Charting the Chesapeake 1590 - 1990

- Introduction

- Maps for Mariners

- Charts for Marylanders

- Chartmaking I: Copperplates to Computers

- Chartmaking II: Surveying the Seen and Unseen

- The Language of Charts

- Cartographers of the Chesapeake

Cartographers of the Chesapeake

The cartographers of the Chesapeake were artists, explorers, businessmen, sea captains, and scientists. Whatever their backgrounds, however, their work combined the art of interpreting the bay's physical features and the science of plotting the exact location of those features.

John White

John White, an Englishman, was an artist and member of the

1585 expedition to establish the Roanoke colony, off the

coast of present-day North Carolina. He and Thomas

Harriot, philosopher, naturalist, and mathematician, were

employed to gather information about the New World.

White's drawings of Eastern Woodland Algonquain Indian

life were used with Harriot's notes in

A Brief and True Report of the Newfound Land of

Virginia. White's granddaughter, Virginia Dare, was the first

child born of English parents in the New World.

What did John White look like? We do not have a clue since

no sketch of the artist himself has survived. Yet because

of John White's drawings that were published in addition

to his map, we have a glimpse of Indian life in the

Chesapeake region four hundred years ago.

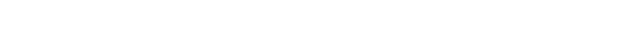

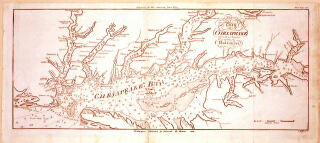

America Pars, Nunc Virginia Dicta... John White Frankfurt, Germany, 1590 Huntingfield Corp. Map Collection, MSA SC 1399-1-207 John White's map was the first to identify the bay by its present name. (You can find the words "Chesepiooc Sinus" in the middle right side of the map.) White's map shows only the mouth of the bay, since the remainder had not been explored by his expedition. The decorative touches in White's map reflect his training as an artist and contrast with the scientific approach employed in modern chartmaking.

Augustine Herrman

Augustine Herrman was born in Prague, Bohemia

(Czechoslovakia) in 1605. His family eventually settled in

Amsterdam, a leading center of commerce and trade at that

time. By 1644, Herrman was an agent for a large shipping

company in New Amsterdam (New York). He then established

his own trading company and also engaged in farming,

fur-trading, and land speculation. By the mid-1650s he was

one of the leading merchants and citizens of New

Amsterdam.

In 1659 Herrman applied to become a resident of the

territory of Maryland. Lord Baltimore approved the request

and in 1662 Herrman received the first of several

extensive grants of land, which totaled between twenty and

twenty-five thousand acres. Herrman established his

residence, called Bohemia Manor, on a 6,000 acre tract

located on both sides of the Elk River in present day

Cecil County. First surveyed in August 1661, it was

granted to Herrman by patent of June 19, 1662, in exchange

for his promise to make a map of the territory.

Herrman conducted surveys for his map from 1659 to 1670

and spent the next several years plotting, drafting, and

ornamenting the map, He sent his finished manuscript to

London, where William Faithorne engraved it in 1673.

The Herrman map was copied and adapted by mapmakers for

more than a century after its publication. It was

especially important in helping to solve the boundary

disputes between Maryland, Virginia, and Pennsylvania.

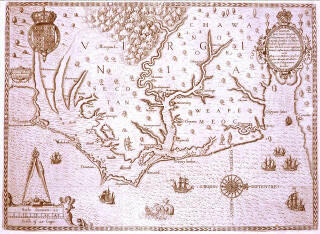

Virginia and Maryland as it is Planted and Inhabited this Present Year 1670, Surveyed and Exactly Drawne by the Only Labour & Endeavour of Augustim Herrman Bohemiensis Augustine Herrman London, 1673 [1970] Reproduction of facsimile from the Huntingfield Corporation Map Collection, MSA SC 1399-1-679 Herrman's map was the prototype for charts of the Chesapeake for over sixty years. Based on his own surveying and sources, it had more information for the navigator than anything else publicly available. Its navigational use, however, was hindered by its four-sheet format.

Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler

Ferdinand Hassler was a Swiss mathematician who had

extensive surveying experience. When the U.S. Congress

authorized an official Survey of the Coast in 1807,

Hassler, who was between teaching appointments in

Philadelphia, became interested in the enterprise. After

Hassler was appointed to the post in 1811 he immediately

set off to Europe where he had special instruments made to

do the survey work.

Hassler was the first superintendent of the U.S. Coast

Survey and insisted on an unprecedented level of

scientific accuracy. His surveyors carried out their

triangulation -- fixing the relative positions of

different locations of the earth's surface by use of a

network of triangles -- according to strict geodetic

principles. This careful approach delayed the production

of charts and thus brought criticism from individuals

within the government. Yet Hassler's legacy was in the

sound scientific base of the bureau's work. While it was

expensive and time consuming, U.S. charts became the

standard for the world.

Edmund Blunt

Edmund March Blunt was born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire,

in 1770. He became America's most notable early

hydrographic with the publication in 1796 of the

American Coast Pilot, the first book of

sailing directions compiled and printed in the United

States. Blunt continued to publish updated volumes of the

American Coast Pilot, describing all coasts

of the United States.

Blunt's sons, Edmund and George, devoted their lives to

charting and the sea as well. Edmund was hired by the U.S.

Coast Survey for whom he worked on triangulation of the

bay, among other duties. George Blunt became a publisher

of charts and nautical books in New York. He revised the

American Coast Pilot several times and was a

major force behind causing the federal government to

organize the Lighthouse Board. After the death of the

elder Blunt in 1862 and Edmund Blunt, Jr., in 1867, George

sold the copyright for

American Coast Pilot to the U.S. Coast

Survey.

The Bay of Chesapeake from its Entrance to Baltimore

Edmund M. Blunt

Newburyport, Massachusetts

Huntingfield Corp. Map Collection, MSA SC 1399-1-191

This chart was among the first prepared and published in

the United States. It showed both true and magnetic north,

a new feature for charts of the bay. (You can see true and

magnetic north marked beneath the work "Bay" in the center

of the chart.) It was also one of the earliest charts to

show navigational aids. (See Cape Henry Lighthouse in the

lower left of the chart.)

Cartographers for the National Ocean Service

Cartographers for the National Ocean Service (NOS) of the

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

compile and construct charts for about 2.5 million square

nautical miles of the nation's coastal waters, the Great

Lakes, and connecting waterways. They work with data from

surveys and other sources in constructing and revising

charts.

The work of modern-day cartographers is varied. Some

participate in surveys or assist with hydrographic

observations aboard ships of the National Ocean Survey

fleet. Others evaluate survey data to ensure it accuracy.

Cartographers today use aerials photographs to plan

extensive field surveys and to map shore detail. They also

operate special survey instruments and process data

through computers to determine exact positions of data. In

addition, they compute direction information obtained from

orbiting satellites. Experience cartographers engage in

research and development to devise improved cartographic

methods and portrayal techniques.

Cartographers today typically have advanced degrees and

experience in fields such as mathematics, astronomy,

cartography, engineering science or drafting, geodesy,

geography, geology, geophysics, meteorology, navigation,

oceanography, physics, and surveying.

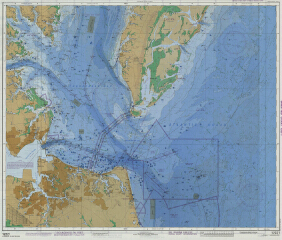

United States-East Coast, Virginia: Chesapeake Bay

Entrance

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

Washington, DC 1986

Huntingfield Corp. Map Collection, MSA SC 1399-1-747

This experimental chart was produced by the National Ocean

Service (NOS) of NOAA to examine possible improvements in

traditional charts. Among the changes proposed were to

highlight fish havens and disposal areas and to subdue

road designations and compass roses. It was submitted to

the International Hydrographic Organization conference in

1987. The National Ocean Service surveyed user

organizations for their reactions to the changes, some of

which were adopted while others were rejected. This

experimental chart was part of a continuing effort to

achieve worldwide standardization of nautical charts and

to improve chart usefulness.

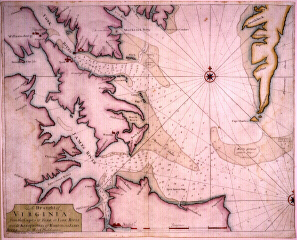

A Draught of Virginia from the Capes of York in York River

and to Kuiquotan or Hampton in James River Mark

Tiddeman

London, 1729

Huntingfield Corp. Map Collection, MSA SC 1399-1-29

Tiddeman was master of the British vessel

Tartar from 1724 to 1728. While patrolling

the mouth of the bay, he made extensive soundings which

were published in The English Pilot. The

soundings were the most complete available for the area at

that time.

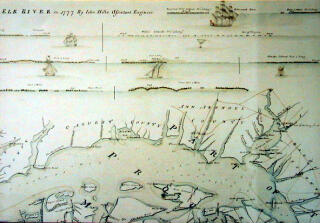

Plan of the Peninsula of Chesopeak Bay

John Hills

Unpublished manuscript, 1781

Copy of detail courtesy of the William L. Clements

Library, University of Michigan

John Hill's manuscript was the first surviving chart to

feature profile views of the shoreline. Such views were

helpful for coast piloting -- navigating within sight of

land -- and were widely used for seventy-five years. Hills

did his manuscript in pen and tinted it with water colors.

It was probably used by the British during the

Revolutionary War.

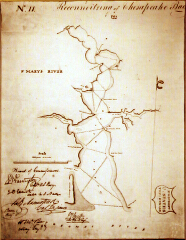

N. 11 Reconnoitering the Chesapeake Bay 1818

U.S. Topographical Bureau

Unpublished manuscript chart, 1818

Huntingfield Corp. Map Collection, MSA SC 1399-1-334

The War of 1812 called attention to the inadequacy of

charts furnished to the U.S. Navy. As a result, the

government organized surveys of the Chesapeake Bay and its

harbors. The survey included extensive soundings like

those shown here, crisscrossing the St. Mary's River.

Today teams of specialist rely on sophisticated instruments for measuring and analyzing the physical characteristics of bodies of water. Their forerunners were not so specialized, nor did they have the benefit of such highly accurate instruments. Early charts were based on data collected by explorers, navigators, sea captains, or military men. Their instruments often served two purposes: one for obtaining data to record on the chart and the other for navigating in conjunction with a chart.

Backstaff

Early mariners used the backstaff to determine their

latitude by measuring the altitude of the sun at noon.

Introduced by John Davis of London in 1594, the backstaff

was so named because, unlike the cross-staff which it

replaced, the user had the sun behind him when taking an

observation. The backstaff was also known as Davis'

quadrant.

Cross-staff

The cross-staff, forerunner of the backstaff, was used by

mariners to determine latitude at sea by measuring the

altitude of the sun at noon. Its chief drawback was that

it forced the user to look directly at the sun to take a

reading. From John Seller's

Practical Navigation, first printed in 1669.

Mariner's Astrolabe

The mariner's astrolabe was the forerunner of the

backstaff, quadrant, octant, and modern sextant developed

to measure the altitude of the sun or stars. A mariner

could determine his latitude by means of these

instruments.

The astrolabe consists of a graduated ring of brass fitted

with a sighting rule, pivoted at the center of the ring.

The astrolabe is suspended by the thumb or by means of a

thread from a shackle at the top of the ring so that it

hangs vertically. The sighting rule is then turned about

its axis so that the sun or star can be sighted along it

and the altitude read off on the ring.

The astrolabe was used from the late fifteenth century

until the end of the seventeenth century. It was of little

use for observations from the heaving deck of a ship at

sea but was of considerable use in charting the

approximate latitudes of new discoveries where

observations were made on shore.

Octant

The octant uses an eyepiece and mirror to measure the

altitude of heavenly bodies. It has an arc of one-eighth

of a circle, but its design permits the measurement of

altitude up to 90 degrees. Octants remained in use by

navigators until 1800 when they were replaced by sextants.

Sextant

Using a small telescope and an arrangement of mirrors, the

sextant allows the sailor to measure the angle of the sun

or a star above the horizon. Invented in the 18th century

by John Hadley, the sextant is used to determine a ship's

latitude.

|

This web site is presented for reference purposes under the doctrine of fair use. When this material is used, in whole or in part, proper citation and credit must be attributed to the Maryland State Archives. PLEASE NOTE: The site may contain material from other sources which may be under copyright. Rights assessment, and full originating source citation, is the responsibility of the user. |

© Copyright December 15, 2023 Maryland State Archives