Triadelphia: Brookeville's

Failed Cotton

Experiment

As the British burned the public buildings of Washington, D.C. in August of 1814, President Madison experienced one of the lowest points in his tenure as Chief Executive. The President arrived at Brookeville exhausted from his travels, unsure about the capital city's fate, and weary from war. But while the President fervently wished for a successful end to the war, for many domestic industries the end of war meant financial ruin as British goods would once again compete with American ones. The peace that came in 1815 took its toll on a number of Brookeville's industries, including the fledgling cotton yarn manufactory at Triadelphia. Soon after, the factory's founders would give up the struggling factory complex, which would never be able to regain the promise it once had before the war.

Cotton Mania

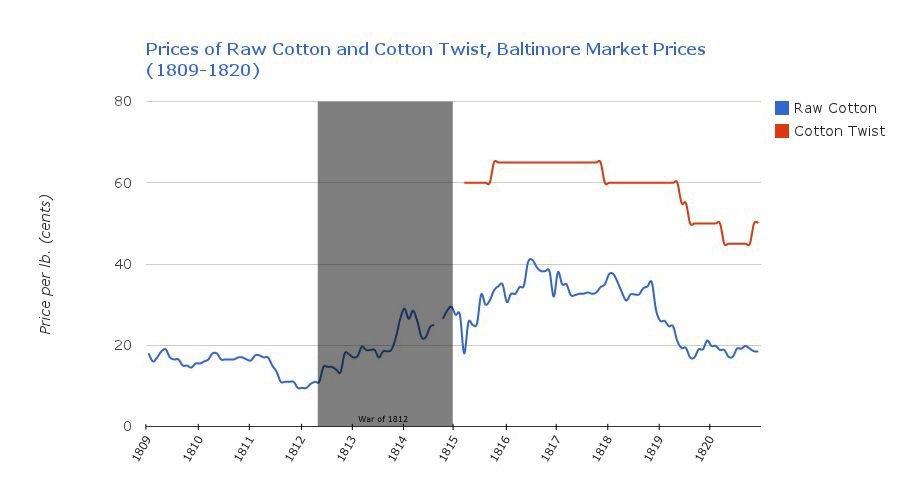

The cotton mania started in 1808. By that year, the United States' Embargo of 1807 had cut off all trade with England and France in response to years of attacks on American shipping. The price of raw cotton fell as British demand for American cotton ceased entirely as a result of the embargo.[1] At the same time, American demand for finished cotton products, like cotton yarn, soared with the complete disappearance of imported British goods. Because the cost of raw cotton was so low and the price of cotton yarn remained high, producers of cotton yarn (or "twist") expected to make great profits.[2]

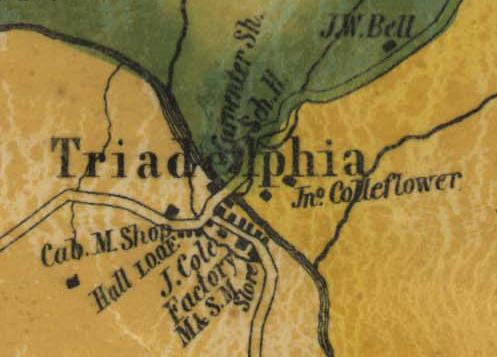

To outside observers like Isaac Briggs, Brookeville's enthusiastic entrepreneur, the cotton yarn market seemed like a profitable environment. In 1809, in hopes of capitalizing on this seemingly-favorable profit margin, Briggs convinced two of his brothers-in-law "after many earnest efforts," to provide the capital to found a cotton yarn factory on the shore of the Patuxent River, just three miles outside of Brookeville.[3] Briggs and his financiers, Caleb Bentley and Thomas Moore, named their new factory and town Triadelphia, though the company was known locally as "Caleb Bentley & Co.," a nod to the man who contributed over half of the capital used to start up the factory.[4]

These Brookeville men were not the only eager industrialists attempting to turn a profit in the cotton yarn industry. Despite the depressed economy which followed the Embargo of 1807, the total number of new cotton twist factories boomed. In 1808, only fifteen mills across the country spun cotton. By the end of 1809, eighty-seven cotton mills, including Triadelphia, were beginning to produce cotton yarn.[5] But the low cost of raw cotton and the high price of finished cotton yarn made the business seem more lucrative than it truly was. Many Americans couldn't afford the expensive cotton yarn and the industry suffered. New England yarn manufacturers, already suffering from low sales by 1808, looked on in dismay as new mills were founded in increasing frequency: "the business of cotton spinning looks likely to be very much overdone."[6] This somber prediction turned out to be all too true for Brookeville's manufacturers who saw their Triadelphia venture begin to fail only six short years after its establishment.

The price of domestic cotton was low in 1810 when Triadelphia began manufacturing cotton yarn, allowing the company to be profitable. The cost of American cotton rose drastically during the War of 1812 as the American textile industry boomed to fill the gap left by the cessation of trade with the British. Cotton prices reached an all-time high after the war. Already struggling with low sales, Triadelphia could not make a profit when raw cotton prices were so high and the venture began to fail around 1816. Its troubles were compounded by the Panic of 1819, which devastated the American economy and caused both the cost of cotton and yarn to fall. Price data is collected from The Baltimore Price-Current. During the British attack on Baltimore in September, 1814, the city's harbor was blockaded, preventing the importation of goods and preventing the newspaper from publishing its price reports (resulting in the gap seen on the graph).

Triadelphia's Founding

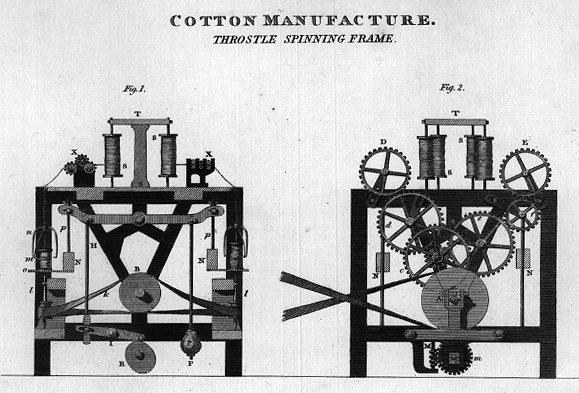

Briggs and his partners had great hope for success at the start of the venture. In 1809, the men began building on the vast "wilderness" which would become home to Triadelphia's factory and town.[7] By January of 1810, the company was ready to begin producing cotton yarn. The factory building itself was three stories high and "substantially built of stone."[8] Though it was originally stocked with only 156 spindles (a wooden rod necessary for spinning cotton and used as a measure for each factory's capacity and output), the factory building had space to accommodate 1,200 spindles. Briggs predicted that the abundant land and water power from the Patuxent River would allow for 5,000 spindles to be installed in various mills to be built at Triadelphia.[9]

A small town "with quite a large tenantry" quickly grew around the factory. Briggs and his partners installed a farm, grist and saw mills, a store, a post office, and a number of houses to accommodate the town's residents and the factory's workers.[10] In addition to a male (and usually Quaker) superintendent to oversee the factory's day-to-day operations, the company employed "chiefly little girls, as were found in the neighbourhood, who had never in their lives seen a thread drawn this way."[11] Other nearby residents were hired to haul raw cotton from Baltimore to Triadelphia and the finished yarn to sellers across the state. Briggs played the largest role of all the founders in running Triadelphia, he wrote: "The establishment was conducted and managed by me, for no other compensation than a share of the profits."[12]

Side view of throstle spinning frames, one type of spindle used at Triadelphia, 1813. Abraham Rees, The Cyclopedia; Or , Universal Directory of Arts, Sciences, and Literature, vol. 2., 1820.

A Busy Town Emerges

In 1810, the apparent health of the cotton yarn market suggested future success for Triadelphia. The price of raw cotton was not rising as quickly as inflation and the cost of finished cotton twist was not falling, allowing for greater profit margins. Over the course of the War of 1812, Americans sought domestically-manufactured products and British competition in the yarn industry was eliminated. Fueled by this friendly economy, Caleb Bentley & Co. grew. The operation's total number of spindles rose from 196 to 300 between 1810 and 1812. And by 1814, Triadelphia operated 500 spindles. In 1820, though only 444 spindles were operating, over 900 had been installed in the factory building.

Isaac Briggs' grandson, Granville Sharpe Bentley, lived at Triadelphia as a child and recalled in his old age: "This was a thrifty and busy place at this time. You could hear the hum of machinery from morning until night and all branches of the business seemed to move like clockwork and perfect system seemed to pervade every department. All appeared to be industrous [sic.] and happy..."[13] Briggs looked upon the factory's progress and dreamt of a day when the company could operate at its fullest potential. He even made extensive plans to expand Triadelphia's operations to include processing and spinning wool.[14] In 1812, less than two years after beginning operations, Briggs wrote to President James Madison from Triadelphia: "I have been 20 months engaged in spinning cotton. The experiment is encouraging."[15]

A Venture Set Up For Failure

Despite Briggs' initial confidence, the Triadelphia venture was fatally flawed. For a number of reasons, the Quakers' factory could not compete suitably with other Maryland cotton mills. To begin with, Triadelphia incurred costs that other factories avoided. Because Maryland's climate was too cold to grow cotton, Caleb Bentley & Co., like all cotton mills in , had to purchase imported cotton which arrived in the Port of Baltimore from the country's southern states. Triadelphia's partners bought cotton on commission and likely had to hire a man to haul their purchase from Baltimore to Triadelphia, about twenty-five miles of poorly-paved roads away.[16] Montgomery County was too far from Baltimore compared with most of the state's other cotton mills, many of which were located just outside the city on the Jones Falls. Triadelphia's competitors were not saddled with the same high transportation costs.

Additionally, most of the region's cotton mills were significantly larger than Triadelphia, which in 1820 only used 444 out of its 924 installed spindles. In the same year, the Union Manufacturing Company near Ellicott City, operated with 4,000 spindles. The Powhatan Company in Baltimore, required 5,300 spindles, the Patapsco Manufactory, also near Ellicott City, had 3,500 spindles, and the Washington Company, only six miles north of Baltimore, had 1,600. While under-usage of spindles was not uncommon for many cotton mills in the area, Triadelphia always operated on a smaller scale than all of the region's other cotton mills and produced fewer goods.[17]

Thomas Lansdale's House (right) and a partitioned "double-house" that would have housed two employees and their families. Delos H. Smith, 1936. Historic American Buildings Survey. Library of Congress.More problematic than its small size and reduced output, Triadelphia's operations were not as diverse as its competitors. The only product that Caleb Bentley & Co. produced was cotton yarn. Companies like the large Union Manufactory supplemented their income by weaving some of the yarn they produced into cloth which could be sold for an even greater profit. All of Triadelphia's main competitors diversified their production by producing cloth or cleaning and spinning wool. By 1823, advertisements selling the Triadelphia mill highlighted the company's recognition of their important production shortcoming: one advertisement included "ten new power looms" among the factory's assets. But diversification alone would not be enough to save Triadelphia.[18]

The company's sales also lagged behind those of their competition. Triadelphia sold their cotton yarn at a higher price than the mills around Baltimore and Ellicott City, which sold their yarn for roughly ten percent cheaper.[19] While larger and closer companies had dominion over Baltimore's local and export markets, Triadelphia sold its goods to towns on the periphery of the state. Caleb Bentley & Co. sold most of its yarn on commission to local vendors at Frederick, Georgetown, and Rockville. Triadelphia made most of its profit, however, in sales made to smaller Quaker towns like New Market (near Frederick, Waterford (in Virginia), and Brookeville.[20] Triadelphia may have relied upon these Quaker connections to keep their business afloat, but rural Quaker-led towns could not provide enough demand to energize the company's sales.

By 1814, when Triadelphia was at the height of its operations, the situation was not promising. Though the factory was making a profit, it was very small as a result of many of the weaknesses discussed above. In the first sixth months of 1814 alone, the combined profits of the yarn factory, grist mill, saw mill, farm, and rents was a meager $1,493. These profits paled in comparison with Triadelphia's total debt of over $34,000.[21]

Outside Forces Take Their Toll

The arrival of a harsher economy at the end of the War of 1812 made success even more elusive for Triadelphia. The Treaty of Ghent ended the war in 1815, just two and half years after it had begun. With the end of the war, trade with Britain re-opened and British cotton products flooded the American market. Raw cotton prices, which had been steadily rising since the beginning of the war, reached an all-time high in the summer of 1816. The textile and cotton yarn industries suffered further as a result of increased British competition, prompting the passage of the protectionist Tariff of 1816.[22] The cotton industry was in danger and may have failed if not for the measures of the Tariff of 1816, which raised duties on cotton imports from England to as high as 25 percent.[23] Despite measures like the Tariff of 1816, in the year immediately after 1815, Caleb Bentley & Co. was in distress. For Triadelphia, government protection was not enough to stem the effect of increasing competition, both foreign and domestic. The men who founded Triadelphia weren't alone in the misfortune brought by the end of the war. The favorable economic situation prior to the War of 1812 prompted David Newlin to found a textile mill just outside of Brookeville. But as with the Triadelphia venture, the end of the war and the resulting economic competition with Great Britain ruined Newlin's business as well.

Detail of a map containing the town of Triadelphia in c. 1860. "Map of Howard County, Maryland." Simon J. Martenet, 1860. MSA SC 5339-17-3.Triadelphia's economic woes were compounded when, around 1815, Isaac Briggs left the company for more favorable circumstances. Triadelphia had not been able to compensate him for his work by the end of 1814 and his arrest for over $9,000 in unpaid debts to the United States government forced him out of business.[24] He retreated to Delaware where he found employment as a superintendent of the Thomas Little & Co. cotton mill for a few short years.[25] Brookeville resident Thomas Moore was left to carry on business at the failing mill. After Briggs' departure, Moore wrote repeatedly of Triadelphia's troubles: "a great proportion of the Triadelphia Business and of the concern at Brookeville have fallen to my lot. Those are both bad concerns and have given me a great deal of trouble."[26]

In 1817, a great "freshet," or flood, complicated the company's problems. Moore described the damage to Isaac Briggs: "Thee wilt have some idea of our sufferings when I tell thee the water was seven feet three inches deep on our carding room floor. The shop near the Grist Mill was taken away with its contents, and several other small buildings..."[27] By 1818, Moore's reports continued in their gloominess: "the Cotton business remaining with us is a very poor one..."[28] The ensuing nationwide Panic of 1819 depressed the country's economy, further encouraging Triadelphia's difficulties.

The factory could not hide its suffering by 1820. When asked to report on their business operations for the census, Caleb Bentley & Co. responded that "the profits as shown... [are] much too small for the capital employed and has not been better for the last 4 years."[29] When Thomas Moore died in 1822, Caleb Bentley and the remaining partners attempted to sell their under-performing business. The advertisements placed in the newspaper, however, were never satisfactorily answered. By Isaac Briggs' death in 1825, the factory had still not been sold. With Triadelphia's two largest investors gone, Bentley and the company's stockholders tried to sell the factory a second time, "on very accommodating terms."[30] Their efforts were futile once again. Instead of selling Triadelphia, the partners leased it to fellow Quaker Samuel P. Gilpin. Cotton yarn was no longer as attractive and promising as it had been in 1809.

A Town Lost to History

The Triadelphia Reservoir today.

Samuel P. Gilpin eventually purchased Triadelphia when his lease ended in 1830, but a new owner did not end Triadelphia's troubles. Gilpin became entrenched in debt and fled the country. The establishment was sold to another Quaker, Edward Painter, who also failed at turning the factory into a profit-bearing institution. When Painter could not pay his mortgage payments, the factory was sold a final time to Thomas Lansdale. Lansdale's ownership of the factory meant an end to Quaker control over the business, signified by a new name: the Montgomery Company. Lansdale managed to keep the company running despite all of its troubles, but even so "it was never successful."[31] After Lansdale's death in 1879, the Montgomery Company could not repay the debt of $22,008 that it owed him in wages and unpaid loans.[32]

In its later years, Triadelphia was challenged by more bad luck and natural disasters. A fire in 1843 destroyed the entire factory and left one hundred employees without work.[33] Another fire in 1860 destroyed buildings owned by the factory and Thomas Lansdale's own house.[34] Devastating floods came again in 1847, 1868, and 1889.[35] The damage caused to the factory by the third flood "amount[ed] to a wreck." Thomas Lansdale and his family were forced to "wad[e] in water waist deep to make their escape..."[36] Though that flood ended the mill's operations at Triadelphia, local residents continued living in the remains of the same factory town that their parents and grandparents had helped found, until 1942 when the town's residents were evicted, its buildings were knocked down, and the calm valley was intentionally flooded with water from the Patuxent River. The reservoir which today sits atop Triadelphia's remains, beautiful and peaceful in its own right, covers up a special history, not only of America's Early Republic, but of a dynamic and persistent community.

Sources:

^ Imports of U.S. cotton into Liverpool, for example, fell from 143,756 bags in 1807 to only 25,426 bags in 1808. See G.W. Daniels, "American Cotton Trade with Liverpool Under the Embargo and Non-Intercourse Acts," The American Historical Review 21, no. 2 (1916), 278.

^ Caroline F. Ware, "The Effect of the American Embargo, 1807-1809, on the New England Cotton Industry," Quarterly Journal of Economics 40, no. 4 (1926).

^ Letter, Isaac Briggs to Thomas Jefferson, 16 February 1816, Library of Congress, The Thomas Jefferson Papers.

^ Triadelphia is derived from a Greek word meaning "Three Brothers," likely in reference to the familial relationship between Briggs, Bentley, and Moore. Caleb Bentley originally purchased seven of the total twelve shares. Thomas Moore owned four shares and Bernard Gilpin owned one.

^ Albert Gallatin, "Manufactures, April 19, 1810," American State Papers, Finance, II (1832), 427-428.

^ Almy & Brown to J. Pope, 23 December 1808, quoted in Ware, 681.

^ Isaac Briggs' Notebook, Vol. 4, "A Statement of facts," Briggs-Stabler Papers, MS 147, Maryland Historical Society, c. 1814-1815.

^ "Triadelphia Cotton Factory for Sale," Daily National Intelligencer, 21 December 1823.

^ Isaac Briggs' Notebook, Vol. 4, "A Statement of facts," Briggs-Stabler Papers.

^ Letter, G.S. Bentley to Dear Cousins E. and F., Green Hill, Ohio, 18 April 1889, Sandy Spring Museum, Sandy Spring, Maryland.

^ Isaac Briggs' Notebook, Vol. 4, "A Statement of facts," Briggs-Stabler Papers.

^ Letter, Isaac Briggs to Thomas Jefferson, 16 February 1816, Library of Congress, The Thomas Jefferson Papers.

^ Letter, G.S. Bentley to Dear Cousins E. and F., Green Hill, Ohio, 18 April 1889, Sandy Spring Museum.

^ Isaac Briggs' Notebook, Vol. 6, "Proposal for a limited partnership," Briggs-Stabler Papers, MS 147, Maryland Historical Society, c. 1815-1817.

^ Letter, Isaac Briggs to James Madison, Triadelphia, 16 May 1812, "Founders Online," National Archives and Records Administration.

^ The two most common types of cotton coming into the Port of Baltimore were Sea Island cotton (from the Carolinas) and Georgia Upland cotton. See the Baltimore Price-Current, newspaper, Baltimore, MD.

^ Fourth Census of the United States, 1820, Manufactures. This data has been collected by John McGrain and can be found listed among Baltimore County mills in "History of Molinography" [MSA SC 4300-5]. Note that the Patapsco Company is listed under Grays Cotton Manufactory.

^ "Triadelphia Cotton Factory For Sale," Daily National Intelligencer, 21 December 1822.

^ Isaac Briggs' Notebook, Vol. 5, "Union Factory Wholesale Prices," Briggs-Stabler Papers, MS 147, Maryland Historical Society, c. 1812.

^ Twenty-seven percent of sales in the latter half of 1812 were made at Waterford. Twenty-one percent of sales were made at Brookeville. Though Frederick and Washington were large markets, they only accounted for the smallest proportion of sales at Triadelphia in 1812. Unfortunately, Briggs' notebooks only provide intermittent sales data for the years between 1812 and 1814. See Isaac Briggs' Notebook, Vol. 4, Briggs-Stabler Papers, MS 147.

^ "General Statement and Report of the business at Triadelphia from 1 mo. 1 to 5 mo. 28 inclusive 1814," written by Isaac Briggs. Sandy Spring Museum, 87.23.328 and 87.23.329.

^ C. Edward Skeen, 1816: America Rising (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2003), p. 59. This tariff raised taxes on imports of cotton goods to 25% for three years. Some historians find that the Tariff was largely ineffective until after the Panic of 1819. Isaac Briggs supported a tariff to protect the cotton and wool textile industries in 1816. U.S. House, Committee of Commerce and Manufactures, Petition of Woolen Manufactures (ASP011 Fin.476; Serial Set 476) in HeritageQuest Online, accessed 24 September 2013; See also F.W. Taussig, The Tariff History of the United States, Part I (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1892).

^ C. Edward Skeen, 1816, America Rising, 248; see also: Taussig, The Tariff History of the United States.

^ Letter, Isaac Briggs to Thomas Jefferson, 16 February 1816, The Library of Congress, The Thomas Jefferson Papers.

^ Isaac Briggs' Notebook, Vol. 6, letter (copy), Isaac Briggs to Thomas Little & Co., Wilmington, Delaware, 17 April 1815, Briggs-Stabler Papers.

^ Letter, Thomas Moore to Isaac Briggs, 26 November 1817, Sandy Spring Museum.

^ Letter, Thomas Moore to Isaac Briggs, 26 November 1817, Sandy Spring Museum.

^ Letter, Thomas Moore to Isaac Briggs, 13 July 1818, Sandy Spring Museum.

^ Fourth Census of the United States, 1820, Manufactures, Montgomery County Cotton Factory, Caleb Bentley & Co., Triadelphia, p. 235.

^ "Triadelphia Cotton Factory for Sale," Daily National Intelligencer (District of Columbia), 29 January 1825.

^ "Death Notice" for Allen Bowie Davis, Sun (Baltimore, MD), 18 April 1889.

^ MONTGOMERY COUNTY CIRCUIT COURT (Court Papers) 1777-1976, Harriet F. Lansdale, executrix of Thomas Lansdale v. Montgomery Company, June Term 1879, Trial #127, 1 July 1879 [MSA T414-78].

^ "Destructive Fire," Sun (Baltimore, MD), 10 February 1843.

^ "Fire in Montgomery County," The Sun (Baltimore, MD), 4 April 1860.

^ "The Great Freshet," The Sun (Baltimore, MD), 11 October 1847.

^ "The Storm in this Section," Montgomery County Sentinel (Rockville, MD), 7 June 1889.