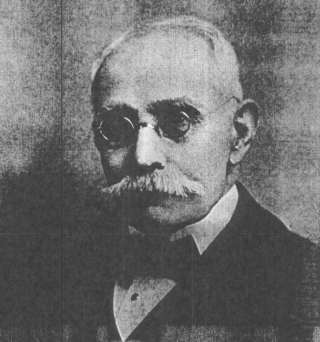

Ferrandini, Cipriano (1823-1910)

MSA SC 3520-14473Barber

Cipriano Ferrandini was a hairdresser from Corsica who emigrated to Baltimore, and established himself as the long-time barber and hairdresser in the basement of Barnum's Hotel. There he practiced his trade from the mid 1850s to his retirement long after the close of the Civil War. He was accused, but never indicted for plotting to assassinate Abraham Lincoln on February 23, 1861, and while once caught in a secessionist dragnet in 1862, was never prosecuted for his pro-Southern convictions.

How do you discern bravado and bar room talk from a serious threat to personal safety? How do you confirm and abort a terrorist threat?

Those were likely questions that the President Elect of the United States, Abraham Lincoln, pondered the nights of February 21st and 22nd, 1861, when Allen Pinkerton, a detective he trusted, and Frederick Seward, son of his greatest Republican Rival and soon to be Secretary of State, warned him that he ought not to appear in public in Baltimore as scheduled because plans were afoot to assassinate him.

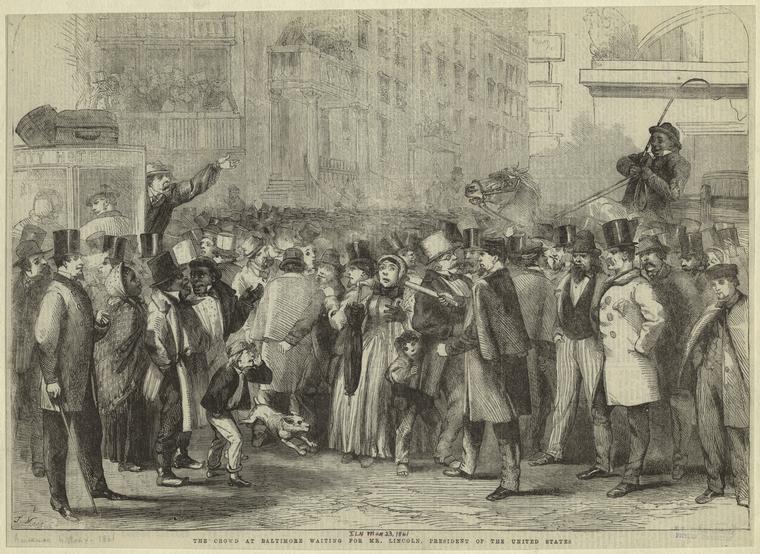

Lincoln chose to heed the warning, donned a disguise of a soft cap, and passed through Baltimore unseen and unheralded on the night of the 22nd, leaving Mrs. Lincoln and the children to face the crowd awaiting his arrival from Harrisburg the following day, February 23.

From that day forward, historians have argued over whether or not there

was a plot and in the course of their narratives have not only created

myths and perpetrated fallacies, but also have missed a few clues.

Historians fall into two main camps.

There are those who follow the lead of John Thomas Scharf, who had dual careers with the Confederate Navy and Army. He went to great lengths to argue that Baltimoreans would never do anything so ignoble, even though the cause was just. According to Scharf, who spilled more ink than any historian in denial, there simply was no evidence of a plot and after all no one was ever arrested for even contemplating one, although many other good citizens were thrown into jail without benefit of habeas corpus.

The other camp is led by the carefully considered research of William Evitts, who in A Matter of Allegiances based his arguments in favor of their being such a plot on the papers of Allan Pinkerton which the Huntington Library acquired, and which Norma B. Cuthbert edited for publication in 1949. Scharf denied that there were any names associated with the plot. Professor Evitts used Pinkerton's papers (of which the Huntington Library only had transcripts made by Lincoln's friend and biographer William Herndon--the originals apparently were lost in the Chicago Fire) to name Cipriano Ferrandini, a Baltimore hairdresser/barber as the Captain of the terrorists. Professor Evitts found the Pinkerton evidence convincing, and other historians, like Robert Brugger, have accepted his conclusions, even though they do not mention Ferrandini by name.

Who was Cipriano Ferrandini? What facts can we glean about his life before attempting to evaluate the level of threat, if any, that he posed against the life of Abraham Lincoln?

Because there is a project at the Maryland State Archives to bring all extant vital records in Maryland on line, research began with the end to see if there were any records of anyone with such a distinctive name who died in Maryland. Two were found, father and son.

The father, Cipriano Ferrandini died at the age of 87 in the rented house of his daughter and son-in-law on Radnor Avenue, Govans, a Baltimore suburb, in 1910, ironically as a result of botched dental work, by a professional dentist, the successor in profession to barbers who generations before extracted teeth and acted as itinerant surgeons. Cipriano's son and namesake bought a house only a few blocks away on Willow Avenue, which has since been demolished for the grounds of the Carter Elementary School.

Fortunately Cipriano died at the end of a census year, so his presence in Maryland could be traced backwards decade by decade using census schedules on Ancestry.com which provides all the extant census records accompanied by more or less helpful indexes.

In the census records, the spelling of Cipriano Ferrandini is erratic, which made the hunt much more difficult.

His name is spelled:

Siprono Fernandini in 1910

Sip Ferrandine in 1900

Cipri Ferrandini in 1880

Ciprian Ferrendinie in 1870

Cipri Ferrandini in 1850

Note that there appears to be no census record for 1860. There is good reason, possibly related to the plot.

From the eve of the Civil War until his first wife Harriet died about

1872 in a terrible accident reported as far away as New York, Cipriano

and his family lived in a house his wife owned at what would today be

1608 East Baltimore Street.

Great detail could be given about her ownership and his stewardship of

this property, but suffice it to say that tracing the mortgages through

our new on line service of all Land Records, makes it clear that the

property was used for home equity loans. Every few years as they paid

off one mortgage they took out another, on average every six years from

1858 until Harriet's death, when Cipriano remarried a woman 21 years

his junior and moved to Madison Street.. Of all the mortgages, the

first is the most interesting. In 1858, Cipriano borrowed $2,000 on his

wife's house from Thomas Winans, a mortgage that was not released until

1869 when Winans was in Russia building locomotives. In 1861, Thomas

Winans and his father Ross, would be outspoken secessionists, possibly

even aiders and abettors of an effort to invent and raise arms against

the North, if not directly involved in plotting murder.

But was Cipriano really a terrorist bent on assassinating President Elect Lincoln in February 1861?

First let's get the facts straight about what happened that day, because accounts are conflicting.

As best as can be determined, The New York Times got it

wrong and John Thomas Scharf got it right about the sequence of events

on February 23, 1861. Lincoln did, of course, move through town in

secret. That is a given. But the details surrounding how Mrs. Lincoln

and the children were guarded have been overlooked in the partisan

arguments over the plot. Marshall Kane did have a plan and it was

implemented. Mrs. Lincoln and the Children did not arrive at the

Calvert Street Station to be greeted by a hostile crowd. There was a

hostile crowd there alright, as the New York Times correspondent

pointed out, but Mrs. Lincoln and the children were let out of the

train where the tracks crossed Charles Street above the Washington

Monument and were whisked to Democrat John Gittings mansion on Mount

Vernon Square, where they were treated to a quiet, private dinner,

before being taken to Camden Station much later that afternoon. Whether

or not they encountered some unpleasantness at Camden Station is a

matter of debate, but Lincoln did not abandon his family to an

unprotected journey through a raucous Baltimore. Marshall Kane,

Southern sympathizer and future Confederate businessman who may have

met with John Wilkes Booth in Canada in 1864, did his job well on

behalf of Mary Todd and the children.

Probably one of the funniest contemporary theories why Lincoln really

avoided Baltimore, was to not have to meet with his small but zealous

contingent of Republican supporters, but what about the plot? Was there

one and was Cipriano Ferrandini at its head?

First, there is the Pinkerton evidence.

The only purported contemporary account of Pinkerton and his spies is

the transcript of his 1861 journal which he let Herndon copy and which

was purchased by Ward Hill Lamon, Lincoln's body guard. The Cuthbert

book makes it very clear that Ward Hill Lamon had little use for

Pinkerton and the feeling was mutual, leading Lamon to at one point

discount the existence of any plot, but if the transcript of

Pinkerton's 1861 Journal can be authenticated in any way, perhaps the

old saw, where there is smoke there is fire, may prevail.

Pinkerton's account relies upon one agent and two sources to document

Cipriano Ferrandini as the leader of the assassination plot. His agent

meets with Cipriano and leaves a vivid account of the extent of the

plot as derived from a participant who related the details from the

comfort of a Davis Street bawdy house and the arms of an inmate named

Annette Travis. She did exist and is listed on the 1860 census for

Baltimore at #70 Davis Street. Davis street ran south from the Calvert

Street train station and appears to have a number of such places in the

11th ward, forming one of the more concentrated 'red light' districts

of the city. In his Spy of the Rebellion

(1883), p. 64-65, Pinkerton asserts that in addition to his spy Howard,

he also met with Captain Ferrandini (who he calls Fernandina), at Guy's

Monument Hotel, which was across the street from Barnum's on Monument

Square.

At Guy's, Pinkerton reports that "Fernandina cordially grasped my

hand, and we all retired to a private saloon, where after ordering the

necessary drinks and cigars, the conversation" turned to the

assassination and Ferrandini was asked "Are there no other means of

saving the South except by assassination?" "No replied Fernandina, ...

He must die -- and die he shall, And, ... if necessary, we will die

together." To illustrate his story, Pinkerton included a drawing of

himself seated at a table with Ferrandini standing, hand upraised as if

clutching a dagger.

But does any of this prove that there was a National Volunteers

group led by Cipriano Ferrandini deeply immersed in a plot to

assassinate the President Elect? Pinkerton himself began to doubt the

bravado of his prime suspect, or at least so he says long after the

fact, but Cipriano himself leaves us with some clues (if the Congressional Record can be trusted).

Eighteen days before the alleged timing of the terrorist attack on

Lincoln, Cipriano Ferrandini appeared before a Congressional Committee

of Five investigating rumors that efforts would be made to prevent the

President Elect from reaching his inaugural, or if he did manage to get

to Washington, seriously disrupt the ceremonies. The committee had been

formed at the end of January when the Union appeared to be rapidly

dissolving. Efforts at brokering a compromise were floundering. Even

Lucius E. Crittenden recalled that on hearing the news that Lincoln had

indeed made it to Washington, a Missouri colleague at the Washington

Peace Conference exclaimed: "How the devil did he get through

Baltimore?" Crittenden speculated that clearly more than Italian (did

he mean Corsican?) assassins and plug uglies must have known of the

plots to keep Lincoln from being inaugurated. If the upper levels of

Baltimore and Washington society knew of any such plot, they probably

learned about it at the Maryland Club. As Robert Brugger discovered, in

July 1860, a Colonel Cipriani from Corsica dined at the club as a guest

of J. N. Bonaparte, Napoleon's nephew. Was this a cover for Captain

Cipriano Ferrandini recently returned from terrorist training in

Mexico? The Maryland Club was clearly a hotbed of Southern sympathy,

and had a remarkable guest list of Rebels and Copperheads, until closed

down by Union Troops.

Just what did Ferrandini have to say for himself to the Committee of

Five the following February? For one he suggests that the reason he

could not be found when the 1860 census was taken was because he was in

Mexico in military training. For another he certainly makes his

secessionists views very clear and has no problems admitting that he is

engaged in applying his military training to a group dedicated to

preventing the "Northern Volunteers" from passing through Maryland.

From the Congressional Record, you can get a flavor of the passion of

this 38 year old Corsican Barber. Can you see him acting on that

passion? Was he all talk? Was there a plot? He certainly traveled in

the circles that cried out for Maryland to secede. His mortgage was

held by one of the town's purported leading southern sympathizers. Was

the potential for violence defused by the steps taken on the advice of

Pinkerton and derived from a profile of Ferrandino that he himself drew

before a Congressional Committee?

Cipriano Ferrandini died an old man with terrible teeth, in the care

of his family. Did he plot to assassinate Lincoln? Probably. Would he

have carried out his threat if Lincoln had stopped in Baltimore as

planned? Or is it possible that he became a Union informer and a useful

means of persuading Lincoln to avoid the City at a time when Lincoln's

safety could not, in the minds of his closest advisers be guaranteed?

Edward C. Papenfuse, Maryland State Archivist