperplate, making sure the ink filled the incised design.

- He wiped off the excess ink, leaving a small amount in the incised design and lettering.

- Next, he placed a sheet of paper over the plate. The paper was slightly moistened to make it more flexible.

- The chartmaker placed padding (often sheepskin) over the paper, pressing it firmly against the paper and plate so that the paper made contact with the inked incised areas. This was usually done by racking the plate, paper, and padding between metal rolls.

- Finally, the chartmaker removed the padding and stripped away the paper which bore ink from the incised areas.

William Blaeu employed the best pressmen, engravers,

scribes and colorist in the Netherlands. His types were

clean and well cut while his paper was heavy and of good

quality. Blaeu designed and built an improved printing

press.

Reproduced from The Story of Maps by Lloyd A. Brown,

1949.s of the tidewater area published from 1612 to

1673, it was not terribly useful as a chart since it

lacked the detailed information needed for navigation

An early woodcut illustration of a cartographer at work.

From Paul Pfintzing's Methodus Geometrica, first printed

in Nuremberg, 1598.

Reproduced from The Story of Maps by Lloyd A. Brown,

1949.

Lithography

Lithography is a printing process that was introduced in the

United States from Europe during the early years of the

nineteenth century. Since the process was faster than

copperplate engraving the U.S. Coast Survey used

lithographic printing to fill the great demand for charts at

the start of the Civil War.

The process involves the following:

- The image to be printed is rendered with an oily or waxy material on a flat surface. Early lithographers used a smooth stone for this purpose while sheet zinc or aluminum is used now. As with copperplate engraving, the chart is drawn as a mirror image.

- The chartmaker dampened the stone, then rolled ink over its surface. The ink adhered to the image but was repelled by the dampened parts.

- Placing a sheet of paper on the stone, the chartmaker passed the stone and paper though a press.

- He peeled away the paper which carried the inked image.

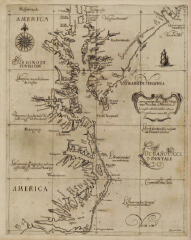

Carta Particolare Della Virginia Vecchia E Nuoua

Sir Robert Dudley

Florence, Italy, 1646

Huntingfield Corporation Map Collection, MSA SC

1399-1-536

This was the first chart of the Chesapeake area to use the

Mercator projection. It and others in the rare marine

atlas Arcano Del Mare are considered among the most

beautiful engraved charts of the seventeenth century. The

copperplate engravings in the atlas took twelve years to

make and used five thousand pounds of copper.

Virginia partis australis...

William Janszoon Blaeu

Amsterdam, 1640

Huntingfield Corporation Map Collection, MSA SC

1399-1-563

This is an example of a beautifully engraved chart from

the Dutch publisher William Janszoon Blaeu and his sons

John and Cornelius. Blaeu was a highly respected man of

science who held the title of Map Maker to the Republic.

Yet many of his maps and charts, such as this one, are not

scientifically accurate. Some scholars believe that Blaeu

was a shrewd businessman who made two kinds of charts: one

to please the eye that tended toward bright colors and

gold leaf; the other for seamen and officials who knew and

demanded the best in scientific documents. Blaeu's working

maps and charts were most likely worn out or destroyed as

a safety measure, while his beautiful maps and atlases,

because they were locked up in a gentleman's library and

never disturbed, have survived.

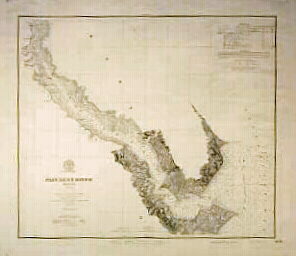

Patuxent River Maryland, Lower Part

U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey

Washington, DC, 1897

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Admin., National Ocean

Survey

This print was made directly from the a copperplate. It is

the same basic chart as the 1859 preliminary chart of the

Patuxent River but it includes topographic

characteristics. It also includes two lighthouses that did

not exist in 1859, Drum Point Lighthouse and Cedar Point

Lighthouse, marking the entrance to the Patuxent River.

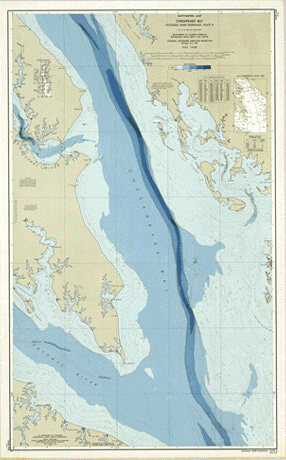

Bathymetric Map -- Chesapeake Bay: Potomac River

Entrance--Plate 8

National Ocean Service

Washington, DC, 1970

Huntingfield Corporation Map Collection, MSA SC

1399-1-743

This colorful map is an example of a modern printing

chart. Its coloring illustrates the Chesapeake Bay as a

drowned river valley with a narrow, deep channel. The Bay

was formed when the Susquehanna River flooded 15,000 years

ago with the melting of the glaciers in the last ice age.

|

This web site is presented for reference purposes under the doctrine of fair use. When this material is used, in whole or in part, proper citation and credit must be attributed to the Maryland State Archives. PLEASE NOTE: The site may contain material from other sources which may be under copyright. Rights assessment, and full originating source citation, is the responsibility of the user. |

© Copyright December 15, 2023 Maryland State Archives