ORGANIZING A RELIEF FAIR

![]()

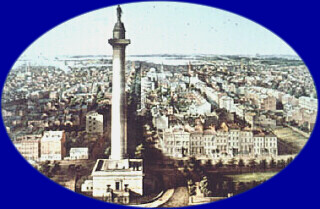

Mt. Vernon Place looking south to Baltimore harbor, c.

1860

| The 1864 Baltimore Sanitary Fair provided the

large-scale vehicle for Unionist women to bring together both benevolent

and patriotic impulses. Other cities across the Union, such as Chicago

and Boston, previously coordinated such events. Proceeds from these

affairs swelled the coffers of the U.S. Christian and the U.S. Sanitary

Commissions, the two major national relief organizations for the Union

armed forces. The prospect of holding a fair to raise funds for these

entities first arose in Baltimore during the fall of 1863. Two members

of the Ladies Union Relief Association, Ann Bowen and Fanny Turnbull, are

credited with the initial promotion of Baltimore's event. Ann

Bowen, the 36 year old recording secretary, "a South Carolinian & yet

a very strong Union Person," proposed the idea. Her spouse,

a Unitarian minister, served as chaplain of the National Hospital where

he "devote[d] all his leisure time, in fact all his time to the soldiers."

Discussing the possibility of a fair with association vice-president Fanny

Turnbull, the 41 year old Maryland-born spouse of a city dry goods merchant,

Bowen initially desired that the event proceeds be earmarked solely for

the Sanitary Commission. But, further deliberation between these

women and Harriet Hyatt, who was active in the U.S. Christian Commission's

local branch, enlarged its focus to include this latter organization.

Hyatt, 49 and a native Marylander, "a whole-souled Union lady, who ever

since the breaking out of the rebellion has given her whole efforts to

the cause of loyalty," devoted herself to relief efforts at military camps

in Baltimore as well as nearby battlefields.

A series of women's organizational meetings occurred in December 1863. Since no minutes have apparently survived, only scant details of the proceedings are available. The first meeting on December 3, "invit[ed] all Union Ladies in Baltimore" to gather at the Baltimore residence of Fanny Turnbull. Nothing is known of these initial deliberations. A second meeting took place one week later on December tenth with attendance from county women being urged. At this time, the gathered group adopted three recommendations that subsequently appeared in the Baltimore American: First, that counties and towns set up committees to define and organize local participation in the Baltimore Fair; Second, the event was to be held during Easter week 1864 (it was later determined to begin on April 19). Third, a list of items was formulated to be solicited as donations from the public for sale at the fair. Men were encouraged to assist in gathering the articles, but apparently played no active involvement in these initial organizational steps. By the December 19 third meeting, seventy-six women had banded together to shape and promote the relief fair. The constituency of the initial Fair committee appeared to be drawn primarily from white, upper middle class, merchant households of the Baltimore area. Lawyer's wives composed the second most represented group. A sample of over one-half of the women revealed their median age to be 45 years. Most were Maryland-born; however, a few came from states both north and south. Few foreign-born participated during this early stage. No African-Americans have been discerned. Numerous Unitarians, and to a lesser degree, Quakers, Episcopalians, and Methodists have been identified as organizers. The large Unitarian participation may stem from the presence of many northern emigrants within the congregation and the local church's own progressive stance regarding women's rights and duties. Only two single women appeared on the committee. E.E. Rice, age unknown, served as the president of the women's association connected with the Newton University [military] Hospital. A number of other women were similarly involved with prior soldier relief work. Elizabeth Bradford, the Governor's wife and later fair committee chair, would frequently carriage forth from her Cross Keys home to visit soldiers at Camp Tyler on Charles Street. Mary Pancoast already served as the treasurer of the Ladies Union Relief Association. Both Sarah Ball and Sarah Applegarth had nursed wounded soldiers on western Maryland battlefields. The organizers embraced both promotion and fundraising measures used by earlier Sanitary fairs. At some point in December, three women, Ann Bowen, Harriet Hyatt, and Abbey Wright attended Boston's Fair, presumably to gather both insight and ideas upon which to model Baltimore's fair. Early popular appeals sought to generate wide-spread publicity while building momentum for the women' efforts. Fair solicitations ranged from circulars to newspaper advertisements. On December 18, one day before the third organizational meeting, 20,000 circulars went out to newspapers and individuals requesting "Fancy articles . . . even 'an ironing-holder, quilted of old calico' will be acceptable to us." Notices in the Baltimore American provide evidence of neighborhood organizational appeals to fellow citizens. Both the "Loyal Ladies of North Baltimore" and the "Ladies West End Union Association" asked for "donations of money, useful, fancy or ornamental articles" for sale at the fair. The fair committee also actively sought donations of money and contributions of salable items from throughout the United States. Adams Express, a goods transfer company, generously gave free transport for all coming to Baltimore. Women did not shrink from direct written appeals. Ann Bowen wrote William Whittingham, Maryland's Episcopal Bishop and a staunch Unionist, to request six of his autographs and photographs to be raffled off at the fair. When his photos did not arrive, she asked if he could sit for his portrait and explained that "in my ardent zeal for the cause which you love so much, I dare to do at other times would simply be impertinence". Augusta Shoemaker, in a more tempered tone, addressed a Harford County businessman with the following words: "The women of Maryland, intend holding a fair . . . and I now write to ask for a contribution . . . I ought not to be surprised at an unfavorable response . . . but nevertheless think it my duty, to make every exertion in every way to further this object."

Items for sale and monetary donations soon began to flow into the fair offices. Locally, women involved in relief activities at military hospitals around Baltimore gathered to prepare items for their respective tables. "The Ladies of these societies, to the number of fifty to seventy each, meet weekly . . . at an early hour in the evening and go to work in earnest --some in cutting out clothes, silks and other goods . . . others, preparing the work, and many diligently engaged in plying the needle. "Ladies of the Baltimore County Association for State Fair" regularly published donator lists in the city newspapers. Money, but also random gifts of goods, such as cloth or china, often appeared. Harriet Archer Williams, a coordinator for the Harford County effort, received from friends and neighbors hand-made steel garden hoes, a box of hams, donations of money and foodstuffs. In addition, she sent "one box contain[ing] $47 worth of fancy articles" and three others which held "eatables for the lunch tables." Unusual items also found their place among the fair tables. J. H. Kennedy from Hagerstown, Washington County, offered "a whole parcel of little trifles made of Antietam Battlefield wood--some from the little church so famous on that terrible day." Kennedy and his wife had ministered to Union soldiers after the battle, hosting the wounded Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., in their home for several days.

Publications served as fundraising supplements to the fair effort. Almira Lincoln Phelps, the driving force behind one project, solicited short stories and poetry from noted authors and contemporary personalities throughout the Union. The persistence of the fair corresponding secretary proved quite formidable. On one occasion, when receiving a check in lieu of a manuscript, she respectfully expressed shock and remarked that "it deemed like asking for bread and receiving a stone." She politely reaffirmed her request, even suggesting a certain item from the prospective male contributor. Phelps, the 64 year old former principal of the Patapsco Female Institute, and a noted author in her own right, served as the editor of Our Country --In Its Relations To The Past, Present and Future: A National Book. This volume, dedicated "to the Mothers, Wives and Sisters of the Loyal States" contained works that celebrated the Union as well as two essays that advocated a wider domestic sphere for women. A second book, entitled Autographed Leaves of Our Country's Authors, contained facsimile reproductions of autographed manuscripts that included Lincoln's Gettysburg Address. Baltimorean John P. Kennedy, whose introduction appeared within, purchased five copies "as I may find occasion to distribute them." Even low priced pulp works were produced for additional revenue. The anonymous Incidents in Dixie detailed life in Confederate military prisons and appeared to be designed to evoke sympathy for Union prisoner of war relief efforts. Benefit performances, lectures, and other activities in Baltimore and elsewhere, helped to boost the association coffers. John T. Ford, owner of a theater bearing his name in Washington, donated the entire proceeds of one night's entertainment from his Baltimore Holliday Street location. Republican Schuyler Colfax, the then U.S. Speaker of the House, traveled to Baltimore to deliver a lecture on the "Duties of Life" with all profits going toward the State Fair effort. A "Tableaux Vivant" was scheduled for the last three nights of the fair's final week; these tableaux, depicting scenes from great historical and literary works such as "Henry the VIII," were performed by costumed members of the Fair committee with reserved seating at one dollar per person. Out in far western Maryland, Allegheny County citizens held a band concert which netted over 500 dollars for the women's effort. In Harford County, a lecture on "Books" brought an additional forty. Successful fundraising proved essential to the overall success of the fair effort. Unfortunately, the Baltimore organizers faced great competition from other cities holding similar events. The New York Metropolitan Fair partially coincided with Baltimore's while Philadelphia's gathering was slated for just weeks later in June. John H. Eccleston, a former Marylander living in Philadelphia, writing on Baltimore's chances for soliciting donations from that city, penned: "Touching the matter of subscription . . . here, for your fair --I don't think you will succeed very well; for they are getting one up [here] . . . the beggars are out in all directions, and men are buttonholed and made to listen to speeches so long, that the donations come as a sort of "ransom money" for being let go." Nevertheless, donator lists in various period publications attest to the generosity of a limited number of non-Marylanders, even Philadelphians. The Fair organizers from an early point had a guarded expectation in

the overall financial success of their event.

The second factor for the women's more conservative viewpoint resides in the perception that the fair proceed beneficiaries may not have elicited a sympathy equally from all loyal Marylanders. The financial allegiance of many Marylanders may have rested more with the localized soldier relief efforts --those geared specifically to Maryland volunteers and their family members --rather than with the seemingly impersonal, out-of-state bureaucratic agencies. Referring to the Sanitary Commission, the historian Lori Ginzberg stated "People were suspicious of an organization that seemed to absorb enormous amounts of money and still cried out for more." Perhaps reacting to current views of the Christian and Sanitary Commissions, The Baltimore American opined that the combination of ineffective workers and "occasional waste and loss" had unfairly caused "censorious persons [to] disparag[e] the efforts of these noble institutions." Yet, even the editor of the fair's own privately printed souvenir newspaper The New Era, in his closing issues, featured a lengthy column making suggestions for improving both national relief organizations. The third factor, and by far the most damning, the division of Maryland's citizens into Union and Secession factions ensured less than full participation by its populace. Several southern counties with large Secessionist populations, namely St. Mary's, Charles, Somerset, Caroline, Wicomico, and Queen Anne's, sent no official delegations. As the Eastern Shore diarist Samuel Harrison wrote, "Sentiment in this state is so divided --and so many of those who are accustomed to spend money are disloyal . . . it can not be reasonably expected that this fair should produce near as much as it would [if] this state [was] united in sentiment." Union military administrators, as well as Baltimoreans themselves, long recognized the alliance of their city's wealthy with the Confederate cause. Commenting in the summer of 1861, General John Adams Dix, believed, "The Secessionists [are] sustained by a large majority of the wealthy and aristocratic" of Baltimore. Neither years of restrictive military measures nor the ascerbic effects of war could induce re-newed loyalty. On the eve of the fair, the Clipper opined: It is not expected that the proceeds of this fair will equal those of the Northern cities . . . whose society is not thronged with enemies of the Government." Despite these lowered expectations, the fair gave loyal Maryland women their most spectacular means to express their Unionist devotion. They appeared to relish the opportunity. Channeling their energies, the women successfully mobilized thousands of fellow Marylanders, as well as sympathetic out-of-state parties, behind the cause of U.S. soldier relief. Remarkably, they achieved their organizational task in just over four months. As the April 18 opening ceremonies approached, hundreds of women converged upon Baltimore to prepare their display stands. For some fifteen days, until the closing speeches on May 2, the city witnessed a welcome diversion from the gray drudgery of war-time life. The Baltimore Sanitary Fair brought color, pomp and gaiety to city streets while providing yet another occasion to express Maryland's Unionist patriotism. |