|

East Baltimore |

|

East Baltimore |

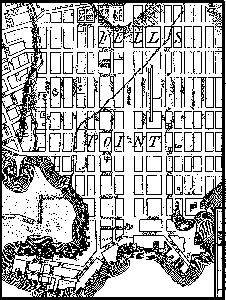

East Baltimore was a cradle of the black Baltimore community. Black Baltimoreans, slave and free, worked in the many industries which made Baltimore a vital center of commerce during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Much of this activity, particularly that which involved shipping and ship building, occurred in the eastern parts of the city, around the harbor. In the years following the Civil War, east Baltimore became a center of African American political, social, and economic activity. The area north of Fells Point deserves as much attention as that more famous neighborhood on the water's edge.

In 1870, Frederick Douglass recalled that, "forty years ago I sat on Kennard's wharf, at the foot of Philpot street and I saw men and women chained and put on ship to go to New Orleans. I then resolved that whatever power I had should be devoted to the freeing of my race." Douglass reflected on that pivotal moment in his life during a speech he gave at the largest gathering of African-Americans prior to the 1950s. The locality he refers to, while singularly important as the site where a great man made a monumental decision, was an important African American neighborhood in its own right. Douglass' national fame eclipsed the supporting cast of local leaders from the search light of popular history. African-American leaders Isaac Myers, John W. Locks, and John A. Fernandis, among others, lived, worked, and worshipped in that section of Baltimore. These names may not sound familiar. They have waited in obscurity until now.

East Baltimore fostered an active, vibrant African American community. African American leaders in business, politics, and society moved in circles which centered in East Baltimore. They may have lived on Biddle or Orchard Streets, but they often met and worked with people on South Wolfe, just north of Frederick Douglass' dock. A resident of South Wolfe in the late 19th century could have seen Frederick Douglass, Isaac Myers, and many other notable figures daily. These men pioneered new frontiers for African-Americans in business and society and deserve to be acknowledged for their work.

Such men often crossed paths on South Wolfe St., north of Fells Point. John Locks owned several properties there and lived at 214 South Wolfe. His hack service was two doors to the north. John Fernandis was a very politically active barber and Locks' brother-in-law. Whitfield Winsey, a highly respected physician, also owned property on South Wolfe St. Isaac Myers was Locks' colleague; both men were officers of the Chesapeake Marine Railway and Dry Dock Company, just a few blocks south of Locks' house. Each was active in promoting the advancement of the African American citizen in Baltimore and had common political goals. Locks also had an extensive political and business relationship with Alexander Hemsley, a funeral director and undertaker. Hemsley needed a steady supply of hearses which Locks supplied. Hemsley ran a prosperous business and provided his services to the Locks family, and the families of many USCT veterans. Everett J. Waring, a talented lawyer, extended his legal services to the Locks family. Mary Ann Locks, John Locks' second wife, filed her will with Waring during his tenure in Baltimore. Dr. Whitfield Winsey was the attending physician at the death of Theodore Locks, John Locks' son.

Even as West Baltimore opened up to blacks during the late-19th century, many continued to maintain a presence, professional and residential, in the eastern part of the city as well. While recent works continue to reveal the significance and the contribution of "Old West" Baltimore's black residents during the twentieth century, less known are feats of late-19th century blacks in East Baltimore who bridged the leadership gap between civil war generation and the twentieth century. These Baltimoreans pioneered new frontiers for African Americans in business and society and deserve to be acknowledged for their work.

![]() Return to The Road

From Frederick To Thurgood Introduction

Return to The Road

From Frederick To Thurgood Introduction

|

Tell Us What You Think About the Maryland State Archives Website!

|

© Copyright February 03, 1998 Maryland State Archives