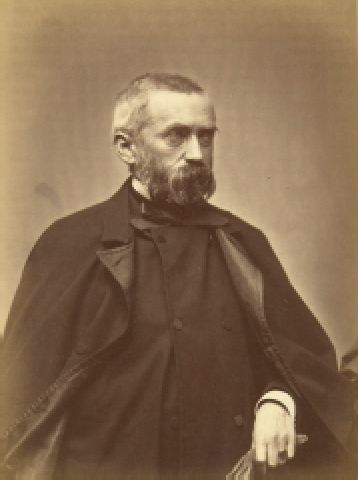

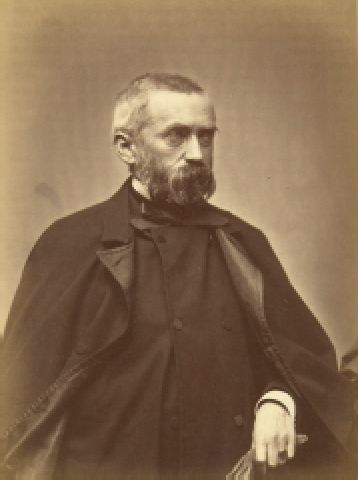

Enoch Pratt's neighbor, William

Thompson Walters, who lived in splendid quarters on West Mount Vernon Place,

came to Baltimore long after George Peabody left to take up residence in

London. The son of a Philadelphia banker, Walters was educated to be a

civil engineer. He was sent to manage a smelting operation in Lycoming

County, Pennsylvania, and produced the first iron manufactured from mineral

coal in the United States. Walters arrived in Baltimore in 1841. He opened

a general commission business and later, in 1847, became a wine merchant.

Walters presided over the first line of steamers between Baltimore and

Savannah and became heavily involved in railroads in the South. His sympathy

and strong connections with the Confederate States prompted him to take

up residence in Paris during the Civil War.

After the war, he returned to Baltimore

and capitalized on his ties to the South. He was involved in the consolidation

of the Atlantic Coast Line, comprising over 10,000 miles of track. He served

as art commissioner for the United States to the Paris expositions of 1867

and 1878 and for the Vienna exposition in 1873. Walters served as a trustee

of the Peabody Institute and chaired its Gallery of Art committee. A patron

of Antoine Louis Barye, he purchased a fine collection of the French sculptor's

works for his own gallery and acquired a collection for the Corcoran Gallery

of Art in Washington as well. He served as chairman of the acquisitions

committee and as a permanent trustee of the Corcoran, founded by George

Peabody's close friend and business associate, William Wilson Corcoran.

Walters Public Baths

Baltimore’s late nineteenth-century

Progressive reformers worked diligently to overcome the problems of quotidian

life in their crowded and dirty industrial city. A Federal government report

in 1893 noted that in some sections of Baltimore, ninety per cent of the

residents lacked sanitary facilities in their homes. The city had outgrown

its ability to serve its residents. There was no sewer system and garbage

piled in the alleyways. There were few paved roads. Waves of immigrants,

perceived by many local residents as threats to the health of the populace

by their sheer numbers, added to the demand on city services.

A public bath movement arose in

1893 when the Reverend Thomas Beadenkopf of the Congregational Church in

Canton approached Canton Company president Walter Brooks for permission

to convert one of the company’s abandoned wharves into a public beach.

Brooks granted permission and Beadenkopf secured funding for renovations

to the wharf. Within a year the minister raised funds for two additional

bathing shores. City leaders supported these projects and the idea of year-round

facilities quickly caught on with the public. Henry Walters worked aggressively

for enabling legislation. In 1899 he pledged to build three bathhouses

and open them to the public regardless of ability to pay. The Walters Public

Baths served as a nationwide model, reaching as far as San Francisco and

its Sutro Baths. By the 1920s, Baltimore's free public bathing system included

five freestanding buildings, portable bathhouses, swimming pools, and facilities

in public schools, which served citizens until 1954, when the last bathhouse

closed. |