The War of 1812 in Maryland

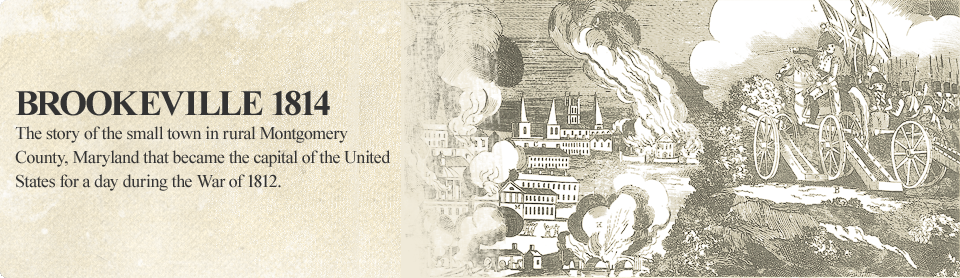

"Sketch of the action fought near Bladensberg, August 24th, 1814." Thos. Ormsby, 1816.

Library of Congress. (Click to enlarge).In June of 1812, the United States went to war.

The hostilities came after years of simmering tensions with Great Britain, at a time when a young America wanted to assert its strength. To prove the country's place in the world, and end degrading British harassment, the United States declared war, sent out a swarm of privateers, and invaded Canada.

In doing so, the country thrust itself into a conflict for which it was barely prepared. In many ways- excluding the battles of Baltimore and New Orleans at the end of the war- the war was a disaster.

The United States achieved a handful of famous naval victories, but still lost control of the waters off its coast. The invasion of Canada did not produce the expected uprising against the colony's British rulers. Instead, the British and Canadians soundly defeated the Americans.

"The enemy nearly all 'round us"

To Marylanders, the war came in February 1813, when the British sailed into the Chesapeake Bay and began a campaign to terrorize the coast. With orders to "Destroy & lay waste [to] such Towns and Districts... as you may find assailable," their goal was to take advantage of the Bay's long, unguarded coastline, and to demoralize the population. This, the British hoped, would push the Americans to end the war, without requiring Britain to use troops more urgently needed in its campaign against Napoleon.

The British attacked towns large and small along the Bay throughout 1813 and 1814, looting farms, burning houses, taking food and supplies, and destroying crops. As one resident noted in his diary, "The enemy [is] nearly all 'round us & up and down the Patuxent & in the Bay."

The British also offered freedom to all of the area's slaves, and hundreds escaped to British ships and encampments. The slaves found freedom and sanctuary, as well as opportunities for revenge against those who had enslaved them. Some freed slaves enlisted to fight with the British, while others served as scouts. One American complained that the slaves "leave us as spies upon our posts and our strength, and return upon us as guides and soldiers and incendiaries."

The Burning of Washington

In the summer of 1814, the British campaign in the Chesapeake reached a new intensity. Eager to end the war, and with troops newly available after the defeat of Napoleon, the British set their sights on Washington. The city was lightly defended, and on August 24, the British swept aside the city's defenders at Bladensburg, a battle derisively dubbed the "Bladensburgh Races," after a nearby horse race. That evening, British soldiers and marines stormed into the American capital. They burned the White House, the Capitol building, and most of the city's public buildings.

Nearly all private homes and businesses were spared by the British and only a few houses were destroyed, along with the office of the stridently pro-war National Intelligencer newspaper. Still, in the days before the attack, many residents of the area fled ahead of the British advance, seeking refuge in the surrounding countryside, or even as far away as Frederick. Some journeyed twenty miles north to the small town of Brookeville, where they were joined by President James Madison two days after the burning of Washington.

The President's stay in Brookeville was brief, and the war itself was to be resolved soon. The British next turned northward up the Chesapeake Bay, headed for an even bigger prize: Baltimore. However, their ground assault was turned back at the Battle of North Point, their leader General Robert Ross was killed, and their ships were unable to overcome Fort McHenry and the harbor's defenses. In January, 1815, the British were again defeated, at New Orleans, and a few weeks later news arrived from Europe that a peace treaty had been signed. The war was over.