The Use and Implications of Photographs for Mental Health Care Reform

- Introduction

- Almshouse Care

- Early Reform Attempts

- Commission Campaign

- Aftermath

- Exhibits October 6, 1908 Report

- Traveling Exhibition images

- Montevue Asylum Images

- Curator's Comments

Commission Campaign

The State Lunacy Commission initiated its documentary photographic campaign in August of 1908. It appears that Secretary Herring first employed a photographer from the Hughes Photographic Company to accompany him on his tour of Baltimore's almshouse, Bay View. This no doubt costly arrangement prompted the commission to find a more economical way to acquire photographic images for its campaign. Dr. Herring purchased a camera soon thereafter and began his tour of county institutions, making an initial photographic record of what he witnessed. A preliminary, incomplete set of photographs existed by the end of September.

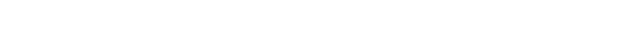

Herring captured the general themes the commission had railed against for decades. The topics of focus included the free use of restraints, chronic overcrowded conditions, dilapidated and unsound buildings, unsanitary conditions, lack of recreation, and the drawing of a visual parallel between an almshouse to a jail. Barred windows and manacled patients implied that mental illness was a punishment rather than a condition. Captions accompanying the images reinforced the argument, guiding the viewer in their interpretation of the photograph and providing additional insight into how patients were improperly cared for within the county institutions.

This initial series of twenty-six images appeared as the exhibit portion of a preliminary report Dr. Herring presented to Governor Austin T. Crothers on October 6, 1908. The typescript report and the images formed a nucleus around which a final comprehensive printed version would appear, with additional photographs, several months later. Fourteen almshouses and asylums from across the state appear within the photographs.

Herring allotted the largest number of photographs to the Montevue Asylum in Frederick County, and it is this institution that the commission found the most problematic. It had not always been this way. In 1884 the state health department lauded the asylum as a model institution which brought credit upon the county. Early Lunacy Commission annual reports also praised the conditions at Montevue as being exemplary. Yet by the mid-1890s, even a Frederick County grand jury suggested that the conditions could be improved for some of its patients. Reflecting the segregationist thought that often pervaded Progressive thinking it noted: "The enlargement of an adjoining building for the confinement and care of the Colored portion of inmates would in our opinion be of great advantage to the institution." Montevue accepted, along with payment from other counties, insane African Americans from throughout Maryland. Chronic overcrowding of black patients at this institution had been noted within the commission's annual report since 1895. It appears that a string of county commissioners viewed Montevue as the means to build up county coffers. Only the Frederick County commissioners steadfastly refused to endorse the concept of state care.

Dr. Herring made Montevue Asylum the focus of the Lunacy Commission's October 28, 1908, meeting. Though the conditions at almshouses were addressed broadly, the commission postponed making public conditions at Montevue until they could "go tactfully and win the co-operation of the County Commissioners, if possible." The commision decided to "adhere strictly to legal lines" but "to use the public press to expose conditions." They also discussed rescinding the license of the asylum if non-cooperation continued.

Toward the end of November, Herring began presenting an illustrated lecture to groups throughout Maryland, probably without identifying almshouses by location. The commission also lobbied the Maryland medical community in the pages of the Maryland Medical Journal, the voice of the Medical- Chirurgical Faculty, understanding that the medical community had key private and public contacts throughout the state that could influence state politicians. The March 1909 issue contained two exterior shots of almshouses on the Eastern Shore.

Maryland Psychiatric Society, 1908

The Lunacy Commission campaign and the photographs did act as a catalyst in the professionalization of psychiatry in Maryland. The crusade for better treatment of the pauper insane, prompted largely by the content of Dr. Herring's images, brought together both public and private practitioners interested in the state care issue. At the founding of the Maryland Psychiatric Society in November of 1908, the organizers hoped to discuss "practical questions relating to the care of the insane... and foster interest in bringing about state care in 1910."

An event in Baltimore afforded the first large-scale opportunity for great numbers of people and the press to view the images and educate themselves about Maryland's mentally impared citizens. The commission opened a three-day exhibition of its photographs, along with shackles and restraint devices, at Johns Hopkins University's McCoy Hall on January 20, 1909. The Maryland Medical Journal commented, "The exhibition is very creditable and is the first affair of its kind ever held in the country, so far as we are able to learn."

A DeKalb "Crib," c. 1905

The opening night proved to all that this was no ordinary exhibition. A brass concert band, composed of twenty young teenagers from the Home of the Feeble-Minded, serenaded the audience in advance of the speakers. Governor Crothers provided a symbolic endorsement speech as the initial remarks. Herring enlisted none other than Dr. Alfred Meyer, a nationally recognized psychiatrist and soon to be head of the Phipps Clinic, to deliver the keynote address. Speaking of county institutions, Meyer concluded that "they probably do as well as they and their constituents consider necessary. As to the actual results, the photographs and concrete records of Dr. Herring will have to speak...the almshouses perpetuate the wrong impressions which are at the bottom of a great part of the public indifference." Unfortunately, Herring thought the content of Meyer's paper went over the heads of most laymen present.

Dr. Herring's lantern slide lecture, on the other hand, was dramatically clear and straightforward. The Baltimore News assured its readers that photographs "taken in some of the hospitals where conditions were most squalidly unspeakable will be shown." Though we do not known which images Herring used, they were "views of the almshouses in the counties of Maryland and the State institutions, showing the marked contrast between the two systems of caring for the insane." Meyer later told Secretary Herring that he "was very much impressed with the exhibit you made and especially your demonstration [the slide show]. There can hardly be any doubt in my mind as to the success of the State-care issue."

Images from Montevue Asylum. View additional images

The Lunacy Commission's twenty-third annual report of 1908 revealed all. A notice of the lavishly illustrated publication appeared in the Baltimore Sun of April 18, 1909. The article noted that the photographs provided "a quick insight into the conditions of the county institutions...showing men chained to cells and others living in unhealthy surroundings...in almost every county little attention is paid to the insane and feeble-minded." The photographs stand in direct contrast with those presented of state hospitals where "everything is clean and wholesome." The Sun reserved its most detailed description for the views taken at Montevue Asylum, "the worst of all visited... [where] men are shown with their arms shackled, and one old negro is seen chained and shown lying on the floor in an unclean cell. Patients--men and women--are shown lying huddled up in blankets on the floor in the halls of the building." Photographs did not accompany the Sun article.

The Montevue photographs contained in the 1908 report built the strongest case yet for abolishing the system of county care. Commission members had made five visits to Montevue in the space of several months, more than any such institution, carefully seeking out the most incriminating images. Another series of photographs taken in January 1909 with flash equipment were the result of what may have been a surprise night time inspection by Dr. Herring.

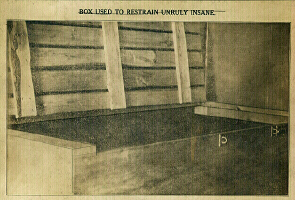

Three of the five photographs in the report depict interiors. One of the most damning is the portrayal of the sleeping accommodations for African Americans men. The benches in the central hall that served as a day room had been cleared to one side. Patients lie crowded on the hard wooden floor of the hallway with minimal bedding, save for thin blankets to ward off the night cold. The meagerness of this scene, notwithstanding the intangible factors of the lack of physical comfort, possible cold room temperature, and the altogether unwholesome atmosphere, speaks volumes about the inadequate care meted out by county institutions.

The second image clearly shows three African American men held in restraint. The barefoot man in the left foreground looks puzzled. His right hand thrust in his pocket obscures the fact that he wears shackles. A leather muff encloses the hands of the second patient, who looks squarely at the camera. The muff is at the optical center of the photograph drawing the eye to an object that was probably unfamiliar to the most of those viewing the image. A third patient his hands and allows allows the visitors an unobstructed view of his chains. The two attendants to the right stare at the camera, one appearing almost hostile. There is nothing to indicate why the patients are held in restraint. The expressions of all three is non-threatening, prompting one to question the need for restraints. Are they being punished for their insanity?

The last image may answer the question. This is the image that the Sun described above. Here an elderly man lies upon a thin mattress on the floor of a cell. A chain, attached to the grating of the window, leads to his manacled wrists. How could such a fragile, almost sickly appearing man warrant this treatment? Herring evidently hoped that those who saw the photograph would understand the inherent absurdity of these conditions, prompting a visceral reaction of outrage and support for state care.

Montevue Asylum, 1909 Before and After Photos

The photographs had the desired effect. In 1908, the Lunacy Commission characterized the conditions at fifteen county almshouses and asylums as very unsatisfactory; by 1910 that number had dropped to nine. To its credit, Frederick County acted quickly and decisively. The threat that the commission would revoke Montevue's license due to overcrowding may have have quickened their reaction. The county fathers endorsed state care and began to upgrade the conditions at Montevue during the interim before the introduction of state control. Redesigned wards for African Americans, with indoor toilets and bathing facilities, not to mention beds with mattresses in bedsteads, came as a result. No great efforts materialized at any other almshouse or asylum. Several Eastern Shore counties seemed especially reluctant to devote any additional funds to improving their facilities.

In May 1909, Lunacy Commission members with the assistance of state hospital officials and other experts began crafting proposed legislation to come before the General Assembly's 1910 session. Concurrently, consultation work began on the proper design for the additions needed at the various state hospitals. Two bills would eventually be put forward. The first would revise the State Care Act of 1904 that broadened the commission's powers. A second bill outlined the need for a $600,000 expenditure to expand the existing state mental hospital facilities, and to build a new facility for African Americans.

Opposition to the legislation soon appeared. Rumblings on a number of grounds came from physicians who ran private asylums. Under the proposed bill, if the commission determined that a state institution could provide better rehabilitative care they would lose their patients, with the result that some doctors at private sanitariums might be injured financially by the program of state care.

Herring's photographs themselves may have prompted opposition to the bills. The images shamed Maryland. As one citizen observed, "the last few months [Herring] has heralded Maryland to the country at large as a State where barbarities and cruelties are practiced upon its indigent insane, multiplying instances and exaggerating conditions."

Maryland State House, c. 1905

The opening of the 1910 session of the General Assembly in January marked the culmination of the Lunacy Commission's sixteen-month campaign. Dr. Herring took up temporary residence in Annapolis to personally lobby for the passage of the State Care bill during the three-month legislative session. To assist him in his effort, he once again organized a large exhibition of images and restraint devices in the Maryland State House. For the entire session the historic Old Senate Chamber served as the viewing hall for the photographs. The display of images was strategically placed but a few steps from both the House and Senate chambers. The Sun informed its readers that the "photographs show the cells and dungeons of the county asylums. The overcrowding and inadequate accommodations afforded these unfortunates are graphically portrayed by these pictures."

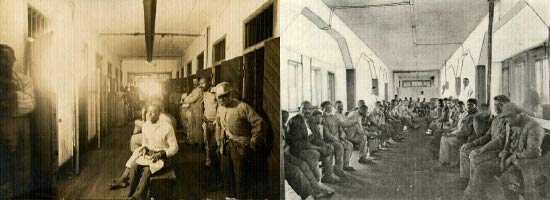

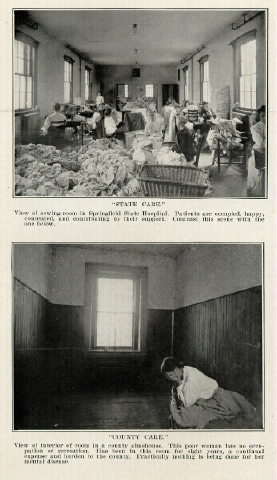

The commission contrasted the squalid almshouse scenes with complimentary views of Maryland state hospitals, where patients in the latter were engaged in work such as making shoes and clothing, and even printing and binding.

"State Care" and "County Care"

A February 9, 1910, state house meeting officially opened the exhibition. In advance of the speakers, Herring conducted personal tours of the displays while the brass concert band from the Home of the Feeble-Minded serenaded the gathering audience. An overflow crowd filled the galleries and halls of the House chamber. The governor, the comptroller, and both the Speakers of the House and Senate delivered speeches in support of state care. William L Marbury argued that "we cannot afford to have it said that the people of Maryland are neglectful of one of their highest obligations...the care of their own indigent insane--the most helpless of all mortals under the sun--our good State would be put to open shame in the eyes of the civilized world."

Less than two weeks later, the House unanimously approved the legislation. The bill passed without amendments by a vote of 98 to 0 on February 17, 1910. It was then sent to the Senate, where its passage proved to be more precarious.

Herring had made enemies along the way. Beginning what the Sun described as "one of the most protracted fights of the [legislative] session, Senator Peter J. Campbell of Baltimore, an ally of the private sanitarium owners, first rose and moved that all the words after "A Bill" be struck from the proposal. After three hours of heated discussion Campbell's motion was defeated. Senators then put forth several amendments to limit the power of the secretary. Most were thinly veiled personal attacks on Herring. One involved itemizing expenditures by the secretary, suggesting that Herring might be "unwise and extravagant" as he had been in "statements he had made from time to time." Another amendment hoped to rein in the secretary, to put "a ban on this man... [who] canvassed openly for his own good and his own advancement." A third limited the hours that the secretary might visit institutions since Herring had appeared at "unseemly hours and demoralized patients by the use of flashlight photography." Finally, after the better part of an afternoon elapsed, the Senators cast their votes.

The bill passed 19 to 7.

|

This web site is presented for reference purposes under the doctrine of fair use. When this material is used, in whole or in part, proper citation and credit must be attributed to the Maryland State Archives. PLEASE NOTE: The site may contain material from other sources which may be under copyright. Rights assessment, and full originating source citation, is the responsibility of the user. |

© Copyright December 15, 2023 Maryland State Archives