By Corinne F. Hammett

He's worked with the U.S. Army's Patriot Air System, building simulators to test how humans would react to the bold, new aircraft; helped design high performance computer systems and Army Research Lab prototypes--34 years of skilled, sometimes top-secret projects. Years of working in a lab, traveling cross country, putting ideas on paper and into simulators that might one day become valuable to soldiers and scientists.

Retirement in January 2000 brought him to a crossroads; "stay home and watch the grass grow," or put his electronic engineering skills and inventive mind to work by dreaming up unique technological devices to make life better for disabled persons.

For Gordon Herald, of Bel Air, MD., it was an easy choice. "In the Army we sometimes had to wait 20 years before a problem we worked on actually culminated in a usable piece of equipment. Now, not only do I have the satisfaction of being challenged to develop something unique, but I can actually see it being used, helping someone to get some enjoyment out of life."

Herald, 66, doesn't have time to "watch the grass grow"; he's too busy designing and building one-of-a-kind devices for persons who need "just that one piece of equipment" to achieve a specific, important goal.

As one of the Volunteers for Medical Engineering, (VME) in Baltimore, Herald has put his talents to work on numerous devices, such as the gizmo to enable someone with limited use of hands and arms to turn on a TV set, change channels and adjust volume. He also found a way so that someone with cerebral palsy whose speech lacks clarity, can ask for a glass of water, please, or convey other necessary messages. He's always looking for devices he can alter to another use, for example the channel changer consists of a box built to contain the electronics; then Herald bought an inexpensive remote control from a chain store and modified it to go with the new switches.

VME has a primary partnership with the Maryland State Department of Education's Division of Rehabilitation Services and the Maryland Rehabilitation Center, in Baltimore.

Jan Hoffberger, executive director of VME, explains that VME designs assistive devices for persons who need a piece of equipment that is not commercially available. "Actually, if some of these devices were available on the market the cost would be prohibitive." The process works this way; "VME receives a request and sends out a team to visit with a client, and the caretaker or teacher if the client is a student. We want people to come to us and say, 'I'm having trouble doing this, what can you do?' Rather than someone coming to us and saying they need a specific item; that can be difficult to satisfy. Perhaps they think they need a whizzet when they really a whatsit. Our engineers are trained to look at a situation and come up with a solution."

Once the project gets the go-ahead from the review committee--"we're very careful with the selection process," says Hoffberger--a VME team assesses the environment and the functional abilities of the individual; the project is matched with a volunteer who develops an engineered solution. VME absorbs all costs of materials. The labor and design work is donated by the volunteers, who sometimes donate materials too, so there is no cost to the individual who receives the device.

Herald began using his talents for designing unique devices while working with the Army, donating his free time to helping students at a school for the severely disabled in Harford County, MD. That led him to VME, where he also began donating his skills, prior to his retirement.

A quiet, mild-mannered man, Herald confesses that when he solves a problem he jumps up and down shouting eureka! "Only in my head." Ideas come to him, he says, when reading trade journals, "the best way to keep up with the latest technology," while on a Web page seeking information, when he's at home in his lab tinkering with electronic devices or sometimes, just when he's relaxing. While Herald keeps current with technology, much of what he's developed so far has been the result of his ideas and technology that is 20 years old, merged with 1990s techniques. "A lot of work for human beings does not need high speed or high precision, you can only hit a switch so fast, for example. The disabled need special devices and that takes the edge off modern technology, and places emphasis on the need for human interface, done right," he says.

Some of his devices have been fairly simple such as the "Beeper Ball" built for a visually impaired child. He hollowed out a "nurf" ball and inserted a beeper and battery so the child could roll the ball back and forth and use sound to find the toy. An infrared switch on a small box-like gadget allowed a student to pass their hand near a switch and turn on the TV or another appliance. He built a second box to keep the beam on target and to get rid of cables that posed a hazard for the student.

Herald's Activity Stimulator was designed to reward a student and keep them focused on a specific task. When the student stays focused on the desired task, the Stimulator plays a clapping sound, or perhaps music, to encourage the student to continue. "I spent about 30 hours on this, and maybe $50 in parts; you can't buy this sort of thing because there's just not a big market for it, and on a small scale, it would be too expensive to produce."

The Dream Talker is a Herald variation on something that is commercially available, but expensive and too large, at 10 to 12 inches for a disabled person to carry around conveniently. "People also objected to it because the device drew attention and proclaimed that the person was disabled," Herald says. His version, at six by four inches, can go into a pocket or handbag. Buttons allow the user to select from one to 16 different pre-recorded messages that can then "voice" a need. The Talker was designed for persons who may be working outside of their home environment and need to "know what time it is," "make a phone call" or "buy lunch" but cannot be easily understood because of speech problems. "People become very attached to these, they are a security device for them."

While all of Herald's devices demand ingenuity and skill, the request that took the most time, over a year, and has been the most challenging, came from a visually impaired college student in a wheel chair who needed to be able to get around on campus. "One problem was that the person needed both hands to guide the wheelchair."

What he came up with is a sensor system, mounted on the chair, containing voice commands that tell the individual to turn the chair to the right or left, depending on how far the chair has drifted off course. "The sensors look down on a piece of reflective tape on the floor, or sidewalk, and while the person is on course, it emits a tiny 'ding' sound, but if the chair starts to drift, the voice command comes on. This would be a good way to train someone who is losing their vision, or a newly blinded person who needs to navigate around in a fairly controlled area. But the tape can go anywhere. Outside, we could adapt the sensor to use the Global Positioning System, or use the type of reflector tape that goes onto highways to divide the road," says Herald. One problem outside would be that he would need to find a way to shield the sensor from bright lights or sunlight.

D.

D.

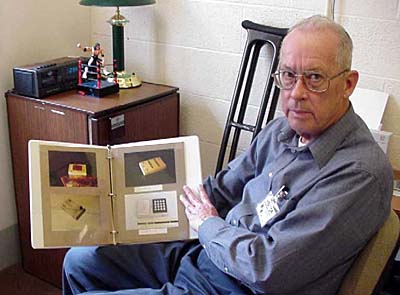

VME volunteer Gordon Herald, of Bel Air, MD, a retired electrical engineer, shows the sensor-sensitive wheelchair he designed that uses voice commands to direct a visually impaired user to stay on a specific path. The sensor device is located under the chair.

Because the device took so long, the original client no longer needed it, but now the chair is used in VME demonstrations and can be adapted for numerous other needs. "The request was so complicated," says Hoffberger, "we had set it aside for a time until Gordon came along and took the project on, but we can utilize the technology for future requests."

And that's another plus for VME; the group has a great deal of flexibility. VME's successes are numerous and each is unique. That's what keeps people like Herald working to dream up a whatzit so that one more disabled person can enjoy a successful solution to a problem.

D.

D.

Gordon Herald, of Bel Air, MD, a retired electrical engineer, keeps photos of devices he's designed for the disabled in a portfolio. Shown, on left, is the Proximity Switch Channel Changer and the Activity Stimulator. On the right is the Dream Talker for use by persons whose speech lacks clarity.