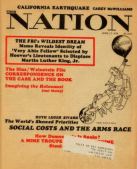

From

The Nation,

June 17, 1978

The

letters which follow, selected from among the mass of mail

we received regarding Weinstein-on-Hiss, constitute something

of an informal interim report on the case, the book and the

lawsuit against Weinstein, his publisher and possibly The

New Republic.

WARREN

HINCKLE WARREN

HINCKLE

Sam

Krieger, a Communist Party organizer for three decades, lives

today in a quiet house on a quiet street in Rohnert Park,

Calif., where Allen Weinstein came to visit him in 1974. Five

weeks later, Krieger received a strange letter that as he

now looks back on it began the noise in his life.

The

letter was from Isaac Don Levine, the lay pope of American

professional anti-communism, and its message was bewildering.

Levine wrote that Krieger's adopted little daughter, Natasha,

had arrived in America from the Soviet Union and was anxious

to be reunited with him. It was obvious that Levine thought

Sam Krieger was Clarence Miller, a leader of the 1929 Gastonia

textile strike who, with six comrades, fled to Russia (against

the wishes of the American party leadership) to avoid serving

a seventeen-to-twenty-year term for a second-degree murder

conviction arising out of strike violence in Gastonia. The

red-haired Miller was installed in a comfortable Moscow apartment

and taught political classes. He became known as the Red Professor.

He also came to know the mother of a little girl named Natasha.

Sam

Krieger wrote Isaac Don Levine that he was barking up the

wrong Clarence Miller. That was in 1974. He never heard another

word.

In

"Perjury,"Krieger, who back in the 1920s recruited

Chambers into the party, is identified as the fiery textile

strike leader who fled to the Soviet Union under the name

Clarence Miller. This serves Weinstein's melodrama by making

Chambers's recruiter a more sinister and important figure

in the party than the lowly Sam Krieger who was at that time

the circulation manager of the Yonkers (N.Y.) Statesman.

Who,

then, were Weinstein's sources on Krieger/Miller? When I called

him, he said one was a woman who heads a refugee program in

New York. Weinstein did not give me her name. She had given

Krieger's address to a mysterious Russian woman: She told

me the young woman found him and they had a sad reunion, Weinstein

said. He sounded genuinely moved. I told him that Krieger

said there had been no such visit. He shrugged over the phone.

The

other source, he said, was an anti-Communist journalist. Was

he Isaac Don Levine, I asked. Why yes, it was, he said. I

told the professor that I had talked to his source just that

morning and that Levine had said it was Weinstein who had

told him Krieger was Miller, not vice versa.

There

was a silence on the phone. That's weird, Weinstein said.

Well I have what he said in my notes. It's all here. You're

welcome to come look at them.

I

wrote an article in the San Francisco Chronicle reporting

Isaac Don Levine's recantation and the statements of two men,

Alden Whitman and Sender Garlin, who had known both Krieger

and Clarence Miller back then and said that there wasn't a

ghost of a chance that the two were the same. Bridgeport police

records supported Krieger's assertion that he was arrested

for party work in Bridgeport in 1934 when Clarence Miller

was in Russia.

If

Weinstein is right in his repeated identification of Krieger

as Miller, then Sam Krieger is a fugitive from justice and

a murderer.

On

May 24, Sam Krieger filed suit against Allen Weinstein in

U.S. District Court in San Francisco, seeking general, punitive

and special damages. In addition to demanding $1 million from

Alfred A. Knopf, Weinstein's publisher, the suit asked the

court to enjoin Knopf from identifying Krieger as Miller in

any future printing of "Perjury" and demands

that errata slips be sent by the publisher to bookstores throughout

the country to be inserted in copies already bound.

Krieger

asks damages of $2 million for Weinstein's statements in The

New Republic that he has Krieger on tape not denying that

he was Clarence Miller. Krieger said he told Weinstein exactly

the opposite, on tape. In addition, Krieger says that Weinstein

gratuitously misquoted his opinions about Hiss and Chambers

in The New Republic.

Krieger's

lawyers are Doris Walker of Oakland and John Clancy of San

Francisco, who has represented the Esalen Foundation and Hunter

S. Thompson. Clancy said that The New Republic had

been given sixty days to retract Weinstein's statements about

Krieger. If they refuse, the magazine will be named as a defendant,

Clancy said.

These

false statements, says the suit, are libelous on their face

and clearly expose the plaintiff to hatred, contempt, ridicule,

shame, fear and loathing, in that a convicted murderer

who has fled to avoid serving his sentence is not viewed as

your ordinary good neighbor.

ALDEN

WHITMAN

In

one of his defenses of "Perjury," Allen Weinstein

rounded on me as a recanter on the apparent ground that I

had told Victor Navasky I could not remember talking with

Priscilla Hiss's former sister-in-law in 1974 about whether

Mrs. Hiss had denounced her husband at a 1968 dinner party.

Weinstein thereupon quoted in part from a letter he says I

sent him in late 1974.

When

I retired from The New York Times two years ago and

moved out of New York, my files on the Chambers/Hiss case

were irretrievably dispersed. Noting this fact, I wrote Weinstein

on May 12 asking for Xerox copies of all my private letters

and memorandums in his possession. I offered to pay the costs

of copying. In view of Weinstein's repeated professions of

scholarly openness, such a request should have been honored.

I was not totally astonished, however, that he did not respond

to my letter, inasmuch as he had quoted from my private letters

and memorandums as a source for a number of allegations in

"Perjury" without my permission, consent

or knowledge.

In

footnotes in the book, he says the quotations and citations

he used are by courtesy of Alden Whitman. Nothing could be

further from the truth. The implication that I cooperated

or collaborated with Weinstein in the research or preparation

of "Perjury" is false. I did not see the

book in any form until I received a bound copy shortly before

its official publication date.

I

leave it to your readers to characterize Weinstein's behavior

and to judge to what degree it accords with standards of scholarship

that prevail generally in the history profession.

Because

Weinstein has used my private letters and memorandums without

permission and has thus miscast me as a willing participant

in his book, I have taken advice and put Alfred A. Knopf,

Inc., the publishers of "Perjury," on notice.

I have asked Knopf to give me an undertaking to excise from

future printings or editions of the book, including any paperback

editions, all citations bearing my name. I naturally pointed

out to Knopf its failure to exercise prudence in finding out

whether Weinstein had the permission of the owner of the contents

of private letters and memorandums to make use of them. Under

common law copyright, as your readers may know, the contents

of the correspondence belong to the writer.

I

would not burden your readers with this recital of my dealings

with Weinstein save for the fact that he has made a public

issue of his scholarship and his veracity. It occurred to

me that your readers should not believe that everyone shares

Weinstein's astigmatic self-view.

CUSHING

STROUT

The

Nation, as Allen Weinstein points out in "Perjury,"

has been foremost in keeping alive the hope that Alger

Hiss could be proved innocent. This political investment,

however, does not justify Victor Navasky's misrepresentation

of the historian's case. A crucial example is the editor's

account of Josephine Herbst's testimony about the Ware group.

He charges Weinstein with omission-distortion because (1)

she never used the word stolen; (2) she believed

the documents possessed by the Ware group were trivial and

intended for The Daily Worker, not Moscow; (3) she

knew John Herrmann's apartment was not used for developing

photographs while she was there.

But

Herbst did say, as Weinstein quotes her testimony, that she

had seen in the apartment certain documents that had been

taken from government offices by members of the cell and brought

to the apartment for transmission to New York. (p. 138.) She

was not claiming that the group was authorized to transmit

these documents; the absence of the word stolen, therefore,

is a mere quibble by the editor. Weinstein's fairness is revealed

by his noting that Chambers recalled no such espionage work

being done in 1934 by members of the Ware group, whose major

functions, he believed, were to recruit more Communists within

the government and to influence government policies. (p. 140.)

Weinstein

himself, moreover, makes the editor's points that she thought

the material was "innocuous" and believed that "'no

direct contact existed between our group and Soviet authorities.'"

(p. 138.) As Weinstein points out, however, she did not know

of Chambers's work for the Red Army's Fourth Branch. The historian

also notes that, while no pictures may have been developed

while she was in Herrmann's apartment, she lived there only

for three months in 1934 and hence could not speak about Chambers's

possible use of the quarters for espionage work - his and

not the Ware group's - at other times. (p. 140.)

The

editor's distortion by omission is capped, by his ignoring

the critical fact: Herbst told Hiss's lawyers that Chambers

and John Herrmann regarded Hiss as an important prospect to

solicit for the purpose of getting papers. (p. 141.)

The

evidence is clear that Chambers, Herrmann and Ware, as Weinstein

concludes, all told Josephine Herbst in mid-1934 that they

were already in touch with Alger Hiss, trying to recruit him

for espionage more than six months before Hiss claimed to

have met Chambers under more innocuous circumstances. (p.

141.) If the editor can challenge this crucial conclusion,

let him do so, rather than throw dust in the reader's eyes

by misrepresenting Weinstein's account and slandering his

character as a historian.

Note

from Victor Navasky:

In

his zeal to defend Allen Weinstein's brief, Professor Strout

seems to be guilty of the sort of carelessness which has made

"Perjury" such a dubious guide to the complications

of the Hiss case. First, he refers to Josephine Herbst's testimony

about the Ware group, even as Weinstein referred to her depositions.

In fact, all of the evidence from Miss Herbst is in the form

of FBI interviews, interviews with Hiss's lawyers or private

correspondence.

In

fact Herbst said several times that she didn't believe pictures

could have been developed in the tiny Ware apartment because

it lacked a closet and the bathroom was totally impractical

for developing purposes.

Finally,

Professor Strout seems oblivious to the bottom fact about

Weinstein's treatment of Herbst: that by citing

her statements out of historical context, he tries to use

her second- and third-hand impressions (it is difficult to

say which, given Weinstein's inadequate footnoting system)

of the so-called Ware group in 1934 as evidence of espionage

in 1937 or 1938. Especially since Herbst had no direct knowledge

of Hiss one way or the other, this seems a clear abuse of

the record.

WILLIAM

A. REUBEN

In

newspaper, magazine, radio and television interviews over

the past several months, Allen Weinstein has repeatedly said

that what clinches his case against Alger Hiss (the strongest

incriminating evidence) are memos he found in Hiss's own lawyers'

files. According to Weinstein, this evidence establishes that

early in December 1948 Hiss knew of the whereabouts of the

Woodstock typewriter he had owned in the 1930s, that he lied

about this knowledge to the FBI, the grand jury and even to

his own lawyers, and that thereafter, for five months, with

his brother Donald and Mike Catlett, the son of a former maid,

he engaged in a conspiracy to prevent anyone - government

investigators and even his own lawyers - from finding the

Woodstock typewriter.

Having

spent a quarter of a century studying the Hiss case, and in

particular having interviewed all the available witnesses

with knowledge of the typewriter, something that Professor

Weinstein, for all his vaunted research and scholarship neglected

to do, I can confidently declare these allegations by Weinstein

to be patent nonsense, complete distortions of the record.

For the purpose of economy, let me restrict myself to Weinstein's

ludicrous charge that Donald Hiss and Mike Catlett attempted

to suppress knowledge about the whereabouts of the typewriter

(a typewriter which in any case the government later claimed

was useless for its prosecution of Alger Hiss).

My

research establishes that from the time the Hiss Woodstock

was brought to the Catlett house, sometime between December

1937 and April 1938, until it or what is claimed to be

the same machine was recovered at the home of Ira Lockey,

Sr. in April 1949, the typewriter was used or possessed by

twenty-four persons, none of whom, except for Pat and Mike

Catlett, was known to Alger Hiss or to any member of his family.

In that eleven-year period, the machine was kept in no less

than twelve, and possibly as many as eighteen, different locations.

The

reader of "Perjury" is told little about

these complications and therefore is unable to appreciate

the overwhelming difficulties facing Donald Hiss and Mike

Catlett as they tried to follow this trail after eleven years.

Contrary to Weinstein's assertion, Donald Hiss never knew

that Ira Lockey possessed the typewriter in 1949. Rather than

covering up such knowledge, Donald Hiss persistently returned

to Lockey's house, no less than six times, in his quest for

the typewriter, and each time Lockey denied possession. Donald

Hiss finally and justifiably wrote this lead off as a dead

end when, directed by Lockey, a hunt through a junkyard produced

only an old Royal typewriter. Contrary to what Weinstein says,

Donald Hiss kept Alger Hiss's lawyer, Edward McLean, fully

informed about all these searches.

Fred

J. Cook (The

Nation, May 12, 1962) makes the intriguing

point that the sudden and mysterious appearance of the typewriter

in April 1949 may have been connected with an FBI visit to

Ira Lockey, Sr. in February 1949 after Donald Hiss's continuously

frustrated efforts. In any case, there is no conceivable basis

for Weinstein's charge that Donald Hiss and Mike Catlett withheld

knowledge from Alger's lawyers that the typewriter had been

traced to Ira Lockey.

Allen

Weinstein's account, which ignores almost all of this history,

is indeed the strongest incriminating evidence but it is further

evidence against the credibility.

JEFF

KISSELOFF

I

am employed as a researcher by the National Emergency Civil

Liberties Foundation. I have been spending considerable time

on Alger Hiss's pending petition for coram nobis, so

I am obviously not a disinterested bystander in the dispute

over Allen Weinstein's "Perjury." Since the

NECLF office houses the complete Hiss defense files as well

as thousands of pages of FBI documents on the Hiss case, I

have been able to compare these records with Allen Weinstein's

alleged documentation for his charges against Alger Hiss.

I have discovered, literally, more than 100 serious errors

of fact in "Perjury," some of which were

discussed in Victor Navasky's review. But Navasky's demonstrations

of Weinstein's unfounded allegations and sweeping distortions

could be multiplied manifold from the available evidence.

Take,

as an example, the question of whether Alger Hiss knew about

the location of the Woodstock typewriter in December 1948

and lied about this knowledge to the grand jury and to his

lawyers. Weinstein's sole evidence for this charge is an ambiguous

letter written December 28, 1948 by John Davis to Edward McLean.

Navasky has demonstrated that on its face the letter does

not support Weinstein's charges against Hiss, and that, far

from being certain about the whereabouts of the typewriter,

the Hiss investigators were searching in many different locations.

But

Navasky doesn't cite the strongest evidence in this regard,

a defense memorandum dated the same day as the Davis letter,

December 28, 1948, which clearly demonstrates that Hiss had

no clear recollection of what happened to the old Woodstock,

and that his suggestion to Davis (that it may have been given

to the Catletts) was only one of several possibilities that

had occurred to him. Under the caption, "What Happened

to the Typewriter," five investigative leads which the

defense intended to pursue are listed:

(i) Check

all typewriter dealers and repairmen in Washington, Baltimore,

Westminster and Lynbrook.

(Ii)

Check Hiss maids and their relatives ... Catletts.

(iii)

Relatives and friends of the Hisses to whom it may have

been given.

(iv)

Charities, such as the Salvation Army and self-help organizations.

(v)

Hiss remembers that he reported a theft to the Washington

police in 1939 or 1940. . . . This should be checked.

And,

as Navasky pointed out, the January 21, 1949 memo, entitled

"Oral Report from Mr. Schmahl Today," demonstrated

that the defense had indeed spent the previous month checking

out all these possible locations. But of course Weinstein

did not attempt to present all the evidence fairly in order

to

give the reader a chance to reach an honest judgment. Rather,

as the late Matthew Josephson, winner of the Parkman Prize

for history, wrote about "Perjury:" Weinstein

has no sense of values as a biographer or historian to lead

him through all this chaotic mass of stuff, but adopts the

standards of HUAC, the FBI, Nixon even. . . . He must destroy

the myth of Alger Hiss as America's Dreyfus case and save

the myth of Chambers as the suffering hero who rescued America's

intellectuals from Soviet communism.

SENDER

GARLIN

Allen

Weinstein introduces me several times in "Perjury"

almost always in a manner which seriously distorts the truth.

It would take too much space to provide you with even a reasonably

complete list of his mistakes, but let me offer the following

as representative of Weinstein's erroneous assertions about

me or events of which I had first-hand knowledge:

On

p. 91 Weinstein writes: In Meyer Schapiro's room at Columbia

Chambers met a young man

named Sender Garlin who was then working for Russian-American

relief.

Fact:

I was at no time associated with this relief organization.

On

p. 103 Weinstein writes that after the death of Chambers's

brother, Chambers resumed contact with Communist friends late

in 1926. He adds that Chambers also remembered that "friends

in the C.P. like Harry Freeman and Sender Garlin who were

then working on The Daily Worker, to get me out of

my mood... Urged me to go with them on that paper."

Fact:

Freeman and I (who lived in New York) could not have been

working for The Daily Worker in 1926 because the paper

did not move to New York from Chicago until the spring of

1927. I joined the staff several months later.

In

his effort to create a conspiratorial atmosphere in which

Chambers and Hiss were allegedly operating, Weinstein cites

a defense memorandum by a Hiss lawyer. Here (p. 382) I am

quoted as saying that Chambers had disappeared in 1933 and

had gone underground. Victor Navasky, in his rebuttal to Weinstein

( The Nation, May 6), quoted me accurately: Maybe the

lawyer used these words, but I did not. Words like "underground"

are not part of my vocabulary.

Weinstein

claims that among those recognizing Chambers immediately after

a decade were Sender Garlin, Josephine Herbst, Julian Wadleigh,

William Edward Crane and Maxim Lieber. His footnote, No. 59,

p. 596, cites HUAC 1, pp. 1004-5 (1948). This citation

is a phony, for I am nowhere listed in these pages of HUAC

nor are any of the other five persons mentioned, except for

Nelson Frank. Questioned by Rep. Richard M. Nixon, Frank,

a Red expert on the New York World-Telegram, said he

recognized Chambers after a lapse of twelve years. Frank testified

that he had been a part-time reporter on The Daily Worker

in 1928 when he allegedly first met Chambers. Since I

was city editor of The Daily Worker at the time, I

can state categorically that he testified falsely on this

point.

My

name appears seven times in Weinstein's index and four times

in his reference notes. However, at no time did he make any

attempt to communicate with me to check any assertions

involving me.

AB.

MAGIL

Belatedly

I have borrowed Allen Weinstein's "Perjury" and

find myself included in it as a witness. I'm not certain whether

for the prosecution or defense in the case of Weinstein vs.

Hiss. The consistent misspelling of my name and the description

of me as former editor of The Daily Worker are inconsequential

errors, whatever they may imply about the author's scholarship.

There are, however, distortions about statements I made and

about my past activity that require correction.

The

book (pp. 381-2): "Schmahl [an investigator for Hiss's

legal defense] informed McLean [Hiss's lawyer] in late January

that 'through a very confidential contact' he had learned

that A.B. Magill, former editor of The Daily Worker, 'knew

the identity of a man with whom Chambers is said to have had

an extensive affair in his younger days.' Schmahl interviewed

Magill, who described Chambers's affair with Ida Dales and

strongly implied that she and other women had been lesbians

when Chambers took up with them. Magill also said 'that Chambers

had an affair with a good-looking young boy, nicknamed "Bub"

. . . when Chambers was employed on the staff of The Daily

Worker.' Magill reiterated a theme that characterized

the C.P. line on Chambers by this time and the unofficial

comments of those Communists who volunteered information:

'Chambers was in the habit of showing Magill his manuscripts

for perusal before publication.' According to Mr. Magill,

'some of those manuscripts would turn your stomach.' They

were, said Mr. Magill, 'dripping with perversities, violence

and weird plots.'"

The

facts: I did not describe Chambers's "affair"

with Ida Dales, nor did I imply that she was a lesbian. I

referred to Ida Dales as Chambers's first wife. I did

not say that Chambers had an affair with Bub. I told the person

who interviewed me that Chambers was suspected of homosexuality,

and it was in that context that I mentioned "Bub."

I never said that Chambers was in the habit of showing me

his manuscripts before publication. He was not. I told the

interviewer that on one occasion in the summer or early fall

of 1931, while I was a house guest of Chambers at his home

on Long Island, he showed me two or three short stories and

a poem. I was impressed with the quality of the stories, but

even more impressed with their obsession with violence. I

said nothing about "perversities," or about "turning

your stomach," or about "weird plots."

The

book: "Lieber said recently that A.B. Magill, who

had provided information on Chambers to the Hiss defense,

was the representative of the American Communist Party who

helped him make contacts

in Mexico with Eastern European embassies (Lieber and his

family, after several years in Mexico, settled in Poland)."

The

facts: I was not the representative of the American Communist

Party in Mexico. From 1950

to 1952 I was a correspondent there, first of The Daily

Worker and later of Telepress, a left-wing international

news agency that folded in the latter year. During two and

a half years in Mexico I was occasionally invited, as were

Mexican newsmen and women, to social functions at the Czech

and Polish Embassies. Maxim Lieber sought repatriation to

the country of his birth, Poland, and I may have introduced

him to a Polish Embassy official, though I have no specific

recollection of doing so. Lieber departed for Poland more

than two years after I left Mexico.

HOPE

HALE DAVIS

As

one who was a member of the Communist underground in Washington

from mid-1934 to early 1937, I find some of Victor Navasky's

quoted contradictions of statements from interviews by Allen

Weinstein in "Perjury" rather perplexing.

I

have known personally a number of the people whose denials

Navasky quotes. I would not expect

one of them, if confronted with a statement published in a

context unfavorable to them, to give an honest, unprevaricating

response. But the case of Katherine Perlo's letter to President

Roosevelt was even more puzzling.

Navasky

derides Weinstein as follows: "The Washington 'underground

Communist group,' headed

by Victor Perlo, was 'confirmed' when 'Katherine Wills Perlo

wrote an anonymous letter to the White House in 1944.'"

Here

Navasky seems to be doing something strange - suggesting that

Weinstein needed Mrs. Perlo's

letter to prove the existence of the underground, and that

anything shaky about the letter should shake any right-thinking

reader's belief that there ever had been a Washington Communist

underground.

He

proceeds then to find the letter shaky because Mrs. Perlo

was under the care of a psychiatrist,

and because she added the psychiatrist's name to those of

her husband and others she accused of a Communist conspiracy.

I

have no information about Mrs. Perlo's psychiatrist. For all

I know, he could have been a Communist.

Such a choice, if made by a comrade, would have been natural.

But about Victor Perlo himself and his underground activities

there can be no doubt. I attended a unit meeting (we did not

use the term cell) once a week for more than two years, and

Vic was present surely at more than seventy of them. He was

my first unit leader; how well I remember his kneeling one

night drawing a map of China with different colors of chalk

on a child's blackboard, while giving us a progress report

on the territory gained by Chu Teh, Chou En-lai, and Mao Tse-tung.

I

am not sure whether Katherine Wills Perlo is the wife I knew.

If she is, the marriage has an interesting

history. Vic was only 22 when I first met him in 1934. He

had been a mathematical prodigy, and was brilliant at his

job in the New Deal. But his development had been one-sided.

The more sophisticated comrades called him socially immature,

and a campaign was launched to help him try, as the rest of

us were doing, according to party directives, to play the

role of a proper bourgeois adult. Always an earnest and literal-minded

adherent to party decisions, Vic appeared, within weeks, proudly

leading a blonde bride. He established her in a little country

house and even produced a baby. Vic's wife never seemed a

natural as a Communist, and I am not surprised, if this Mrs.

Perlo is the same woman, that she became fed up with the party

and its demands.

But

whoever she was, whatever her mental condition in 1944, however

she phrased her accusation, the Washington underground not

only existed but was used, to my knowledge, for stealing documents

from government agencies. I myself carried out such an assignment,

admittedly a harmless one for I had no access to secret information,

but performed by means of stealthy, illicit entry and the

rifling of an official's files, for practice. But my husband,

whose breakdown and death may have been due to the conflicts

caused by his conspiratorial activities, was leader of one

of the most productive of the five-member units that made

up our part of Hal Ware's group. He himself regularly went

to the New York waterfront to give a party contact confidential

information from his job in the shipping division of the labor

board of NRA, later of the National Labor Relations Board.

Everyone in Hal Ware's group had accepted the directive to

get whatever we could for the party to use in any way it saw

fit.

Note

from Victor Navasky:

What

appears above is a second draft. When Hope Hale Davis called

to ask whether we were printing her letter I assured her we

were, but observed that she had misconstrued my point, which

had to do only with Weinstein's deficiencies as a scholar.

In a footnote on p. 22 of "Perjury" he refers to

an anonymous letter sent by Mrs. Perlo "to the FBI"

which accused her husband of "espionage." In fact

the letter was sent to the President and said nothing about

espionage. On hearing this, Hope Hale Davis said, "Oh,

I forgot to put in the espionage part," and a few days

later her addendum arrived with the final paragraph amended

to include the espionage part.

If

Davis is accurate in her memory, however, she has provided

further evidence of "Perjury's" carelessness, for

Weinstein neglected to include her name along with others

he listed as members of the Perlo and Ware groups.

HELEN

L. BUTTENWIESER

I

have read with interest the account of your efforts to verify,

at Mr. Weinstein's invitation, his quotes or summaries of

certain taped interviews.

Your

experience comes as no surprise to me, as my reading of the

book (I have only been able to struggle through half if it

so far) indicated clearly that, while posing as a scholar

whose search has revealed hitherto unknown facts, Mr. Weinstein

has merely taken existing material, and by clever use of the

English language makes every correction of prior testimony

by Alger Hiss sound as if he had been forced to retract a

lie while at the same time misquoting Whittaker Chambers so

that subsequent changes would not appear to be changes at

all.

I

refer you for instance to page 47 where Weinstein says that

". . . Hiss adjusted his testimony . . ." whereas

in his portrayal of Whittaker Chambers he not only plays down

changes (see page 19) but in one striking instance actually

misquotes Chambers on a vital point, so that no later correction

will be necessary. I refer in this instance to Chambers's

testimony before HUAC, commencing with a prepared statement

on August 3, 1948 and repeated frequently until he found it

necessary to change his story toward the end of August 1948.

(See page 5 where Mr. Weinstein writes that Chambers said

he left the party in 1938 whereas in fact, Mr. Chambers said

he left the party late in 1937.) This of course, is a crucial

"correction" of the facts by the author, since assuming

Mr. Chambers was correct when he said that he left the party

in late 1937, the documents he produced dated February and

March 1938 could not have come from Alger Hiss.

However,

annoying as I find Mr. Weinstein's deliberate manipulation

of the reader's impression of the respective truthfulness

of Mr. Hiss and Mr. Chambers, I am even more put out by his

unscholarly habit of appearing to append verification of an

otherwise unsupported statement referring the reader to a

footnote at the back of the book which, when consulted, fails

to confirm the statement footnoted: page 186, footnote 63;

page 194, footnote 81; page 196, footnote 1; page 197, footnote

3; page 215, footnote 41; page 319, footnote 27.

These

are but some of the defects I picked up, having neither the

time nor the patience to check each footnote, but even these

discrepancies are sufficient to give "the lie" to

the current propaganda that Mr. Weinstein, through his outstanding

scholarly efforts, has finally "proven" that Alger

Hiss is guilty.

PHILIP

NOBILE

I

felt an eerie sense of deja vu when I read in The

Nation that Allen Weinstein reneged on his promise, even

dare, to have Victor Navasky inspect his "Perjury"

archives. Apparently, Weinstein didn't have the nerve

to turn away Navasky himself and had his wife perform this

graceless task at the door of their Washington home. I consider

this breach of a promise, made with great bravado on television,

a mark of dishonor. It raises the question whether such a

man can write honest history. For I don't think an historian's

character is unrelated to his product. For example, Weinstein

despises personal contretemps. He is extremely uncomfortable

in situations, private or public, where he is strongly challenged.

In other words, he has a difficult time coping with unpleasantness.

This personality trait would be of no matter in a medieval

historian, but it hurt Weinstein's research immensely. His

fear of confrontation prevented him from presenting evidence

to principals in the Hiss case. I was with him when he told

Alger Hiss in his last interview that he thought Hiss was

guilty. Although extremely nervous, Weinstein went on to say

that he possessed documentary evidence proving Hiss had lied

when he said that he had no independent recollection of the

whereabouts of the Woodstock typewriter. But did Weinstein

show the accused his documentary evidence as any cub reporter

would have done? No. Nor did he have the courage to face Mrs.

Hiss with an allegedly incriminating letter. Nor did he allow

Donald Hiss to comment on his alleged role in hiding the Woodstock

typewriter from the FBI. Weinstein constantly wraps himself

in the nonpartisan mantle of an objective historian. Yet he

failed at crucial times to let the witnesses to history speak

in his book. Why? I repeat, it's a matter of character. How

can I make these statements? I was once Weinstein's friend.

My feeling of deja-vu relates to another betrayal of

promise that likewise bears on the question whether Weinstein

can write honest history.

My

story is a footnote to "Perjury." My dispute

with Weinstein has nothing to do with Hiss's guilt or innocence.

It is irrelevant to history, but I judge not to the current

imbroglio regarding Weinstein's methods that is his reliability

as an historian. As I wrote Weinstein recently, I happen to

believe in the book if not in you. I would not write those

words today even though I think Hiss is guilty.

It

would take more space than it is worth to give the full story

of the dealings between Weinstein and myself on the news rights

to "Perjury" which persuade me that his character

must be an element in anyone's judgment of his work on the

Hiss case. Weinstein had given me exclusive news rights to

the discoveries he claims to have made in the course of his

research for his book. I was to make them public in a long

prepublication interview.

Weinstein

reneged on this verbal contract. I had, with Weinstein's approval,

arranged for the exclusive interview to appear in Politicks

six weeks before the book's publication date. After I

made this deal known to Weinstein, he allowed his agent to

sell the news rights to Time without so much as telling

me or Tom Morgan, editor of Politicks. The handling

of this matter is now before the Ethics Committee of the Society

of Authors' Representatives at my instigation.

When

I faced Weinstein with this betrayal he offered to send me

a check from his Time fee to compensate for my small

Politicks payment and said he would make amends to

Politicks. Knopf is going to hate me for this

by calling a press conference in its offices to answer any

and all questions regarding "Perjury." I

declined the former and Morgan the latter. Weinstein thought

he could cover his dishonor with a check and some publicity.

He concluded by saying that he hoped he could salvage our

friendship and would come up for dinner the following night.

As with Navasky, he never showed.

And

so I come back to my original question. Can such a man write

honest history? I'm not sure. Navasky demonstrated that Weinstein

has fiddled with evidence, overstated facts and covered up

ambiguities in order to fit his view of the case. I see certain

parallels in Weinstein's personal behavior. And so I would

not be surprised if the character that broke promises both

to Navasky and me, when it suited his purposes, also betrayed

history in "Perjury" where it suited his

purposes.

Back

to the Book Review Section Back

to the Book Review Section

|