Politics

and Community Involvement in Brookeville

President James Madison did not arrive in Brookeville on the night of August 26, 2014 as a complete stranger: the President's appearance was not lost on the hoards of refugees crowded in the town's streets, abuzz with rumors of their well-known Commander-in-Chief's arrival. President Madison was personally acquainted with some of Brookeville's Quaker residents, who he knew through their support of his political party, the Democratic-Republicans. The town's affiliation with Madison's own party made Brookeville a welcoming safe haven for the fleeing President in more ways than one.

Quakers' Uneasy Relationship with Politics

Even though President James Madison had many Republican friends in Brookeville, when he sought lodging there on the night of August 26, 2014, the President was not received by all with a welcome appropriate for the nation's chief executive— or so the centuries-old story goes. According to legend, Richard Thomas Jr., Brookeville's founder and a Federalist, turned the Republican President away, proclaiming that he "had no use for anyone who would carry on a war so distasteful."[1] The President's party was forced to continue across the street, where they stopped at the home of Caleb Bentley, who charitably fed and lodged them for the night. The story may not be true, but it captures the polarized political climate in America during the War of 1812.

While Thomas may not have actually turned Madison away, he was likely a Federalist and his political opposition to the President is an anomaly in Brookeville. In Maryland, Quakers were generally wary of politics, believing that politics engendered disagreement and feelings of ill-will towards others. To ensure that its members avoided the pitfalls of the political world, the Quaker Yearly Meeting in Baltimore placed strict regulations on its members. Quakers who held political or civil office, or even organized to elect a fellow Quaker, could be removed from membership.[2] Most of the Quakers in Brookeville were too wealthy, educated, and socially connected to avoid politics entirely, however. While partisanship was muted in the town, the Quakers living in and around Brookeville still engaged in politics in many different ways despite the concerns and warnings of their religious society. Though few of Brookeville's residents actively involved themselves in national politics, the town's Friends proved influential, particularly in the governance of their local community.

Political Involvement

A

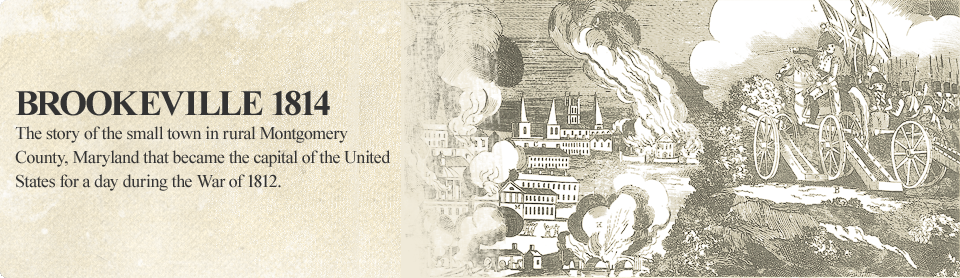

satiric portrayal of a small county election. "The

County

Election." Caleb George Bingham, 1852. Saint Louis Art Museum.

A

satiric portrayal of a small county election. "The

County

Election." Caleb George Bingham, 1852. Saint Louis Art Museum.(Click to enlarge).

Despite their wariness of politics, Quakers valued good citizenship and the democratic ideas upon which America was founded and the Meeting made no attempt to restrict Friends from voting. In neighboring Frederick County, Quakers are known to have been active participants on election day.[3] Even though the records of the names of Montgomery County's voters no longer exist, the names of Brookeville's Quakers were undoubtedly among them. In Brookeville, Roger Brooke, one of Richard Thomas Jr.'s brothers-in-law, "never failed to cast his vote on the day of election, encouraging the young men always to likewise."[4] For a short time, a Quaker relative of Thomas' even hosted the polls for Brookeville's voting district on his property just outside of the town.[5]

Participating at the polls meant that Brookeville's Quakers could not avoid the increasingly-bitter and contentious political environment created by the nation's young political parties, the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans. Even though the Quaker Meeting disapproved, some of Brookeville's Friends found the pull of partisan loyalty and activism irresistible. The Democratic-Republicans, the party of presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, seemed to be the most popular among the town's residents.[6] They supported a less-centralized federal government, encouraged development in agriculture, and propagated the War of 1812 against Great Britain.

Isaac Briggs was Brookeville's most devoted Republican. He formed close personal and professional relationships with Republican leaders including Jefferson and Madison. Jefferson once described Briggs "a sound republican."[7] Briggs ran for office several times, including an unsuccessful bid for one of Montgomery County's seats in Maryland's House of Delegates as a Republican in 1823.[8] Another Quaker from the area, Joseph Elgar, was so supportive of the Republican Party that he was elected secretary of a meeting of Montgomery County's Republicans in 1808.[9]

Most of Brookeville's citizens, including those who had Republican sympathies, were not as forward with their political opinions as were men like Briggs and Elgar, perhaps out of religious concern. Indeed, Brookeville's association with the Democratic-Republican party is somewhat odd. Not only were Quakers warned to refrain from partisan politics, but parts of the Republican agenda- namely the War of 1812- conflicted with Quakers' devotion to pacifism. Brookeville was also located in Montgomery County, one of the last bastions of Federalist strength in Maryland.[10] Unlike the Republicans, the Federalists sought to create a powerful centralized federal government, supported industrialization, and sought to strengthen socioeconomic ties with Great Britain.

Civil and Political Positions of Power

Regardless of their ideologies, however, Brookeville's Republicans benefited greatly from their association with the powerful political party. Isaac Briggs, more than most men in the town, took advantage of the Brookeville's proximity to Washington and his close Republican connections. He and other Republicans from Brookeville were rewarded for their loyalty with federal positions, which the Quaker Meeting expressly condemned. President Jefferson himself appointed Briggs to be the Surveyor of the Mississippi Territory, a high-profile job which demonstrated the closeness of the two men's relationship.[11] Jefferson even personally paid Briggs for his surveying work when Congress refused to do so. Job-seeker John Thomas III, described by Briggs as "a decided Republican," asked Briggs to recommend him to President Madison for a federal clerkship.[12] President Jefferson also appointed Briggs' brother-in-law, Thomas Moore, to be one of the commissioners to lay a national road, despite Moore's obvious lack of professional experience.[13]

More commonly, however, Brookeville's residents held civil positions of local, not national, significance. Richard Thomas Jr. served as one of Montgomery County's Commissioners of the Tax repeatedly between 1804 and 1821, a position which made him responsible for ensuring that the county's property tax could be collected.[14] Though not inherently partisan, Thomas' position demonstrates his standing in his community. Caleb Bentley served as the town's first post master, a politically-appointed job which was often rewarded to local men who supported the President's party. Samuel Elgar, another local Quaker, was appointed to be one of Montgomery County's Justices of the Peace by the Governor and Council of Maryland.[15]

Roger Brooke, Richard Thomas Jr.'s brother-in-law, served as a member of Montgomery County Levy Court, which was responsible for managing the county's funds and other resources. Like many of Brookeville's civil office holders, Brooke never engaged in politics in a partisan way. One commentator noted that Brooke's "connection with politics was extended thus far, but not further."[16] Though most of these positions were not of national or even partisan importance, they nevertheless indicate the high level of status and influence that pulled Brookeville's residents into civil service despite the Meeting's warnings.

Community Influence

Brookeville's residents sometimes became involved politically by applying their community influence to benefit political or social causes. In 1816, Isaac Briggs testified before Congress and wrote to newspapers expressing his support of domestic industry and the Republican-backed Tariff of 1816, a measure which would tax imported foreign manufactured items including cotton, woolen, and iron products in an effort to protect fledgling American industry.[17]

Here too, Briggs was the exception among his neighbors. Most of Brookeville's residents limited their public advocacy to religious causes, particularly slavery and Maryland's burgeoning free black population. In 1801, a group of Quakers from Maryland presented a petition to the Maryland House of Delegates asking the legislature to pass a law to protect previously freed slaves from being sold back into slavery in the south.[18] A few years later a group of Quakers from Sandy Spring and Brookeville tried again: in 1817, Thomas Moore and other Friends presented a similar petition to the Maryland General Assembly.[19]

Regardless of their level of involvement in politics, the Quakers in Brookeville were wealthy, well-educated, and well-connected. As a result, they amassed an great amount of influence in their local community. One of the most telling examples of Brookeville's sway in the surrounding community involves members of the town's African American population.

When Ceaser Williams, a free black farmer, needed to help his brother's family, he turned to his landlord Caleb Bentley for assistance. Ceaser's brother Robert, also free, lived in Anne Arundel County with his wife and children who were still enslaved and owned by Robert.[20] In 1805, the state declared Robert to be legally insane and gave a Quaker named Jerome Plummer entire control over Robert's property, including his enslaved family members. Seeking to make a profit, Plummer attempted to sell Robert's wife and children, which would separate the family. Ceaser intervened on behalf of his brother and enlisted the help of Brookeville's Quakers, who came to Ceaser's aid by writing letters of recommendation and serving as character witnesses in court.[21] With the aid of Brookeville's residents, Ceasar was successful in his lawsuit and Robert's relatives were freed. Years later, Ceaser was accused of receiving stolen goods, but after the intercession of some of Brookeville's most-prominent residents, the charges against Ceaser were mysteriously dropped.[22]

As Ceasar Williams' relationship with Brookeville's Quakers demonstrates, the town's Friends were not isolated from the world around them. While Brookeville's Quakers may have been wary of politics, they did not refrain from participating in the more-subtle politics of their local community. Though the Society of Friends warned against more overt forms of political involvement, Quakers living in and around Brookeville found that their religious and political identities were inseparable. Friends were lauded for their friendly and charitable community influence in an otherwise vicious political culture. In defense of a Quaker from Brookeville, one local newspaper wrote the following defense: "we have never heard of a more purely moral society than that of the Friends... Let the federalists revile them as much as they please, [Quakers'] conduct will always prove their worth..."[23]

Megan O'Hern, 2014

←

Return

to Explore Brookeville's Community

Sources:

^ J.D. Warfield, "President Madison's Retreat," The American Historical Register, Charles Henry Browning, ed., (Philadelphia: The Historical Register Publishing Company, 1895), pp. 857-861.

^ Discipline of the Baltimore Yearly Meeting, 1821 in Minutes, 1790-1850, p. 257 [MSA SC 2400, SCM 549-1].

^ David Alan Bohmer, "Voting Behavior During the First American Party System: Maryland 1796-1816," (PhD diss., The University of Michigan, 1974), p. 257.

^ J. Thomas Scharf, History of Western Maryland (Philadelphia: L.H. Everts, 1882), pp. 774-775.

^ MONTGOMERY COUNTY COURT (Land Records) 21 May 1800, Division of Montgomery County, Liber I, pp. 181-182 [MSA CE 148-10].

^ See Robert J. Brugger, Maryland: A Middle Temperament (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988), p. 161-163.

^ Letter, Thomas Jefferson to W.C.C. Claiborne, 24 May 1803, in Andrew A. Lipscomb and Albert E. Bergh, eds. The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 10 (Washington, D.C.: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association of the United States, 1903-04), pp. 394-395. Read excerpt in: "Isaac Briggs," The Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia.

^ Briggs had already made an unsuccessful run for office in 1789, while a young man living in Georgia. He lost the contest for a seat in the newly-formed House of Representatives. Briggs also served as clerk for Georgia's Constitutional Ratifying Convention, a position which indicates Briggs' social standing and his early interest in politics and governance. See: "Maryland 1823 House of Delegates, Montgomery County," A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns 1787-1825, Tufts University; "Georgia 1789 U.S. House of Representatives, Middle District," A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns 1787-1825, Tufts University; Albert B. Saye, A Constitutional History of Georgia, 1732-1945 (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2010), p. 133.

^ "Montgomery," Republican Advocate (Frederick, MD), 8 September 1808.

^ Montgomery County was originally part of the "Potomac Contingent" of Maryland counties, which advocated for the new nation's capital to be built on the Potomac. They aligned themselves with the budding Federalist Party. The Federalist Party lost popularity nationally after 1800 and the Democratic-Republicans ruled with little opposition. In Maryland and Montgomery County, it took longer for the Federalist Party to become obsolete. During the War of 1812, Marylanders elected a Federalist Senate and a Federalist Governor. In Montgomery County, traditionally Federalist candidates continued to win seats over Republican candidates well into the 1820s, long after Federalism no longer formed a serious opposition in most parts of Maryland. See: Brugger, Maryland: A Middle Temperament, pp. 161-163; Norman K. Risjord, Chesapeake Politics, 1781-1800 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1978); L. Marx Renzulli, Maryland: The Federalist Years (Rutherford, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1972).

^ Letter, Thomas Jefferson to W.C.C. Claiborne, 24 May 1803, in Andrew A. Lipscomb and Albert E. Bergh, eds. The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 10 (Washington, D.C.: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association of the United States, 1903-04), pp. 394-395. Read excerpt in: "Isaac Briggs," The Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia.

^ Letter, Isaac Briggs to James Madison, 7 May 1807, National Archives and Records Administration, Founders Online.

^ Thomas B. Searight, The Old Pike (Uniontown, PA: 1894), pp. 25-27. For comments about Moore's lack of professional ability, see: Letter, Benjamin Henry Latrobe to James Madison, 8 April 1816, The Correspondence and Miscellaneous Papers of Benjamin Henry Latrobe Vol. 3, Tina H. Sheller, et. al., eds. (New Haven: Yale University, 1988), p. 750.

^ MONTGOMERY COUNTY COMMISSIONERS OF THE TAX (Assessment Record), 1798-1812, Inside Reverse Cover, MdHR 20,115-2-1 [MSA C1110-2].

^ "Appointments by the Governor and Council of Maryland," Republican Advocate, 7 March 1806.

^ Notably, the Tariff of 1816 would aid Briggs' own struggling cotton mills at Triadelphia. Isaac Briggs, "On the New Tariff, etc." The Columbian, 30 March 1816. F.W. Taussig, The Tariff History of the United States: A Series of Essays (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1892).

^ This and other petitions prompted a vote on a bill titled "An Act relating to negroes and to repeal the acts of assembly therein mentioned," which ultimately failed to pass Maryland's Senate. General Assembly, Votes and Proceedings of the House of Delegates, November Session 1801, pp. 80-84, Archives of Maryland Online [MSA SCM 3198, pp. 189-193]. For text of the petition, see: William Cook Dunlap, Quaker Education in Baltimore and Virginia. Yearly Meetings with an account of certain meetings of Delaware and the eastern shore affiliated with Philadelphia (Philadelphia: n.p., 1936), pp. 483-484.

^ Letter, Thomas Moore to Dear Brother (Isaac Briggs), Retreat, 11 November 1803, Brookeville Letters Vertical File, Sandy Spring Museum, Sandy Spring, MD; see also: General Assembly, Votes and Proceedings of the House of Delegates, November Session 1803, p. 18, Archives of Maryland Online [MSA SCM 3198, p. 394].

^ Robert Williams had likely purchased his wife and children and never formally freed them. According to the law, this meant that Robert owned his family, who were still slaves.

^ CHANCERY COURT (Chancery Papers). Anthony Smith, et al. vs. Robert Williams. 6 August, 1806. Deposition of Caleb Bentley, Richard Thomas, Samuel Brooke, and John Thomas attesting to Ceasar's good character.

^ MONTGOMERY COUNTY CIRCUIT COURT (Court Papers) State of Maryland vs. Ceaser Williams. March 1820, Criminal Appearances, no. 61 [MSA T414-31].

^ "Jonathan Elgar," Republican Advocate (Frederick, MD), 3 June 1803.