II. Overview

In 1633 Cecil Calvert, Second Lord Baltimore, had a vision of what his new colony on the Chesapeake should be. Instructions to his brother and the other leaders of the expedition carefully outlined what he expected of this grant of land to the northward of Virginia, called Maryland after England's Queen:

they were to first make a choice of a fit place for a fort with in which or near to it a convenient house, and a church or chapel might be built;

that they should cause all the planters to build their houses in as decent and uniform a manner as their abilities and the place will afford, and near adjoining one another,

and for that purpose, to cause streets to be marked out where they intend to place the town and to oblige every man to build one by another according to that rule.

Maryland was to be a new city in the wilderness, not unlike the best London had to offer. Instead the colonists bought an existing town on the banks of a river now called St. Mary's from the Yoacomacoes indians. They then proceeded to make the most of what they had purchased, including planting corn and making gardens “which they sowed with English seeds of all sorts,” undoubtedly contributing the first significant intrusions into the botany of the upper Bay. At first the colonists did try to finish their houses in accord with Calvert's instructions, keeping them within the bounds of their town which they also called St. Maries. They even had corn to spare from what they had purchased from the indians, some 1000 bushels of which they dispatched for sale at Boston, where they bought salt-fish and other commodities they needed from a community that thought them so rowdy and disrespectful that they were told not to return. 1

It would not be long however, before the lure of profits from tobacco and the ease of transportation on the Bay and its tributaries would lead them astray from the urban vision of Cecil Calvert. Within less than a generation most people would be found in the agrarian world of dispersed settlement common not only to the 9,999 square miles of Maryland but to the whole of the Chesapeake Bay Ecosystem well into the twentieth century. With dispersed settlement came a growing distrust of the urban world that manifested itself as one of the principle myths of American culture: cities are evil and to be avoided if at all possible as places fit for habitation by only the newly arrived or morally depraved.2 By the 1770s there were few Americans who would not agree with Oliver Goldsmith's swain who flees the isolation of the countryside to the city only

to see profusion that he must not share;

to see ten thousand baneful arts combin'd to pamper

luxury, and thin mankind ... 3

Perhaps more than any other political figure, Thomas Jefferson symbolizes the American attachment to the agrarian myth, and the fundamental distrust of the the city upon which it is based. In 1796, defeated in a bid for the Presidency, Vice-President elect Jefferson wrote a letter to the winner, John Adams, that Jefferson's good friend Madison, thought too revealing to deliver. In it Jefferson decried the pernicious influence of the urban politician so cleverly represented by Alexander Hamilton, and indicated a preference still shared by most Americans to avoid the problems caused by the City by hiding in the bosom of the countryside.

My inclinations place me out of his [Hamilton's] reach. I leave to others the sublime delights of riding the storm better pleased with sound sleep & warm birth below, with the society of neighbors, friends & fellow laborers of the earth, than spies and sycophants.4

Of course, neither Jefferson, nor we can really avoid the consequences of the urban world. His solution, in part, was to treat the political support gained from cities like Baltimore as necessary evils, and to prosecute (some said persecute) his former urban ally, Aaron Burr, for treason. Our options are not that simple or straightforward.

By 1776, when Baltimore, a town of about 6,000 people (850 slaves) in a colony of 250,000 (80,000 slaves), attempted to gain a modicum of representation in the General Assembly, the fear of its influence was so great, and the hope that it would not continue to grow so strong, that two representatives were begrudgingly granted with the proviso that if the population would decline, even that modest presence in the politics of Maryland would cease to be. 5 Yet it could be argued that the urban presence on the Bay is the only hope for the future of the Chesapeake Bay Ecosystem, that a return to the city would not only help to promote and preserve a balance within the ecosystem but that it would also forestall further deterioration and decline. Indeed, it might be posited that a return to Cecil Calvert's vision of what life should be like on the banks of the Chesapeake not only has the potential of saving the Bay, but also within the history of the urban presence on the Bay can be found clues to what might have been, what might be, and, perhaps more importantly, documentation of what has occurred already to benefit the whole of the Chesapeake Bay Ecosystem.

Attempting such a new view of the past will not be easy, but eminently worthwhile. As one author has eloquently put it,

The human population explosion with its accompanying technological explosion is disrupting the orderly development of the world's biosphere in a variety of ways. At the time of writing (New Year's 1990), the greenhouse effect appears to be the paramount disruption. Predictions vary as to the magnitude of the climatic change we should expect from this cause; some climatologists forsee an increase in annual mean temperatures throughout the world of as much as five degrees Celsius in fifty years. Such a change, if it comes will be unlike anything this continent has undergone since the disappearance of Wisconsin ice. ... Although anthropocentrism is usually unscientific, it does seem safe to say that “now”: is a special time, a transition period; and that we (Homo sapiens) are a special species, the unwitting cause of the transition. ... Perhaps, fifty million years hence, members of some new species of animal, interested in paleoecology, will examine the geological record. ... Will it be no more than a minor episode early in the Quaternary Glacial Age, during which some species (including Homo sapiens), perhaps went extinct and others shifted their ranges?6

As students of the past we need to look at the evidence anew and differently to see if perchance there might be material from which new lessons can be drawn and new courses for Homo sapiens charted. In some measure it is important to be irreverent with entrenched myths and well-established historical dogma, no matter how relevant and substantive they may prove be, in much the same manner as an artist like Robert Arneson expresses his view of George Washington and Mona Lisa in the baths of Coloma. 7

In that way we may re-connect the mystic chords of memory and reassert the most human of characteristics of Homo sapiens, creative adaptability to meeting the crisis caused by the sheer numbers of people inhabiting the earth.

Despite the intense distrust of, and resistance to, the urban presence on the Bay, three cities flourished for at least a time in the Chesapeake Bay Ecosystem: Baltimore (from the 1770s), Washington, and Richmond (from the 1790s). In terms of size and consequence, Baltimore was the first and the largest until recently statistically re-defined as the lesser half of a combined Washington-Baltimore metropolitan region.

The intent here is not to explore the virtues of urban sprawl. To the contrary, the objective is to investigate what is to be learned from one geographcially compact city into which, by 1920 half the population of Maryland was concentrated, to examine what an urban critic of the 1870s called “Past Follies and Present Needs,” as well as the triumphs and near triumphs of urban problem solving that intentionally or unintentionally positively affected the ecosystem of the Chesapeake Bay. 8

What then are the lessons to be learned from the largest

urban presence on the Bay? How have the resources of the city been

used to the advantage of the population as a whole and towards the promotion

of equilibrium or balance within the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem? The

answers fall into at least three broad categories: health care, land use

(including its impact on the quality of life in general), and institutional

reform (educational, governmental, and social).

possible illustrations:

17-526 New Yorker cover with children carrying machine

guns

17-441 Herman Friis topographical map of the U.S. based

upon Lobeck, 1922

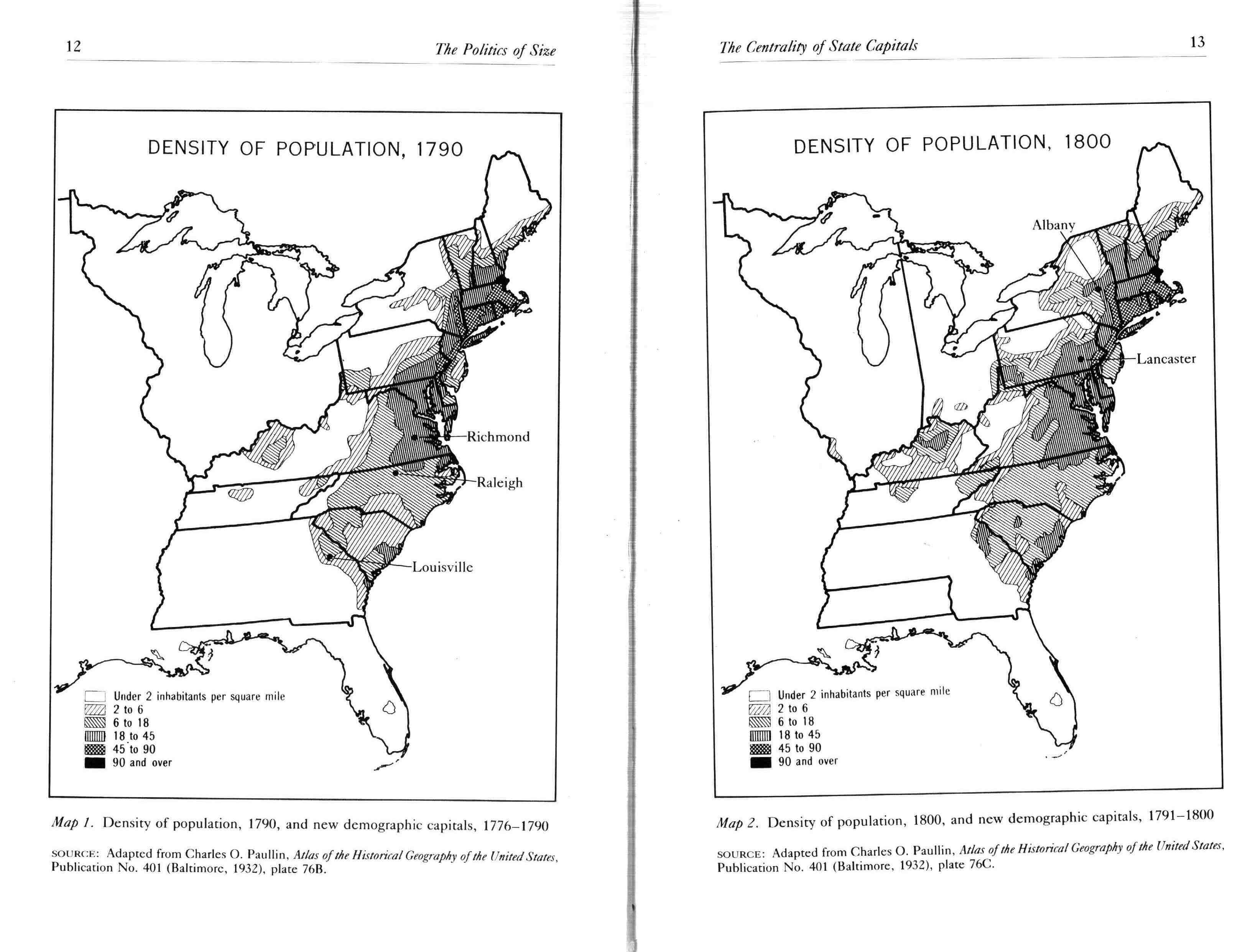

17-533 Zagarri, population density, 1790, 1800

26-395 Gunpowder watershed

26-57 Past Follies and Present Needs

17-534 George and Mona in the Baths of Coloma, 1976,

Robert Arenson