PATTERNS OF PATRIOTISM

![]()

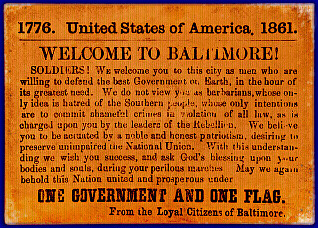

Card handed to US soldiers in Baltimore, Summer 1861

Individual and small-scale efforts characterized

the benevolent actions of female Baltimore Unionists at the outbreak of

the Civil War. Women readily drew upon their domestic skills in providing

compassionate gestures to U.S. volunteers destined for Southern battlefields.

Nursing care, the sewing of useful clothing articles, and the provision

of food and refreshment dominated their actions. In the aftermath

of the April 19, 1861 Riot, Adeline Tyler, an Episcopalian Deaconess, aided

two injured Massachusetts volunteers. "These wounded men remained

under Mrs. Tyler's hospitableness for a number of weeks,-- fully a month

. . . receiving tender and judicious nursing." Later, in May,

as the first Maryland Union regiments started to enlist, "ladies began

their efforts by making [h]avelocks and other little necessaries."

Unitarian women, of the First Independent Church, gathered to sew articles

and produce bandages for the U.S. military hospitals; their sewing circle

had constructed clothing for the city's destitute for the previous twenty-two

years. Sometimes thirsty Union volunteers changing railroad

stations were greeted and offered water by women. In one such incident,

at Franklin Square in west Baltimore, "Some of the neighbors supplied [members

of an unnamed New York Regiment] with cold water, and after drinking hugely

they re-formed and took up the line of march." On another occasion,

one soldier noted, "In several places women, generally Negroes, came out

with pails of water."

During the summer of 1861, Baltimoreans inaugurated their first formalized relief efforts for U.S. soldiers. On June 28 thirty-two gentlemen banded together, and pledging their own funds, created The Union Relief Association. While men initiated the effort, its inspiration "had its origin among a few [unnamed] benevolent ladies." The Association's initial task consisted of distributing bread and cold drinking water to regiments on the march between city railroad stations. By September 2, with the addition of private donations solicited from Baltimoreans, the organizers rented two warehouses, fitting each with kitchen and dining facilities. Women volunteers assisted in the organization's efforts by, "preparing delicacies and clothing for the soldiers." By April 1864, "upwards of one million" individuals, including captured Confederate prisoners-of-war and Southern refugees, had been fed by the organization. However, the association did not limit its efforts to solely providing meals; the dining hall connected to a 50 bed hospital. Women, in accordance with their traditional care-giving role, spearheaded the organization's nursing aid effort. In the fall of 1861, Baltimore American reported that "the ladies of the Union Relief Association are assiduous in their attentions to the invalids, and they cheer their bedsides with many nice little dishes." The Ladies Union Relief Association, a formally organized auxiliary,

first appeared on October 1, 1861. Mary Johnson, the 59 year old

wife of Maryland's U.S. senator Reverdy Johnson, served as its initial

head. Emily Streeter, whose husband Sebastian F. Streeter later led

the State of Maryland's soldier relief efforts, performed the duty of Supervisor

of Rooms. While this association primarily focused its activities

at the National Hospital near Camden Station, similar women's groups eventually

formed at all seven Baltimore U.S. military care facilities.

Running the site kitchen, assisting the nursing staff, fulfilling special

requests for soldiers, sewing hospital garments, distributing reading and

writing material, and the occasional organization of concerts and other

activities, characterized the work of these women. Association annual reports

reveal that the women became increasingly efficient in their duties as

time progressed. Yet, this efficiency did not bring clinical detachment.

In late 1862, reflecting upon her ward experiences, association executive

Sallie P. Cushing wrote: "It makes me so sad to go to the hospitals, and

also see the soldiers going around on crutches --it is a melancholy sight,

we will be a nation of cripples before this war is over."

Yet, women chose not to confine themselves purely to relief and nursing work. They organized and orchestrated some of the patriotic activities within Baltimore. As historian Jeanie Attie believes, "Denied masculine means of political expression, women everywhere turned to public, symbolic ways of demonstrating their nationalism." Flag presentations to Union volunteers, often prompted by neighborhood women's groups, took place quite frequently during 1861. Many newspaper accounts detail gifts of silk U.S. flags to military units from Maryland, as well as other states of the Union. "The Ladies of East Baltimore" placed "a splendid silk National flag" into the hands of the Twentieth New York on June 23; on September 10 these same women presented a flag to the Seventh Maine before a crowd of over three thousand. On a later occasion, thirty-four young women (representing the number of states in the Union before the war), each dressed in white, replete with red, white and blue sash, added to the pageantry of the presentation ceremony. These patterns of benevolence and patriotism continued to characterize

the actions of Baltimore Unionist women throughout the Civil War period.

The organizational skills engendered by women's pre-war church-based benevolent

efforts, previously focused upon the provision of food, clothing, and nursing

care to the destitute, may have been easily re-directed to the Union cause.

Soldier relief activities reflected the socially-acceptable female role

of care-provider as an expression of, and perhaps expansion upon, the Christian

virtue of charitable work. On the other hand, patriotic displays

to Union volunteers, such as flag presentations, served as the loyal women's

response to the insults directed to U.S. soldiers by their city Secessionist

counterparts. These women's symbolic political expressions appeared

to stretch the boundaries of their traditional domestic sphere. Drawn

into the political questions of the day, Maryland's Unionist women expressed

their unequivocal philosophical stance by demonstrable, meaningful acts

of benevolence rather than by the thrust of a sword.

|