|

| |||||||||||

|

White House History was introduced in 1983 as "a journal of history devoted to the White House." Since then, the White House has passed the 200th anniversary of its beginning in 1792 and will reach the bicentennial of its occupancy by President John Adams on November 1, 1800. These milestones make us reflect on the long and unique history of the First House. Every president but one has lived there, the lone exception being George Washington, who directed the building of the house. The White House Historical Association presents this journal not only for the benefit of professional historians, but also for those with an interest in the White House who want to know more. Robert

L. Breeden - Chairman of the Board of Directors, White House

Historical Association | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

|

The word "style" has become so ubiquitous in descriptions of the Kennedy White House that a future scholar could be led to believe that all earlier residents of the famous house lived within its walls uninspired. While there may be some truth to this conclusion in a very few cases, evidence of the undeniably stylish interiors of such presidents as Chester Arthur, Benjamin Harrison, and Theodore Roosevelt is well documented. 1 Later 20th-century presidents, including Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, and Bill Clinton also left their own decorative arts impressions on the White House, some even surpassing the Kennedys in the acquisition of period furnishings and efforts to re-create the historically accurate. 2 And while the Kennedys, and particularly Jacqueline Kennedy, are often credited with restoring history and beauty to the White House through a program of "restoration" rather than "redecoration," their efforts were not unique, as the earlier work of Grace Coolidge and Lou Hoover would attest. 3 Why then, 40 years after their fabled "thousand days" in the White House, do John and Jacqueline Kennedy remain firmly fixed in the national consciousness as the arbiters of good taste in the White House and the most prominent champions of its role as the premier historic house in the nation? Certainly the reason has much to do with the brevity of their days as president and first lady and the tragic circumstances that ended the Kennedy administration. Just as surely, the enormous popular appeal of this young couple, who personified the glamour and sophistication of 1960s high society, left much of the nation star struck: Hollywood could hardly have cast a better pair for the roles of host and hostess of America ' s New Frontier. But while these elements account for the Kennedys' permanent status as international style icons, it is the substance of their style that marks their true contribution to the history of the White House. The Kennedys' personal interest in making their home a showcase of art and culture ultimately reached beyond the walls of the White House to affect the American people's sense of their own history. Coinciding with the burgeoning industry of printed media and television, and preceding the age of tabloid journalism, the Kennedys' residence in the White House occupies a unique period in history, a period ideally suited to broadcast their ideas to the nation and seal John and Jacqueline Kennedy's place among the most stylish residents of the White House.

Kennedy's inauguration in January 1961 lit a spark of enthusiasm among the many artists and writers who were invited to attend. The inclusion of eminent American poet Robert Frost among the speakers that day was heralded as the first artistic achievement of the Kennedy administration and a sign that the arts would play a prominent role. 5 Fortunately, for those hopeful for government advocacy of the arts, at the president's side was a first lady whose cultured tastes and interest in history equaled and, by most accounts, surpassed his own. Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, at 31 one of the youngest first ladies in history, had strong interest in and knowledge of art and literature. Her education in fine art and literature complemented the president ' s deep interest in history and biography. Longtime friend William Walton described the Kennedys' mutual interest in the arts saying, "It is woven into the pattern of their lives." 6 It is no surprise, then, that advocacy of the arts became a priority during their time in Washington. But while previous first ladies chose to pursue their interests quietly, in the shadow of their husband ' s work, Jacqueline Kennedy quickly emerged on the national scene as a leader in her own right. By choosing to focus her attention on the home, she managed to stay within the traditional confines for women of the period. However, her efforts to dramatically enrich the image of the White House mark a serious attempt by a first lady to establish her own national agenda. In her prize-winning essay for Vogue's "Prix de Paris," written at the age of 21, Jacqueline Bouvier imagined herself an "Over-all Art Director of the Twentieth Century." 7 The prescience of her words is remarkable given the influence she ultimately had on fashion, interior decoration, and architectural preservation from the early 1960s until her death in 1994. A disappointing visit to the Executive Mansion when she was 11 left a deep impression, one she immediately acted upon when she knew she was to become first lady. Recalling that visit, she told journalist Hugh Sidey, "From the outside I remember the feeling of the place. But inside, all I remember is shuffling through. There wasn't even a booklet you could buy. Mount Vernon and the National Gallery and the FBI made a far greater impression." 8 She experienced this same feeling of disappointment after touring her new home with Mamie Eisenhower in December 1960. Accustomed to living in houses furnished with fine antiques and in interiors that reflected the social position of her family, Mrs. Kennedy was shocked to realize that the president of the United States was expected to live and entertain in rooms that she felt resembled a second-rate hotel. By then Jacqueline Kennedy was already planning the conversion of the family quarters into a suitable living space for her and the president and their two young children, having secured the services of society decorator Mrs. Henry Parish II. A doyenne of domestic interiors, " Sister" Parish was yet to achieve her ultimate fame as the senior partner in Parish Hadley, and mentor to a generation of decorators, when she conspired with Jacqueline Kennedy to transform the private rooms of the White House into a home suitable for a young family. Within two weeks of moving into the White House, the Kennedys had spent the entire $50,000 appropriation for improvements on the private quarters alone, which included the creation of a kitchen and private dining room for the family. Sister Parish's characteristic chintz-laden, casually elegant style defined the family rooms, which in some part were re-creations of the interiors of the Kennedys' Georgetown townhouse.

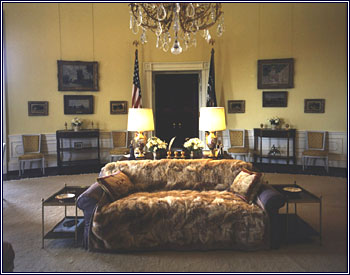

Satisfied that her family would have suitable accommodations, Jacqueline Kennedy expanded her redecorating plans to include the State Rooms of the White House as well. Even before moving in, she began educating herself about the history of the White House and its furnishings, requesting that relevant material from the Library of Congress be sent to her in Palm Beach, where she was recuperating from her son John's birth prior to the inauguration. Not satisfied merely to replace curtains and carpets, as might be expected of any new president's wife, Jacqueline Kennedy was determined to obliterate the institutional aesthetic that pervaded the White House and make it instead a home reflecting the lives of those who had lived there and the historic events that had taken place within its walls. Instead of department store reproductions, she envisioned museum-quality furniture from the period of the earliest occupancy of the White House. Dismayed by the prevalence of 1950s-era carpeting and curtains, she envisioned grandly designed window treatments and rugs based on historic documents. And where there was little to show visitors that evoked the great story of America and its people, Jacqueline Kennedy envisioned a White House that was a showcase for the finest examples of American art and culture-a residence befitting the nation ' s highest elected official, with an American stateliness and grandeur to match in power the palaces of Europe. Jacqueline Kennedy made the unprecedented move of leaking her plans to the press even before her husband was inaugurated. 10 Not intimidated by warnings that the public would not approve of the first lady making changes to the White House, Jacqueline Kennedy trusted her instincts that if done correctly, a redecoration based on "restoration" would be viewed as a legitimate initiative for the president's wife. Similar ideas of establishing historic "period" decoration in the White House had been pursued by Grace Coolidge in 1924, Lou Hoover in the 1930s, and even Mamie Eisenhower in 1960. 11 Decoration by committee had been an established method for making decorative changes within the White House since the mid-1920s. Seen as a way to circumvent public criticism of first ladies' efforts to redecorate, these advisory committees often failed to achieve their goals due to internal conflict over how to proceed with the various "restorations" of White House rooms. 12 Where earlier efforts ultimately lacked significant impact on the White House interiors, Jacqueline Kennedy ' s program had the benefit of better historical timing. Grace Coolidge ' s efforts in soliciting historic furnishings for the White House had elicited no excitement from the public during the burgeoning Colonial Revival period of the early 1920s, but in the years following World War II, when the United States viewed itself firmly as the pr emier world power, interest in Americana had become more prevalent. Furthermore, recent tax laws had made charitable giving far more appealing to those able to make significant donations. The first lady ' s enormous public appeal and social connections also played a major role in the success of her program. The Kennedys had the ability to call upon a host of wealthy and influential friends to donate to the project. And those who did get calls already knew Jacqueline Kennedy from her days as a debutante and senator's wife and were now eager to become acquainted with the new first lady who was quickly becoming the most admired woman in America. This admiration proved mutually beneficial; wealthy donors became "friends" of the Kennedys and the White House received furnishings priced far beyond any government appropriation.

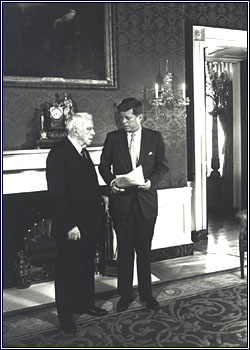

With the Fine Arts Committee securing donations, mass media secured the admiration of the public. By 1961, most Americans owned a television set and were inundated daily with images of the glamorous first family. 14 Magazines and newspapers, already focused on every move the Kennedys made, created a cause célèbre of her initiative to beautify the White House. A plethora of women's magazines and the popularity of "women's pages" in newspapers provided a constant forum for tidbits of information about Mrs. Kennedy's redecoration of the White House. The first lady's appeal for public assistance in her efforts to restore beauty and history to the White House captured the national imagination. Immediately offers of furniture began pouring into Winterthur's post office, where Henry du Pont's secretary dutifully replied to each letter describing "Grandma's rocking chair," or "a piece we've always been told came from the White House." For the first time, Americans felt welcomed into the process of decorating the White House. And while most of the furnishings acquired between 1961 and 1963 were found through antique dealers and committee members, a few important pieces came directly from public solicitation. Most important, the public's interest in the program led to a renewed appreciation for the house and its history. Improved mass transportation meant that more people than ever were traveling, and the White House became a "must-see" destination in the nation ' s capital. The publication of the guidebook-a book Jacqueline Kennedy's critics feared would commercialize the White House-meant that everyone could take something home from what was now regarded as the most historic house in the nation. The televised tour of February 1962 was the pinnacle media event of its day. The television camera so adroitly exploited by her husband during the 1960 presidential campaign in turn became Jacqueline Kennedy ' s tool in forever sealing the public's approval for her refurbishment of the White House. Henry du Pont's role as chair of the Fine Arts Committee placed him in the most public role of defining the Kennedy interiors. As far as the public was concerned, it was the antiquarian du Pont, revered as the most important collector of American decorative arts of his day, who would be responsible for ensuring the historical integrity of the White House State Rooms. Du Pont's former home turned museum, Winterthur, outside Wilmington, Delaware, contained nine stories of period rooms representing American interiors from the 17th through the 19th centuries. Jacqueline Kennedy visited Winterthur in May 1961 and looked to it as a model for the authenticity she hoped to bring to the White House. But while du Pont's connections in the world of American antiques proved useful to the project, the fact remained that the White House was not a museum. In spite of the passage of Public Law 87-286 in September 1961 declaring a permanent White House furnishings collection and the establishment of a curator's office, the primary function of the house as an official residence called for a grandiosity that transcended a museum interior. 15 Thanks to Jayne Wrightsman, Jacqueline Kennedy called upon the services of Europe's celebrated society decorator, Stéphane Boudin, to infuse an international perspective into the decidedly American house. The principal designer for the Parisian firm Jansen & Co., Boudin had worked with such high-profile clients as the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Elsie de Wolfe, and Lady Olive Baillie. Boudin was celebrated for his ability to translate a sense of historical grandeur in rooms comfortable enough for modern living. While he also guided the restoration of historic interiors such as Empress Josephine's Malmaison, a museum house, and for Charles de Gaulle's guest house, the Grand Trianon at Versailles, Boudin ' s work was not characterized by a strict adherence to one historical period but rather by a more artistic interpretation of the past. 16 Ironically, it was Boudin ' s international style that became representative of the newly restored "American" interiors in the White House.

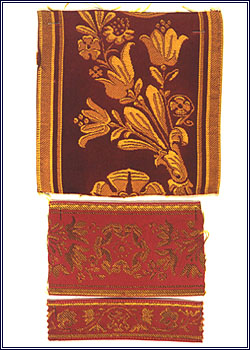

As the White House interiors evolved, with each room's period furnishings described in scholarly detail to the American public, history came to represent good taste. Prior to the Kennedy restoration, America's idea of historical interiors was largely shaped by images of Colonial Williamsburg with its staid, white plaster walls and simple brown furniture. The restoration of the White House interiors under Jacqueline Kennedy's direction inspired a national craze for preservation. Mrs. Kennedy's program has been emulated in public residences throughout the country. During the 1960s, governors' mansions in several states undertook historic restorations of their interiors, often simultaneously establishing furnishings committees and nonprofit foundations to ensure long-term preservation. 18 The fabrics produced for the White House took on an immediate authenticity based on their use in America's most famous historic house. Individual elements of the restored White House rooms, such as scenic wallpaper and the celebrated gold-embroidered cerise fabric produced for the Red Room (based on a 19th-century document) became immediately recognized icon s of 19th-century American period design. To this day, the Manhattan firm of Scalamandré, Inc., the original manufacturers of the Red Room fabric, leads their promotional material with a reference to their involvement in the creation of the Kennedy White House interiors. 19 By November 1963, much of Jacqueline Kennedy's vision had been realized, including the redecoration of her husband's office, which was being fitted with new curtains and carpeting while the Kennedys were away in Dallas. What began as public fascination with Mrs. Kennedy and her project became a reverential respect for the vision of this brave young widow. Had there been a second Kennedy administration, perhaps more criticism would have emerged, of the kind introduced by Maxine Cheshire. Over the ensuing years, with the inevitable change that comes to all public residences, critics appeared within the White House itself. There was even what has been referred to as a "de-Kennedyization" of the interiors during the Nixon administration, which political analysts might attribute to President and Mrs. Nixon ' s continued hard feelings after the loss to Kennedy in 1960 but which was also fueled by changes in curatorial scholarship in early American design. 20 Regardless of questions about its historical accuracy, no other administration can claim so many achievements in preserving the White House for future generations. The years between 1961 and 1963 are a watershed in White House history. Though marked by good intent, all earlier attempts to "restore" a historical appearance to the White House failed due to lack of infrastructure and government support to back up the efforts. The Kennedy restoration ensured that never again would White House furniture be auctioned off indiscriminately or "lost" in a warehouse. The office of the White House curator, initially one person operating out of a ground floor storeroom, now houses a small staff devoted to the preservation and interpretation of the White House Collection. The effort within the White House is backed up by valuable external support from the National Park Service. And Jacqueline Kennedy's Fine Arts Committee has evolved into the Committee for the Preservation of the White House, continuing to oversee all aspects of the decoration of the State Rooms. The Kennedy restoration, so clearly identified as Mrs. Kennedy's initiative, also marks the most significant shift in the identity of America's first lady away from the traditional White House hostess. Since then, first ladies have assumed increasingly more prominent roles and are, in fact, expected by the public to work as advocates for national issues. A 1961 article in Horizon magazine documents the achievements of John and Jacqueline Kennedy in supporting the arts in Washington and sponsoring the law to preserve the historical integrity of the White House interiors. In it, author Douglass Cater praises the Kennedys for their efforts and asks the rhetorical question, "Could a future President and First Lady use the same discretion in promoting culture as the present ones?" 21 Fortunately for the White House, the protective measures put in place by the Kennedys ensure that while less culturally motivated residents may move in, the likelihood of any diminishing of the historical integrity of the house is minimal. As for future residents who aspire to be style-setters to the nation, the brilliant precedent set by the Kennedys will undoubtedly cast a long shadow over their efforts for years to come.

Endnotes 1. For a comprehensive study of restoration and redecoration in the White House prior to 1960, see William Seale, The President ' s House: A History (Washington, D.C.: White House Historical Association, 1986). 2. The most prolific period of acquisition of 18th- and 19th-century furnishings occurred during the tenure of Clement E. Conger as White House curator. Conger guided the development of the White House Collection from 1970 to 1986. 3. Grace Coolidge, in 1924, appointed an official committee of advisers to select historical period furnishings. Her campaign, while ultimately unsuccessful, did establish the precedent for period rooms within the White House, designating the Green Room as a Federal-style parlor. In the early 1930s, Lou Hoover completed a catalog of the historical furnishings of the White House, sponsoring the first serious research into the collection. In a time before curatorial control, when most of the original furnishings were already gone from the house, her efforts were of little impact. See Seale, President ' s House, for thorough descriptions of these earlier efforts to establish historical authenticity in White House interiors. 4. See William Seale, "Theodore Roosevelt ' s White House," White House History, no. 11 (2002): 29-37. 5. For a profile of the Kennedy administration ' s early advocacy of the arts, see Douglass Cater, " The Kennedy Look in the Arts, " Horizon, April 1961, 4-17. Cater states that the idea to invite artists and writers to the inauguration originated with Kay Halle, an influential Democrat and member of the Inaugural Committee. Cater further credits newly tapped Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall with the idea to invite Frost to deliver a poem as part of the ceremony. Apparently Udall became acquainted with Frost while the latter was consultant to the Library of Congress. 6. Quoted in Marianne Means, The Woman in the White House (New York: Random House, 1963), 274. 7. See Cater, "Kennedy Look in the Arts," 9. 8. Hugh Sidey, "The First Lady Brings History and Beauty to the White House," Life, September 1, 1961, reprinted in White House History, no. 13 (2003): 6-17. 9. The most significant campaign for furnishing the private rooms of the White House was sponsored by Ronald and Nancy Reagan, who raised nearly a million dollars to redecorate the family quarters between 1980 and 1988. As cited in William Seale, The White House: The History of an American Idea, 2d ed. (Washington, D.C.: White House Historical Association, 2001). 10. See Betty Boyd Caroli, First Ladies (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 222. Caroli notes that through her social secretary, Letitia Baldrige, Jacqueline Kennedy's plans to make the White House a "showcase of American art and history" were mentioned in the New York Times on November 23, 1960. 11. See Seale, President's House, 865-70, 908-12; James M. Abbott and Elaine S. Rice, Designing Camelot: The Kennedy White House Restoration (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1997), 17. 12. Of particular note are the efforts of Harriet Barnes Pratt, who served on advisory committees for furnishing the White House from the Coolidge to the Truman administrations. Mrs. Pratt fervently pursued the goal of establishing period decoration in the White House rooms, advocating the first formal government oversight of the White House Collection of furnishings. Unfortunately her efforts, and those of others, were often thwarted by political infighting among committee members and a lack of support for funding White House acquisitions. See Seale, President ' s House, 864-70. 13. Means, Woman in the White House, 280. 14. Caroli, First Ladies, 221. 15. In March 1961 Lorraine Waxman Pearce, a graduate of the Winterthur Program in Early American Culture, was appointed the first White House curator. Pearce's expertise in the work of French émigré cabinetmaker Charles-Honoré Lannuier and in French influence on early-19th-century American interiors made her an excellent choice to oversee the installation of the new "period" rooms in the White House and to provide a scholarly voice in the restoration. 16. Boudin's decorating style and his extensive role in the Kennedy restoration are documented in the 1995 exhibition catalog, by Stéphane Boudin (Cold Spring, N.Y.: Boscobel Restoration, 1995), by James Abbott and Elaine Rice, as well as in Abbott and Rice, Designing Camelot. James Abbott has continued to document the relationship between Boudin ' s work in the White House and his redecoration of Leeds Castle, in Kent, England, for Lady Olive Baillie, for a forthcoming publication. 17. Maxine Cheshire, "They Never Introduce M. Boudin," Washington Post, September 9, 1962. 18. See Cathy Keating, with Mike Brake and Patti Rosenfeld, Our Governor's Mansions (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1997). 19. It was Stéphane Boudin who supplied the historic document for the Red Room fabric to Scalamandré. Unbeknown to the American public, Boudin also supervised the production of the famous Blue Room "eagle" fabric, which was secretly produced by Tassinari and Châtel in Paris. See Abbott and Rice, Designing Camelot, 115. 20. James Abbott, "Restoration: Twenty-Five Years of Interpretation," bachelor's thesis, Vassar College, 1986. Abbott describes Clement E. Conger's direction of the White House interiors away from what the latter considered to be European-inspired decoration and to establish more authentic American period rooms. Interestingly, some later presidents and first ladies have returned specific elements of the Kennedy era to the White House rooms, perhaps in homage to the restoration of 1961-63. Examples include Nancy Reagan's placement of a center table in the Blue Room and the return of a tentlike valance to the same room during the Clinton administration. 21. Cater, "Kennedy Look in the Arts," 17. |