A COURT OF APPEALS TIME CAPSULE:

SIX HISTORIC ARGUMENTS IN THE NATION'S OLDEST APPELLATE

COURT

![Interior of Court of Appeals, ca. 1860s [MSA SC 182-90], i002957a](../images/i002957a.jpg) Journey

back to the early part of the 19th Century -- 1821 to be exact. The Court

is presently composed of six appointed judges who were also trial judges.

It has been located in a room in the State House

for some 40 years, although the Court also sits on the Eastern Shore. We

believe the judges wore robes, but they probably did not have an elevated

bench. The room looks very much like a trial courtroom. There was no limit

on the length of oral argument. It would not be until 1826, that the Court

would fix a six-hour limit on arguments on the Western Shore. Arguments

by members -- of what was probably a genuine appellate bar--could run for

days and were marked by dramatic performance, flights of eloquence, learned

allusions and, given their length, a great deal of tedium.

Journey

back to the early part of the 19th Century -- 1821 to be exact. The Court

is presently composed of six appointed judges who were also trial judges.

It has been located in a room in the State House

for some 40 years, although the Court also sits on the Eastern Shore. We

believe the judges wore robes, but they probably did not have an elevated

bench. The room looks very much like a trial courtroom. There was no limit

on the length of oral argument. It would not be until 1826, that the Court

would fix a six-hour limit on arguments on the Western Shore. Arguments

by members -- of what was probably a genuine appellate bar--could run for

days and were marked by dramatic performance, flights of eloquence, learned

allusions and, given their length, a great deal of tedium.

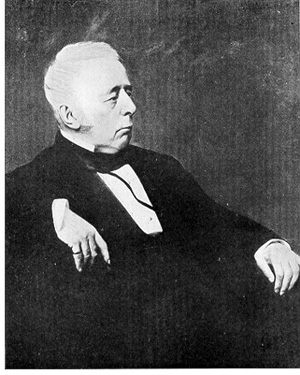

![Luther Martin, Rosenthal Engravings [MSA SC 2221-1-24], i003005a](../images/i003005a.jpg) Our

first argument combines two well-known components of Maryland legal history

- banking scandals like those experienced in the State in the 1960s and

1980s and Luther Martin -- venerable Attorney General, distinguished delegate

to the Constitutional Convention, "the bulldog of federalism", "Lawyer

Brandy Bottle"; and early-American super-lawyer.

Our

first argument combines two well-known components of Maryland legal history

- banking scandals like those experienced in the State in the 1960s and

1980s and Luther Martin -- venerable Attorney General, distinguished delegate

to the Constitutional Convention, "the bulldog of federalism", "Lawyer

Brandy Bottle"; and early-American super-lawyer.

Toward the end of his long career, Martin, much like Ahab and the whale,

became obsessed with the evils of the National Bank. He argued in the Supreme

Court and lost

McCulloch v. Maryland, which held that the State

could not tax a branch of the United States Bank. Undeterred, in the State

v. Buchanan, Martin continued his assault. But his was not a frivolous

obsession. When Bank officers, James Buchanan, George Williams and James

McCulloch wanted money from the bank, they simply took it without giving

security or bothering to inform the Bank's directors. Martin sought to

indict them -- charging a conspiracy to defraud and impoverish the Bank.

While making the criminal presentments, Martin suffered a disabling stroke.

The case moved forward, but upon a demurrer of the defendants, two judges

of the County Court of Harford County (over

a dissent) dismissed the case, apparently concluding that the indictment

charged no crime and that the State court had no jurisdiction. The State

appealed.

Despite the confusion of the official reports in the Court of Appeals,

the defendants were represented by Daniel Raymond and William

Pinkney. The State was represented primarily by Henry M. Murray and

Robert

Goodloe Harper. Also involved in the case was U.S.

Attorney General William Wirt, who was specially admitted after taking

the required oath "declaring his belief in the Christian religion". We

will hear from Murray and Raymond.

*****************************

THE STATE V. BUCHANAN

Henry M. Murray for Appellant:

The first count of the indictment charges the Defendants, Mr. Williams,

Mr. Buchanan and Mr. McCulloh with an executed conspiracy -- falsely, fraudulently,

and unlawfully, by wrongful and indirect means, to cheat, defraud and impoverish

the President, Directors and the Company of the Bank of the United States.

These three men conspired together to obtain and embezzle a large amount

of money and promissory notes for the payment of money, commonly called

bank notes, the entire sum having a value of Fifteen Hundred Thousand Dollars

in United States currency. This money was the property of the President,

Directors, and Company of the Bank of the United States. It came out of

the office of discount and deposit of the Bank in the City of Baltimore,

the very office where Buchanan was president and McCulloh was the cashier,

without the knowledge or consent of the President, Directors, or Company

of the Bank of the United States.

The purpose of the conspiracy was to have and enjoy the money of the

Bank for a long space of time -- two months -- without paying any interest

or other sum and without securing the repaying of the money. In furtherance

of this scheme, James W. McCulloh, the cashier of the office of discount

and deposit, would falsely and fraudulently state and represent to the

directors of the office of discount and deposit that the monies and promissory

notes that were loaned had sufficient and ample security -- the capital

stock of the Bank. Williams, Buchanan and McCulloh carried out the scheme

in abuse and violation of their duty and in violation of the trust reposited

in them as officer of the Bank.

It is not open to question that the matters charged in the indictment

amount to an offense that could be prosecuted as crime. Conspiracy is a

crime and an offense at common law. The gravamen of the offense consists

of the unlawful combination or confederacy to injure a third person. The

State does not have to show actual execution of that unlawful or wrongful

purpose. This was clearly the law of England. But when our ancestors came

to this land and they settled the colony of Maryland they brought the common

law of England with them as part of their birth right. The law of conspiracy

was part of that law and it remains in full force here today as it was

in England then. So the act of criminal conspiracy should be recognized

by the courts of this State as it has already been recognized by other

states in the United States.

Now the Defendants argue that Maryland courts cannot hear the case because

the charges refer to the Bank of the United States. Nothing in Art.

III §2 of the Constitution requires the case to be filed in a United

States court. The Ninth Amendment states that "The enumeration in the Constitution,

of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained

by the People." The Tenth Amendment says that "The powers not delegated

to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States,

are reserved to the States." So therefore, the State of Maryland has retained

the power to have these charges heard in its courts.

Daniel Raymond for Appellees:

Your honors, the indictment below was properly dismissed. The statute

33 Edward §1 is the origin of the Law of Conspiracy. This statute

does not include conspiracies to cheat.

Cheating itself, with one of two exceptions like cheating with false

weights, false measures or false dice, is not an offense that is punishable

at common law. It would therefore be an absurdity to punish an agreement

to cheat, when cheating itself is not punishable by the State.

Now the State has cited many, many cases either in argument or in submissions

to you. Almost all of those cases are conspiracies to do acts which are

themselves indictable. They have no application here. I am sure that in

those many, many cases you might find a few of a different character, that

are from doubtful authority, from which one might weave together a principle

of law that is just absurd on its face -- that you can be indicted for

conspiracy to do something that in and of itself you cannot be indicted

for. Those questionable cases do not justify a reversal here.

The State also contends that our ancestors brought with them the common

law of England, and that that law as it sees it must be taken as established

at the time of their emigration. Even if that is so, the common law in

England at the time was that a conspiracy is not a crime unless it is to

do some act which is itself indictable.

In addition, the indictments were properly dismissed because even if

a naked agreement to cheat is indictable in this State, it must still be

an agreement to cheat some person or being known to the laws of the state

of Maryland. The Bank of the United States was created by a government

foreign to Maryland. The Bank was created under the laws of the United

States. An agreement of cheat the Bank of the United States

is no more an offense against the laws of Maryland, than an agreement to

cheat the Bank of England would be. So if this Court decides that

the matters charged in the indictments are offenses punishable as a crime,

the courts of this State still have no jurisdiction over the case. Such

a crime being perpetrated against an entity created by the United States

is only cognizable in the Courts of the United States under Article III,

Sections 1 and 2 of the Constitution.

*****************************

![Judge John Buchanan [MSA SC 1545-1155], i002983a](../images/i002983a.jpg) In

1821, the Court reversed the dismissal of the indictment. Judge John Buchanan

(no relation to the Bank officer), in a lengthy opinion, noted that Maryland

had inherited the English common law on conspiracy and that the offenses

were indictable even if nothing had been done in execution of the conspiracy.

The Court also held that the matters charged were not a crime against the

United States, but a common law offense against the State of Maryland.

Finally, Judge Buchanan said:

In

1821, the Court reversed the dismissal of the indictment. Judge John Buchanan

(no relation to the Bank officer), in a lengthy opinion, noted that Maryland

had inherited the English common law on conspiracy and that the offenses

were indictable even if nothing had been done in execution of the conspiracy.

The Court also held that the matters charged were not a crime against the

United States, but a common law offense against the State of Maryland.

Finally, Judge Buchanan said:

It may be admitted, that the Legislature of the State has no right to

pass laws calculated to control or impede the operations of the bank. But

it is difficult to imagine, how a general power in the judicial tribunals

of the State, to punish an offence against the State, can be considered

as an unconstitutional interference with the concerns of the Bank of the

United States, or in any manner endangering its security, only because

its officers happened to be the objects of the prosecution....

Despite the State's victory in the Court of Appeals, the scoundrels

eventually prevailed. Buchanan and McCulloch were later tried in Harford

County and acquitted by the same 2-1 vote that marked the initial decision.

Subsequently, Williams was acquitted, because by himself he no longer could

be found guilty of a conspiracy.

Martin never recovered from his stoke. He moved to New York to be cared

for by one of his former clients -- Aaron Burr. He died in 1826.

*****************************

In 1860, the Court still occupied its traditional quarters in the State

House. But a great deal had changed. As a result of the Reform Constitution

of 1851, judges (who were now called "justices") were elected. To protest

the change, the entire membership of the Court declined to run for election.

In addition, the Court of Appeals now consisted of only four judges. Bowing

in 1828 to Jacksonian democracy, judges no longer wore distinctive dress.

And the Constitution now required written opinions.

*****************************

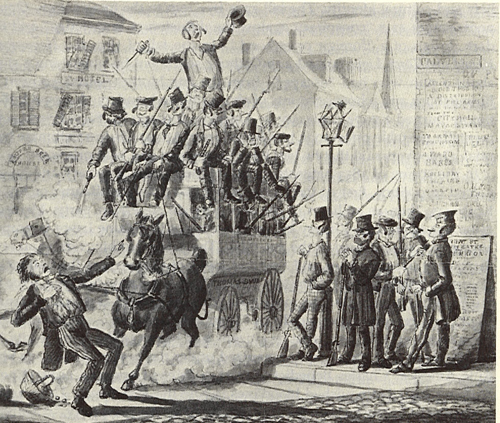

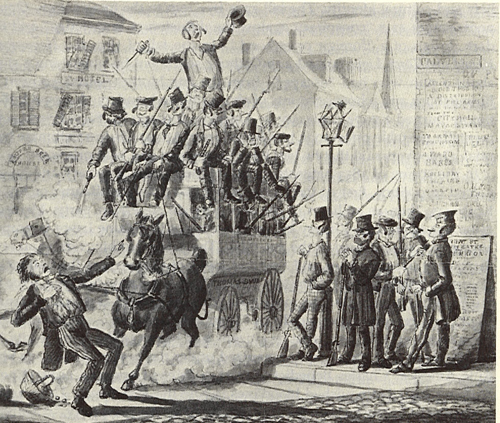

But

bigger changes were taking place in the State. Recurrent election day violence

in Baltimore City by members of the Know Nothing Party had won for the

City the unenviable title of "Mobtown." Roving

gangs with blood-curdling names such as the "Rip Raps", the "Plug

Uglies" and the "Blood Tubs" "cooped up" drunks and led them to cast

multiple votes for their own party, while intimidating the opposition from

voting with bullets, brawn and mayhem -- oftentimes with the assistance

or sufferance of City Police officers.

But

bigger changes were taking place in the State. Recurrent election day violence

in Baltimore City by members of the Know Nothing Party had won for the

City the unenviable title of "Mobtown." Roving

gangs with blood-curdling names such as the "Rip Raps", the "Plug

Uglies" and the "Blood Tubs" "cooped up" drunks and led them to cast

multiple votes for their own party, while intimidating the opposition from

voting with bullets, brawn and mayhem -- oftentimes with the assistance

or sufferance of City Police officers.

In 1860 legislation came before the General Assembly to curtail such

acts of lawlessness by creating a four-member Police Board of Baltimore

City. Unable to kill the bill on the merits, the Know Nothings piled on

obnoxious amendments such as one banning "Black Republicans" or "endorsers

or supporters of the Helper Book, " an anti-slavery tract, from serving

on the new Board. Nevertheless the bill was enacted and was immediately

challenged by the City, which contended that its charter was a constitutional

one that could not be diminished by the transfer of control of the City

Police; that only the Governor, not the General Assembly, could control

appointments to the Board; and that the "Black Republican" disqualification

was unconstitutional and not severable from the remainder of the Act. Following

a loss in the Superior Court, the City appealed.

Within weeks the case was before the Court of Appeals. Arguing for the

City was Thomas Alexander. Among those arguing for affirmance was legal

legend Reverdy Johnson.

*****************************

BALTIMORE CITY V. STATE

Thomas S. Alexander for Appellants:

In the late session, the General Assembly of this State passed an Act

for the purpose of repealing the powers of the Mayor and City Council of

Baltimore to establish and regulate a police force, and in place of that

power providing a permanent police for the City of Baltimore. The chartered

rights of a large, prosperous city have been invaded by a legislative enactment

which has no warrant in the Constitution.

The Constitution does not confer upon the Legislature the power to appoint

members of the Police Board. Appointment to office is peculiarly an executive,

not legislative, power. Section 11 of Article 2 of the Constitution gives

the Legislature, in creating an office, power only to prescribe the

mode

of appointment. This can, by no legitimate manner of construction,

be interpreted to grant the power of legislative appointment.

The Act transfers the whole existing police force of the City of Baltimore

-- officers and men -- from the city government to the Commissioners. That

is unconstitutional and illegal. The charter of 1796, in giving to Baltimore

a local government, by unavoidable implication gave all the means necessary

for the purpose of government, among which was a police power to maintain

the peace and security of the governed. This is an inherent right, co-existent

with the government, and cannot be separated from it. If the Legislature

has no power to repeal the charter of 1796, it also has no power to dismember

the government created by it, by annulling and destroying important and

indispensable powers.

It is further provided by section 6 of the Act, "that no Black Republican

... shall be appointed to any office under said Board." The prohibition

of the Black Republican introduces into our legislation the broad principle

of proscription for the sake of political opinion.

The invaluable birthright of every freeman is that he may express at

pleasure his opinions on all subjects of public policy, restrained only

by positive enactment to the contrary.

If a Legislature in former days had proscribed the Roman Catholic or

the naturalized citizen, it is presumed this court would have no difficulty

in pronouncing against the constitutionality of the provision. In principle

the proscription is the same. In degree the difference is that whilst the

test of religion or of birth is susceptible of evidence, the test created

by the Police Bill rests in the pleasure of the Police Board. What is Black

Republicanism? A Black Republican may be defined to be one who thinks the

area of slavery out not to be enlarged. Again, he may be defined to be

one who thinks Congress has power to legislate over the subject of slavery

in the territories. It is certain that in the letter of the proscription

there is an elasticity which will, with willing minds, justify its expansion

over two-thirds of the population of Baltimore.

If this disqualifying clause is an operative part of the Act, the whole

Act must be pronounced unconstitutional.

Reverdy Johnson for Appellees:

The

questions regarding the judgment of the court below fall under two heads:

the first relating to the authority of the Legislature to create a Board

of Police and to appoint its members; and the second relating to the powers

conferred on the Board.

The

questions regarding the judgment of the court below fall under two heads:

the first relating to the authority of the Legislature to create a Board

of Police and to appoint its members; and the second relating to the powers

conferred on the Board.

As to the ability of the General Assembly to create and fill an office,

it is sufficient to refer to Article 2, Section 11 of the Constitution

which provides that the governor shall nominate and, by and with the advice

and consent of the Senate appoint, all civil and military officers of the

State whose appointment or election is not otherwise provided for "unless

a different mode of appointment be prescribed by the law creating the office."

The

power of appointment to office is not, under our form of government, a

purely and inherently executive function.

The City of Baltimore maintains that because the Constitution recognizes

the city as part and parcel of the organized government of the State, its

charter is therefore placed beyond the power of the Legislature to modify

or change it. Yet it will hardly be pretended that it is beyond the power

of the Legislature to enlarge the limits of the city, by bringing portions

of the county within its borders, or to confer upon the city authorities

the discharge of other duties than those they now possess. Such has never

been the construction of the Constitution. The charter of the city, from

the day of its passage to the present, has constantly been subject to alteration

and amendment by the Legislature, and the inconveniences which would result

from now placing it beyond the power of such alteration and amendment are

so obvious that they need not be pressed. Nothing but plain and explicit

language in the Constitution could effect such a result. Such language

cannot be found in that instrument. It is clear that the people when they

adopted the Constitution never supposed they were parting with the power

to govern and control the City of Baltimore, and to pass such laws as they

might deem the public good required to meet the constantly changing and

increasing necessities of its population.

An objection is raised to the proviso that "no Black Republican, or

endorser or supporter of the Helper Book, shall be appointed to any office

under said Board." It is said that this proviso proscribes persons for

the sake of their political opinions. But, if such proscription was designed,

it is totally at variance with the other provision of the law which requires

the Commissioners to take an oath that they will not appoint any person

to, or remove any person from any office under "on account of his political

opinion." It is a provision interjected into the Act repugnant to its whole

scope and object, and if it imposes a disqualification for office not sanctioned

by the Constitution, it will be stricken from the law without impairing

the efficiency of the other parts of the law.

*****************************

As quickly as the case arrived in the Court of Appeals, it concluded.

The justices had little trouble upholding the law, reasoning that the City

was a creature of the State and that the Governor had no exclusive power

to appoint that was infringed by the Police Reform Act. As to the "Black

Republican" qualification for office, the Court's opinion stated that "we

cannot understand, officially, who are meant to be affected by the provision

and therefore cannot express a judicial opinion on the question." Thus,

this particular confrontation between City and State ended and order was

restored on City election days. Of course, as a result of a series of later

General Assembly enactments, the City regained control over its police

force. However to this day, the City Police is by law a "state" agency.

It would not be the last time the General Assembly would transfer a major

function from the City to the State. With varying degrees of City consent,

in the 1990s the jail and the local board of education were made subject

to State control.

*****************************

It is nearly 50 years later. The Court survived the Civil War and two

more Constitutional Conventions. But a great deal had changed. There was

no longer a special appellate bar and lawyers no longer wore long black

coats and high silk hats. More elaborate briefs were required. Arguments

were shorter and no longer sprinkled with classical allusions. "Justices"

became "judges" again. By 1914, the judges would return to ceremonial dress

-- black silken gowns. Most importantly in 1903, after 122 years, the eight

judges of the Court moved out of the State House into a new Courtroom on

State Circle. One reason for the move -- the need to house an expanding

State law library -- suggested the increasing complexity of the 20th century

legal scene.

![Court of Appeals building, ca. 1903 [MSA SC 1754-2-124], i002977a](../images/i002977a.jpg)

*****************************

Our next case appears to be a small one. The Plaintiffs recovered a

one-cent judgment against the State. Naturally the Government appealed.

But appearances are deceiving and the eventual influence of the decision

is immense. Ironically, it involved a dispute over a portion of "Great

Constitution" Street in Baltimore City. The road bed was owned by the Gibsons

and on this property the State without their consent built an extension

of the Maryland Penitentiary. The Gibsons sued

John Weyler, the warden of the institution in ejectment. Weyler, the user,

not the taker of the property raised the defense of sovereign immunity.

Judge Alfred Niles rejected the defense and ordered judgment for the Plaintiffs,

including a nominal damage award. On appeal, Weyler was represented by

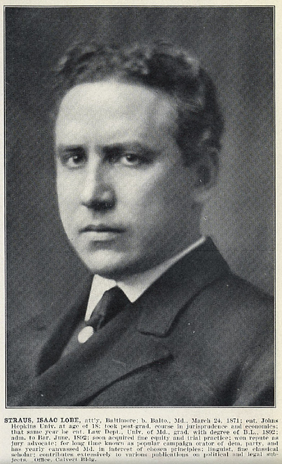

Attorney General Issac Lobe Strauss and the Gibsons by Frederick Fletcher.

*****************************

WEYLER V. GIBSON

Attorney

General Issac Lobe Strauss for Appellant:

Attorney

General Issac Lobe Strauss for Appellant:

The State of Maryland may not be sued in this matter directly, nor indirectly

through the Warden of its Penitentiary. The State, without its assent,

cannot be impeded and ousted by its own courts from the possession and

management of its institutions and property while discharging its public

duties owed to the people composing our State. This is a firmly settled

principle of law and public policy, supported by a legion of case authorities.

I would note further to this Honorable Court that Warden Weyler, for

the purposes of an action in ejectment, is not the true tenant in possession

nor is he a true party claiming adversely to the appellees' interests.

The Warden is but a mere servant at will of the Directors of the Penitentiary.

The Directors, were they a named defendant here, could assert the immunity

of the State, as well as the equitable defense that the appellees should

not be heard in ejectment now when they stood by silently, resting on their

rights, while the State expended public monies to erect the enlarged prison

across Great Constitution Street. The Warden, however, as a mere functionary,

cannot personally assert such defenses. Appellees should not be permitted

to maneuver this suit to choose an opponent whose choice of weapons with

which to defend himself is so limited.

Finally, as the public closure of Great Constitution Street has not

been consummated in a complete legal sense by the Baltimore City authorities,

as appellees argued in the trial court, appellees are not entitled to maintain

an action in ejectment for land that legally remains impressed with a public

easement as a street. If appellees have any right to sue, it is to sue

the City and its Commissioners for opening (and apparently closing) Streets,

for completion of the abandonment process and for a determination as to

whether the value of their property interest is greater or lesser for having

the street closed and whether the value of any public benefit accruing

from closure would result in an assessment against appellees.

Frederick H. Fletcher for Appellees:

It cannot be, indeed it has not been, disputed that my clients, the

heirs of the late Governor Carroll and his wife, are lawfully the owners

of the fee of the road bed of Great Constitution Street. Likewise, it is

patent that the State, without my clients' permission and without compensation

being paid to them, has taken upon itself to appropriate that land for

use as part of the Maryland Penitentiary, thereby also denying to the public

the former use of the land for its dedicated public easement as a road.

Further, the State concedes, as it must, that its efforts to close Great

Constitution Street legally were incomplete and imperfect.

My clients have every right to maintain this suit in ejectment. It may

be argued that we are arrogant to ask any court to order the State to move

or remove a structure, built with considerable public tax revenues, that

is fifty-five feet tall with walls 3 feet thick. That, however, is not

necessarily our objective. We ask rather that the wrong committed against

my clients be remedied as the court sees fit.

Our Declaration of Rights declares that every man for any injury done

to him in his person or his property ought to have remedy by the course

of the law of the land, and that no man ought to be deprived of his property,

but by the judgment of his peers, or by the law of the land, and section

40, Article 3 of the Constitution prohibits the passing of any law authorizing

private property to be taken for public use, without just compensation

as agreed between the parties, or awarded by a jury, being first paid or

tendered to the party entitled to such compensation. Nor shall any State

deprive any person of his property without due process of law. Speaking

of the 14th Amendment of the Constitution, Judge Dillon says: "It was of

set purpose that its prohibitions were directed to any and every form and

mode of State action - whether in the shape of constitutions, statutes,

or judicial judgments - that deprived any person, white or black, natural

or corporate, of life, liberty, or property, or of the equal protection

of the laws. Its value consists in the great fundamental principles of

right and justice which it embodies and makes part of the organic law of

the nation." If these rights are to have any meaning, the State cannot

evade its obligations here.

The Court of Appeals affirmed Judge Niles resting its decision on constitutional

grounds. The judge said that "[I]t would be strange indeed, in the fact

of the solemn constitutional guarantee, which places private property among

the fundamental and indestructible rights of the citizens, if [the] principle

of [sovereign immunity] could be extended and applied so as to preclude

him from prosecuting an action of ejectment against a State Official unjustly

and wrongfully withholding property." The judges in essence told the State

to settle the case or condemn the Gibson property. So presumably, they

received a little more than a penny.

Although rarely cited for 80 years, in the 1980s and 1990s Weyler

v. Gibson became the cornerstone of the Court's unique constitutional

torts jurisprudence. As a result of Weyler, State and local officials

have no immunity from a state constitutional claim such as taking of property

or deprivation of due process. It is hard to imagine a greater deterrent

to arbitrary and unconstitutional State conduct.

*****************************

![Thurgood Marshall and Donald Gaines Murray [MSA SC 2221-1-11], d012164a](../images/d012164a.jpg) A

major event in the history of the Court of Appeals also happened to be

a major event in the history of the civil rights movement and a major event

in the life of Thurgood Marshall. It began in 1930 when Marshall was denied

admission to the University of Maryland Law School solely because of his

race. Instead of being allowed to attend a school in his home state that

was a 10-minute trolley ride from his home, Marshall for three years had

a grueling commute to Howard University in Washington, D.C. There he graduated

first in his class. After he passed the Maryland bar, he began a private

practice. Soon however, his major occupation was helping to rebuild the

Baltimore branch of the NAACP and planning litigation to open doors for

African Americans, particularly at post-graduate institutions such as the

University of Maryland Law School.

A

major event in the history of the Court of Appeals also happened to be

a major event in the history of the civil rights movement and a major event

in the life of Thurgood Marshall. It began in 1930 when Marshall was denied

admission to the University of Maryland Law School solely because of his

race. Instead of being allowed to attend a school in his home state that

was a 10-minute trolley ride from his home, Marshall for three years had

a grueling commute to Howard University in Washington, D.C. There he graduated

first in his class. After he passed the Maryland bar, he began a private

practice. Soon however, his major occupation was helping to rebuild the

Baltimore branch of the NAACP and planning litigation to open doors for

African Americans, particularly at post-graduate institutions such as the

University of Maryland Law School.

Marshall helped choose an ideal plaintiff to attack the segregationist

policies of the law school -- Donald Gaines Murray, a 20-year old Amherst

graduate. Murray wrote once to the University and received back a form

letter advising him of the school's separatist policies, but of the possibility

of a scholarship at an out of state school. He applied once, then twice

to Maryland, but was denied admission on both occasions. The last letter

notified Murray of the "exceptional facilities open to you for the study

of law" at Howard University. Soon thereafter Marshall filed a mandamus

action against the University of Maryland, seeking Murray's admission.

Using the "Separate but Equal" doctrine as a sword, Marshall charged that

the University's policies denied equal protection because there was no

state law school for African American students. Even though there had never

been a court-ordered desegregation of a public school, Marshall convinced

Baltimore City Judge Eugene O'Dunne that the

University's exclusionary policy was unconstitutional and that a mandamus

should issue. An appeal followed to the Court of Appeals. Arguing for the

State was Assistant Attorney General Charles LeViness; for Murray, Thurgood

Marshall.

UNIVERSITY V. MURRAY

Charles LeViness for Appellant:

While preserving Maryland's traditional policy of separation of the

races, the State has met the demand of the negroes for higher education

by establishing a system of scholarships to institutions out of the State

for the exclusive use and benefit of colored students. This scholarship

policy was launched by the Legislature of 1933, which provided that the

Board of Regents of the University of Maryland might set apart a portion

of the State appropriation for Princess Anne Academy and establish scholarships

for negro students who might wish to take professional courses or other

work not offered in Princess Anne but which were offered white students

at the University of Maryland.

To its negro citizens who desire to take up law work, Maryland says

substantially this: "under our policy of separate schools for both races

it is permissible and proper for the University of Maryland Law School

to deny your admittance. If you were admitted you would have to pay the

tuition fee of $203 a year. We cannot yet give you a separate law school

in the State: there is no sufficient demand for it, nor sufficient money

available to start it. However, to even things up, we will pay your tuition

at some law school of your own selection out of the State. You will save

the $203 tuition fee at Maryland and you may apply this money to your maintenance

at the law school of your choice."

The classification of students is a matter of internal State policy.

If it were unconstitutional to classify on the basis of race, it also would

be improper to classify on the basis of studies, or on the basis of sex.

Certainly it cannot be contended that if a state provided a law school

for its citizens it also must provide a medical school, or an engineering

school. The University of Maryland includes among its Baltimore Schools

a law school and a medical school. It does not include an engineering school.

And yet this is a discrimination in favor of those desiring to study law

or medicine and against those desiring to study engineering. Similarly

a state might provide, without encountering constitutional objections,

a certain school for men without a corresponding school for women. Distinctions

on the basis of sex uniformly have been upheld by the courts.

In the absence of statute compelling mixture of the races at professional

levels, it is submitted that the Regents are entirely within their rights

in cleaving fast to Maryland's traditional policy of separation.

![Thurgood Marshall [MSA SC 2221-1-11], d012191a](../images/d012191a.jpg) Thurgood

Marshall for Appellee:

Thurgood

Marshall for Appellee:

What is at stake here is more than the rights of my client. It is the

moral commitment stated in our country's creed. The State is under no compulsion

to establish a state university. Yet if a state university is established,

the rights of white and black are measured by the test of equality in privileges

and opportunities. No arbitrary right to exclude qualified students from

the University of Maryland is claimed by appellants except as to qualified

Negroes, whom the administrative authority would reject on the sole ground

of race or color.

While the Board of Regents of the University of Maryland has large and

discretionary powers in regard to the management and control of the University,

it has no power to make class distinctions or practice racial discrimination.

The reason is obvious. A discrimination by the Board of Regents against

Negroes today may well spread to a discrimination against Jews on the morrow;

Catholics on the day following; red headed men the day after that.

The dual and inferior standard which appellants apply to Negro education

is evidenced by the pitiful attempt of the President of the University

on the witness stand to assert that just as good a course was offered at

Princess Anne as at College Park. May it please the Court, a college of

technology

for Negroes does not compare equably with a college of

law for white

students, whatever the cost. It is the essence of the idea of 'equality'

in this case that the facilities be the same. There is no school of

law for Negroes in the State of Maryland. Further it does not sound

well for the agents of the State to complain that there is no great demand

on the part of Negroes for collegiate and professional education, when

the State itself has made it difficult for Maryland Negroes to qualify

for collegiate and professional education because of the inferior elementary

schools which the State and counties maintain and the absence of adequate

high school facilities for Negroes.

The State's scholarship program is a specious gesture to delude the

Negro population of Maryland and keep it quiet. The scholarship is but

a tempting mess of pottage held out to induce my client to sell his citizenship

rights to the same treatment which other citizens of Maryland receive,

no more and no less. Equivalents must also be considered in terms of self-respect.

Appellee is a citizen ready to pay the same rate of taxes as any other

citizen, and to go as far as any other citizen in discharge of the duties

of citizenship to state and nation. He does not want the scholarship or

any other special treatment.

We do not concede that it is constitutional for a State to export its

obligations and to exile one set of its citizens beyond its borders to

obtain the same education which it is offering to citizens of different

color at home. It is not without significance that all the "free scholarships"

which the State provides for its white citizens are in Maryland colleges

and universities. Only its Negro citizens are exiled.

Finally Mr. Murray is an individual. His years and days are numbered,

and he cannot wait for his education until there is a mass demand to the

satisfaction of the Regents. A citizen's constitutional rights receive

protection on an individual basis.

On January 15, 1936 -- Martin Luther King's seventh birthday -- a unanimous

Court of Appeals affirmed, agreeing that Murray had to be admitted to the

University of Maryland Law School. The building of a second school was

not deemed an available alternative remedy. Chief Judge Bond wrote that

"[c]ompliance with the Constitution cannot be deferred at the will of the

State. Whatever system it adopts for legal education now must furnish equality

of treatment now."

![Judge Carroll T. Bond [MSA SC 1545-1150], i002982a](../images/i002982a.jpg)

We all know what happened to Marshall. In Brown v. Board of Education,

he

successfully attacked as unconstitutional the separate but equal doctrine

he relied on in Murray, as the Supreme Court opened the doors of

segregated public schools throughout the country. Then, as Solicitor General

and later as Justice of the Supreme Court, Marshall continued his lifelong

dedication to the preservation of civil rights. One biographer of Marshall

has said that he was actually hoping for a loss in Murray, so that

the issue might be taken to the Supreme Court for a ruling of greater impact.

However, upon his retirement from the Court in 1991, Marshall admitted

that his 1936 victory was "sweet revenge".

![Donald Gaines Murray statue [MSA SC 1545-2944], i002959a](../images/i002959a.jpg)

![Donald Gaines Murray statue [MSA SC 1545-2944], i002960a](../images/i002960a.jpg)

After losing to Marshall, Assistant Attorney LeViness was quoted as

saying " he hoped that Murray would finish first in his class at the University

of Maryland Law School." Like his classmates, Louis Goldstein and Fred

Malkus, Murray did not finish first in his class. But he graduated, became

a respected member of the bar, practiced in Baltimore, and continued to

devote his energies to NAACP civil rights work. His statue can be found

in Lawyer's Mall in Annapolis, not far from that of Marshall's, on the

very spot where the Court of Appeals building once stood.

*****************************

It is 28 years later and once again much has changed both with respect

to the Court of Appeals and the judicial system. A 1944 constitutional

amendment reduced the size of the court to its present level of seven judges,

but more importantly confirmed the Court's key executive and legislative

roles in the administration of the state judicial system. By the 1960s

the Supreme Court's criminal justice revolution foreshadowed the need for

an intermediate appellate court to handle the suddenly heavy workload of

criminal cases. However, Maryland was to create its own mini-criminal justice

revolution stemming from a routine murder case tried in the Circuit

Court for Cecil County in the late summer of 1964.

![Schowgurow arrest, Cecil Democrat, 1/8/1964, [MSA SC 221-1-24], i003058b](../images/i003058b.jpg)

Lidge Schowgurow, a Buddhist who disavowed

a belief in God, was accused of murdering his wife. He was indicted by

a grand jury and convicted by a petit jury required by Article 36 of the

Maryland Declaration of Rights to believe in the existence of God. Challenging

his conviction of first degree murder as a violation of the First and Fourteenth

Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, Schowgurow appealed to the Court of

Appeals. He was represented by J. Grahame Walker; the State, by Assistant

Attorney General Roger D. Redden.

*****************************

SCHOWGUROW V. STATE

J. Grahame Walker for Appellant:

Mr. Schowgurow was raised in the Buddhist faith. In an affidavit duly

filed he stated that the Buddhist religion to which he adheres does not

teach a belief in the existence of God or a Supreme Being. He challenged

the compositions of the grand jury which indicted him and the petit jury

which tried and convicted him because Article 36 of the Declaration of

Rights requires jurors to express a belief in God and that requirement

deprives him of due process and equal protection of the law.

Four years ago in Torcaso v. Watkins, the Supreme Court told

the State of Maryland that it's requirement that public officers believe

in God invaded their freedom of religion. What is unconstitutional for

an officer is no less offensive for jurors.

The jurors in this case were sworn in accordance with the requirements

of Article 36 and obliged to profess their belief in God. It is common

knowledge that substantial minorities do not profess to believe in God

and it is presumed that such persons exist among the citizens of Maryland

and the residents of Cecil County.

We don't need to know how many Buddhists live in Cecil County or whether

they were deliberately excluded from the grand and petit juries. No proof

of discrimination is needed where the State Constitution requires the exercise

of discrimination. Article 36, by its very terms, sets apart and discriminates

against a segment of citizens who do not believe in the existence of God.

It clearly prohibits an accused, whether a believer or a non-believer,

from being tried by a jury composed of persons who do not believe in God,

as well as persons professing a belief in God. Its application can easily

result in prejudice to an accused when his lack of belief is manifested

to the jury by his failure to take the oath before testifying.

The First Amendment proscribes the use of essentially religious means

to serve governmental ends. The trial, conviction and punishment of an

offender is solely a government function for the protection of society.

Its secular character is obvious, but is perhaps best illustrated by the

imposition of a death sentence, which would be hard to justify under any

known religion. If the doctrine of separation of church and state is to

mean anything, this Court should find that Article 36 has violated Appellant's

constitutional rights and his conviction must be set aside.

Assistant Attorney General Roger D. Redden for Appellant:

Due process of law is an oracular concept which eludes expository definition.

Even the prodigious intellect of Justice Frankfurter found the task staggering.

But, however complex the problem of definition, one finds solace, and at

least visceral comprehension, in resort to due process's equivalent and

basic measure -- fairness.

The question before this Court is one of fairness alone, and in that

portion of the criminal process which is devoted to the selection of jurymen,

fairness requires only that the jury be indiscriminately drawn from among

those eligible in the community for jury service, untrammeled by any arbitrary

and systematic exclusions.

The Appellant, a Buddhist, asserts that his co-religionists have been

a priori excluded from Cecil County jury service because (1) they

do not believe in the existence of God and (2) nonbelievers are excluded

from Cecil County jury service on account of Article 36 of the Maryland

Declaration of Rights.

Here is the center of dispute. Mr. Schowgurow has proved nothing beyond

his own allegiance to the Buddhist faith. He has not even tried to prove

anything else. There is nothing in the record to show that there has ever

been a single adherent of Buddhism resident in Cecil County who, aside

from the belief-in-God issue, was otherwise qualified to serve as a juror,

let alone that any Buddhist was excluded from the call or, being called,

was excluded from the panel for failure to affirm his belief in the existence

in God.

The only pertinent evidence of any kind is the uniform declaration

of the oaths administered by the Clerk of the Circuit Court for Cecil County:

"In the presence of Almighty God, you ... do solemnly promise and declare

that ...". This declaration is no filter through which nonbelievers cannot

pass. Appellant negotiated it himself without difficulty when he testified

during his trial, a fact which exposes the desperate emptiness of his present

claim, something conjured up from a series of unfounded assumptions.

As to the Torcaso decision, it helps not hurts the State's position.

First, to the extent that Maryland caselaw may be construed to opine that

the discovery of a single nonbeliever on a panel voids that panel's action,

it was overruled by Torcaso, which held that expression of a belief

in the existence of God could not be imposed as a condition precedent to

holding public office.

Second, Mr. Justice Black's identification of Buddhism as an atheist

religion in Torcaso does nothing but confirm what the encyclopedists

tell us. It does not create any presumption as to the extent of Buddhist

practice in Maryland. It does not plant nor evangelize Buddhism on the

Eastern Shore. It does not oblige the State's Attorney for Cecil County

to canvass the countryside for naysaying witnesses to prove what is a good

deal closer to common knowledge than the tenets of Buddhism - that resident

adherents to Buddhism are unknown to Cecil County.

The Appellant has not met minimal standards of showing unfairness and

his conviction should be affirmed.

*****************************

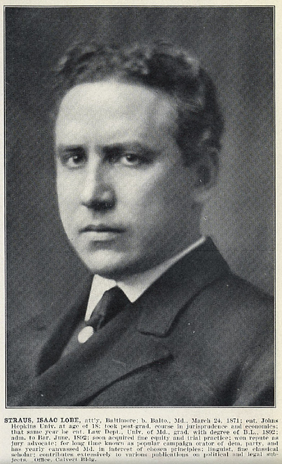

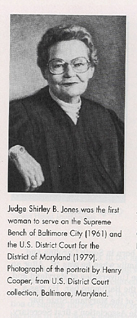

The

Schowgurow

case was reargued and the panel included specially assigned Circuit Court

Judge Shirley Jones, the first woman to sit on the Court of Appeals (however

briefly). The Court, in October 1965, announced its anguished but almost

inevitable decision that the belief in God requirement for grand and petit

jurors was unconstitutional. Rejecting the State's and a dissent's contention

that no prejudice had been shown, the majority held that an actual showing

of discrimination was not necessary when the exclusion of nonbelievers

was "not only authorized but demanded by the Maryland Constitution." In

a seeming victory for the State, the Court held that its decision did not

apply retroactively "except for convictions which have not become final."

But later decisions made it clear that a defendant could not implicitly

waive this issue if his or her conviction was not final before

Schowgurow.

According to the Attorney General, this meant that two or three thousand

defendants had to be reindicted.

The

Schowgurow

case was reargued and the panel included specially assigned Circuit Court

Judge Shirley Jones, the first woman to sit on the Court of Appeals (however

briefly). The Court, in October 1965, announced its anguished but almost

inevitable decision that the belief in God requirement for grand and petit

jurors was unconstitutional. Rejecting the State's and a dissent's contention

that no prejudice had been shown, the majority held that an actual showing

of discrimination was not necessary when the exclusion of nonbelievers

was "not only authorized but demanded by the Maryland Constitution." In

a seeming victory for the State, the Court held that its decision did not

apply retroactively "except for convictions which have not become final."

But later decisions made it clear that a defendant could not implicitly

waive this issue if his or her conviction was not final before

Schowgurow.

According to the Attorney General, this meant that two or three thousand

defendants had to be reindicted.

Not only did Schowgurow move the criminal justice system into

overdrive, but when some defendants on retrial received a higher sentence,

double jeopardy claims were pressed. These Maryland cases eventually reached

the Supreme Court and convinced the justices for the first time to apply

the Double Jeopardy Clause of the Fifth Amendment to the States. As to

Lidge Schowgurow, after his retrial resulted in a hung jury and a mistrial,

he pled guilty in exchange for an 18-year sentence.

*****************************

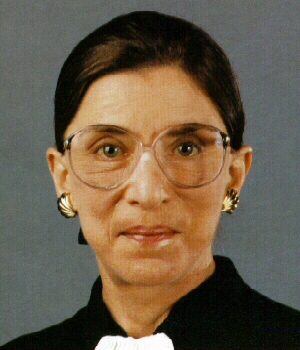

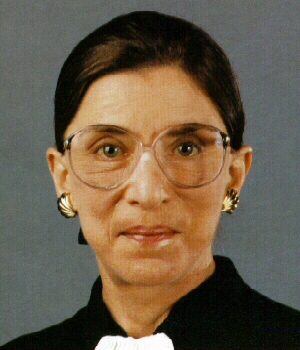

Our last argument occurred some 27 hears ago and, although the Court

appeared to change very little since 1965, the world had changed immeasurably.

The typical woman was no longer a June Cleaver. She had entered the workforce,

the marketplace, the practice of law. She was no longer imprisoned by stereotypes

or quietly willing to accept discrimination. Mary Emily Stuart was such

a woman.

Married to Samuel Austell, Ms. Stuart continued after her marriage to

use her birth name. But when she tried to register to vote with the local

Election Board, she was told that under state law she had to register as

Mrs. Austell. Stuart promptly filed suit in the Circuit

Court for Howard County, raising both statutory and constitutional

claims to the apparent state bar to the use of her real name. Denied relief,

she appealed to the Court of Appeals and was joined by a number of Friends

of the Court, including the ACLU represented by Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Stuart

was represented by Arold Ripperger; the State Election Board by E. Stephen

Derby.

*****************************

STUART V. BOARD OF SUPERVISORS

Arold Ripperger for Appellant:

Mary Emily Stuart testified below that her marriage to Samuel Austell

was "based on the idea that we're both equal individuals and our names

symbolize that." Indeed, she said she would not have gotten married if

it would have jeopardized her name. Her name is on charge accounts, her

driver's license and social security registration. Everyone, she testified,

knows her by the name Mary Stuart.

Neither Maryland common law nor its election laws force her to deny

the truth and register to vote in her husband's name. The common law rule

is that a person may adopt any name he or she wishes in the absence of

fraud or deceit.

As it was at common law, so now is it the option of a married woman

to choose the name that she desires to use. Nellie Marie Marshall retained

the name of her first husband at the time of her second marriage. Amy Vanderbilt,

who has been married four times, said, "I have always used my maiden name."

Lynn Fontanne, of the fabled Lunt and Fontanne acting team, adopted a hyphenated

name, Fontanne-Lunt, as her legal name. Lucy Stone looked upon the loss

of a woman's name at marriage as a symbol of a loss of her individuality

and consulted several eminent lawyers, including Salmon P. Chase, later

Chief Justice of the United States, and was assured that there was no law

requiring the wife to take her husband's name, only a custom. She remained

Lucy Stone.

It is true that §3-18 of the Election Code requires clerks of court

to notify election boards of the "present names" of women over the age

of 18 after being advised of a "change of name by marriage." However, that

statute does not apply in this case. Mary Stuart did not change her name

by marriage. There was no duty to advise the clerk, no duty on the part

of the clerk to advise the election board and no duty or authority of the

election board to question the name under which Mary Stuart sought to register

to vote.

If Maryland's law required a false registration by Mary Stuart, it would

be unconstitutional. As the Amicus ACLU has argued, sex like race and alienage

is an immutable trait, a status into which class members are locked by

the accident of birth. The requirement that a married woman assume her

husband's name to register to vote is not reasonable, but places her in

equal status with infants, lunatics and convicted felons. By whatever name

the Board of Elections calls its practice - administrative convenience,

necessary procedure, mandatory requirement, it is discrimination and discrimination

based solely on sex. In its simplest terms, a married woman is denied the

statutory right to contract with her husband or she is denied her constitutional

right to vote.

Assistant

Attorney General E. Stephen Derby for Appellees:

Assistant

Attorney General E. Stephen Derby for Appellees:

Today it is almost a universal rule in this country that upon marriage,

as a matter of law, a wife's surname becomes that of her husband. While

a wife may continue to use her maiden name for professional and other purposes,

her name as a matter of public record is that of her husband.

The provisions of §3-18 on their face are premised upon an assumption

by the Legislature that a woman's name does change when she marries, in

accordance with the common law rule. Any other conclusion would deprive

the provisions of meaning because the only information possessed by the

clerk of court is the fact of the marriage. The administrative application

of the statute to require every woman voter who has married to change her

name on the registration books gives the section meaning. If a married

woman could elect whether to adopt her married name for voting, then the

purpose of the statute in furthering the State's interests in preventing

voter fraud, in providing an accurate trail of identification, and in uniform

record keeping would not be served.

The State Elections Administrator testified that there are approximately

1,762,000 registered voters in Maryland. Assuming one half are female and

the majority of them are or will be at some time married, it will be necessary

to have a trail to identify persons and to prevent voter fraud. If a married

woman could register under different names, the identification trail would

be lost. As a practical matter the election boards of the State are not

in a position to make complicated factual determinations as to whether

a married woman voter is not and has never been known by her married surname.

Therefore, it is reasonable for the boards, to insist always upon use of

the surname adopted by marriage unless a married woman has taken the relatively

easy step of changing her name legally for all purposes by a court order.

There is simply no constitutional issue in this case involving a denial

of the right to vote because appellant has not been denied that right.

It is completely within her power and discretion to register to vote. She

is required to do so in her legal name, whether by common law or custom,

but no burden is imposed upon her which impinges upon her right to vote.

To the extent that the Court may find that a discrimination does exist,

it is one based on sex and marriage because of the automatic consequent

that, absent a legal change of name, a woman's surname becomes that of

her husband upon marriage. If it exists, the discrimination is one caused

by the uniform common law rule or custom, applicable to married women,

and it is not one involving the elective franchise. The right involved

is the right to assume any name a person wishes. However, the right to

assume a name of one's choice does not have constitutional status. Rather

it is based on common law. Furthermore, the Supreme Court has yet to hold

that discriminations based on sex are inherently suspect.

Whatever inconvenience the State rule may cause Appellant is slight

when weighed against the interests of the State in uniform recordkeeping,

in accurate identification of voters, and in preventing voter fraud.

*****************************

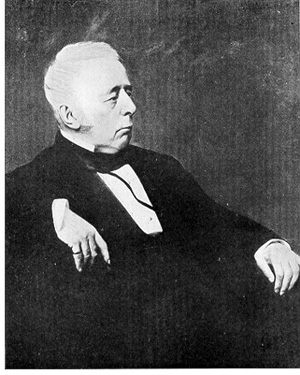

![Chief Judge Robert C. Murphy [MSA SC 1198], i003000a](../images/i003000a.jpg)

A month before state voters approved an Equal Rights Amendment, on October

9, 1972, in his first opinion of his 24-year career on the Court, Chief

Judge Robert C. Murphy, concluded that Maryland common law permits a Maryland

woman to retain her birth name and to use it nonfraudulently after her

marriage. The majority over one dissent also found that state election

laws did not forbid such use because Stuart did not undergo a "change in

name by marriage".

![Robert C. Murphy Court of Appeals Building [MSA SC 1885-758-2], i001827b](../images/i001827b.jpg)

The very next day, the judges dedicated a new courthouse on Rowe Boulevard

-- the Court's present location. At the same time, the Court adopted distinctive

new judicial garb -- actually a return to the dress worn by members immediately

after the Revolutionary War: scarlet rather than black robes and a stock

with tabs. More than location and robes would change, as within a few short

years, the Court would have its first woman and African-American members.

Now more than 223 years old, the Court of Appeals remains a progressive

and respected institution, with much of its glorious history remaining

to unfold.

Return

to A Court of Appeals Time Capsule introduction

Return

to Six Significant Maryland Appellate Cases document packet

![Interior of Court of Appeals, ca. 1860s [MSA SC 182-90], i002957a](../images/i002957a.jpg) Journey

back to the early part of the 19th Century -- 1821 to be exact. The Court

is presently composed of six appointed judges who were also trial judges.

It has been located in a room in the State House

for some 40 years, although the Court also sits on the Eastern Shore. We

believe the judges wore robes, but they probably did not have an elevated

bench. The room looks very much like a trial courtroom. There was no limit

on the length of oral argument. It would not be until 1826, that the Court

would fix a six-hour limit on arguments on the Western Shore. Arguments

by members -- of what was probably a genuine appellate bar--could run for

days and were marked by dramatic performance, flights of eloquence, learned

allusions and, given their length, a great deal of tedium.

Journey

back to the early part of the 19th Century -- 1821 to be exact. The Court

is presently composed of six appointed judges who were also trial judges.

It has been located in a room in the State House

for some 40 years, although the Court also sits on the Eastern Shore. We

believe the judges wore robes, but they probably did not have an elevated

bench. The room looks very much like a trial courtroom. There was no limit

on the length of oral argument. It would not be until 1826, that the Court

would fix a six-hour limit on arguments on the Western Shore. Arguments

by members -- of what was probably a genuine appellate bar--could run for

days and were marked by dramatic performance, flights of eloquence, learned

allusions and, given their length, a great deal of tedium.

![Luther Martin, Rosenthal Engravings [MSA SC 2221-1-24], i003005a](../images/i003005a.jpg)

![Judge John Buchanan [MSA SC 1545-1155], i002983a](../images/i002983a.jpg)

![Court of Appeals building, ca. 1903 [MSA SC 1754-2-124], i002977a](../images/i002977a.jpg)

![Thurgood Marshall and Donald Gaines Murray [MSA SC 2221-1-11], d012164a](../images/d012164a.jpg)

![Thurgood Marshall [MSA SC 2221-1-11], d012191a](../images/d012191a.jpg)

![Judge Carroll T. Bond [MSA SC 1545-1150], i002982a](../images/i002982a.jpg)

![Donald Gaines Murray statue [MSA SC 1545-2944], i002959a](../images/i002959a.jpg)

![Donald Gaines Murray statue [MSA SC 1545-2944], i002960a](../images/i002960a.jpg)

![Schowgurow arrest, Cecil Democrat, 1/8/1964, [MSA SC 221-1-24], i003058b](../images/i003058b.jpg)

Assistant

Attorney General E. Stephen Derby for Appellees:

Assistant

Attorney General E. Stephen Derby for Appellees:![Chief Judge Robert C. Murphy [MSA SC 1198], i003000a](../images/i003000a.jpg)

![Robert C. Murphy Court of Appeals Building [MSA SC 1885-758-2], i001827b](../images/i001827b.jpg)