|

Dr. H.J. Brown:Political Activism |

|

Dr. H.J. Brown:Political Activism |

In 1867 Maryland's Republicans held a convention in Baltimore for the purpose of addressing the political and civil rights of citizens. Dubbed "the Border States Convention", Republicans assembled at the Front Street Theatre during September. In recent years, the Republican/Unionist Party had been losing considerable influence in state government. However, the party seemed poised to stage a serious fight for universal manhood suffrage. It was hoped that if suffrage could be won for black men, the Republicans would create forty-thousand new loyal partymen.

Maryland's recognized black leaders converged in force on the convention. Dr. H.J. Brown was appointed to a Committee of Nine on the Permanent Organization at the convention. Focusing his message on the theme of the convention, black suffrage, Brown first denied that black suffrage would ignite a race war, as Southern Democrats had suggested. Speaking in a tone of defiance Brown declared that Southern "rebels" owed black Americans for two-hundred and fifty years of free labor. He proposed that the U.S. permanently confiscate the conquered Southern territory for redistribution to the freedman. Land ownership, Brown told the audience, was the true road to freedom and equality for blacks. Later during the summer of 1867, the Union League of East Baltimore, a Republican club, appointed Dr. Brown as one of several colored citizens on its committee of one hundred to lobby Congress for support of universal manhood suffrage.

When the state's Republicans gathered at the Front Street Theatre the following year, in March 1868, all the black Republicans from Baltimore City were refused seats on the floor of the convention, and had to take the spectator's view from the galleries of the hall. The leaders of the convention were determined to suppress the issue of universal manhood suffrage--it would have been "inexpedient to force it on the people now." Mainstream party leaders believed instead that the immediate objective of the party should be the election of U.S. Grant to the presidency. Many delegates left the convention at the Front Street Theatre in protest. The protestors gathered later that night at the Douglass Institute on Lexington St. Led by Judge Hugh Lennox Bond, they decided to hold their own Republican state convention later in the spring, with the intention of producing national convention delegates and resolutions more sympathetic to the cause of universal manhood suffrage.

The dissenters' convention was held on May 6, 1868, just two weeks before the nation's Republicans were to gather in Chicago. They gathered at the New Assembly Rooms on Hanover Street. H.J. Brown stood to address the convention. He accused the Republican press of Maryland of intimidation tactics designed to discourage black Republicans from attempting to vote. More than likely, that remark was directed at Charles C. Fulton, editor of the Baltimore Weekly American. As Brown continued, he confirmed that the attempts to keep black men out of politics were in vain: "The day is coming when the black man will vote, and he will be the balance of power. He will then stand by well-tried and true friends."

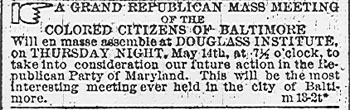

Apparently less than satisfied with the results of the "Hugh Bond

Convention," Baltimore's black Republicans called a meeting at the

Douglass Institute.  About

four hundred citizens (only twenty of whom were white) attended the meeting.

H.J. Brown stated that the purpose of the meeting was for black Republicans

to erect a platform for the entire party in the state to stand on. Another

speaker, William F. Taylor addressed the gathering and encouraged black

Republicans to "remain entirely aloof" to both wings of the party,

and to "pledge themselves to no faction," until suffrage and

full party participation was achieved for black men.

About

four hundred citizens (only twenty of whom were white) attended the meeting.

H.J. Brown stated that the purpose of the meeting was for black Republicans

to erect a platform for the entire party in the state to stand on. Another

speaker, William F. Taylor addressed the gathering and encouraged black

Republicans to "remain entirely aloof" to both wings of the party,

and to "pledge themselves to no faction," until suffrage and

full party participation was achieved for black men.

The participants adopted resolutions pledging support to either faction of the party willing to allow black men to vote in the party primaries. Those gathered at the Douglass Institute also asserted the necessity of black manhood suffrage so far as, "it gives the colored man a practical understanding of party machinery, inducing them to take more interest in state and national affairs."

White mainstream Maryland Republicans continued to restrict black participationin the election process. Until 1870, as Margaret Law Callcott has written, blacks were excluded from ward meetings, primary elections, and state conventions. Through 1868 and 1869, they found themselves regarded merely as consultants.

Though Brown remained politically active after the national ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment--he served as master of ceremonies to the citywide parade of twenty thousand participants and spectators on May 19, 1870 -- his personal life and livelihood began to reflect his improving social status. Brown took advantage of his political connections by securing for himself, as early as 1873, political patronage positions with the United States Custom House, located at 110 Smith's Wharf in southeast Baltimore. This was a prestigious position for a black Baltimorean to hold.

Brown's social status, however, did not translate into an apathetic outlook on the plight of fellow black Marylanders. In spite of his position with the custom house, Brown was a vocal champion for other blacks seeking federal employment opportunities in Baltimore during the 1880s. Brown criticized the Republican Party of Maryland at a January 1880 meeting of black Republicans held in the Douglass Institute. Addressing the gathering, he stated that fully two-thirds of Maryland's Republicans were black, yet they were treated by the empowered one-third white partymen as the "dromedaries and pack-horses" of the party. Then, he went so far as to claim that only a few blacks--including himself--had "minor" positions with the U.S. Custom House in Baltimore. There was a total absence of black Republicans from the Internal Revenue Service and sub-Treasury departments in the city, and no federally-appointed position occupied by a loyal black Republican in the rest of the state.

Aware of his own political clout within African American political circles, Brown pledged support to any member of the race involved in politics, and proposed a united effort to gather the fruits of past political toil. Also, aware of the factionalism within the black community--especially along the complexion line--Brown demanded that "woolly-headed black republicans" receive their share of patronage as well. His ultimate aim was to gain national recognition for black Republicans. He insisted that black Republicans work to send no less than eight delegates to the Republican National Convention and that four blacks go on the electoral ticket. That did not happen. When the state's Republicans met in Frederick in early May 1880, three African Americans were chosen as alternate delegates: at-large alternate, W.H. Perkins of Kent County and Third District alternates J.W. Locks and O.O. Deaver. However, the sole black man from Baltimore City chosen as a full delegate was Dr. Brown, himself. Apparently, some in the city had also considered Brown to be a likely candidate for a congressional seat in that same election, but no official campaign was ever launched.

There is evidence that Brown was keenly aware of the political tricks and propaganda campaigns that the minority white state partymen might enlist to hold power. During an 1880 speech, he warned his compatriots to ignore the charges of reverse-racism, "drawing the color line," that were used even during the first two decades of freedom as a deterrent to black political determination. Because of their sacrifices in the name of freedom, citizenship, and the Republican Party, Brown demanded a first-class party membership for all black Republicans.

H.J. Brown's frustration with the Republican party came to a head beginning in the late 1880s and continuing through to his death in 1920. Not only does he begin to support a series of isolated attempts by a number of blacks in Baltimore to win city council positions, but with such seats secured, the late 1890s saw Brown break completely with mainstream Republicans. He campaigned as a running mate to George M. Lane, a local attorney who made an unsuccessful run at the mayor's office. Brown assisted in organizing a lobby which saw Roberta B. Sheridan was hired as one of the city's first African American public school teachers. During the early twentieth century, Brown worked to organize an independent voters movement.

![]() Return

to "Civil Rights & Politics" Introduction

Return

to "Civil Rights & Politics" Introduction

![]() Return

to The Road From Frederick To Thurgood Introduction

Return

to The Road From Frederick To Thurgood Introduction

|

Tell Us What You Think About the Maryland State Archives Website!

|

© Copyright December 06, 2012 Maryland State Archives