|

210 East Lexington:The Douglass Institute |

|

210 East Lexington:The Douglass Institute |

On May 19th, 1870, Frederick Douglass spoke to a crowd assembled to witness the largest African American parade in U.S. history prior to the 1950's. The crowd was celebrating the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment. According to reports in the Sun and the News American, Douglass spoke movingly of his past as a slave and of the promise of freedom. Douglass told his listeners of the need for African Americans to work hard, earn money, and get an education for their children. Most importantly, he urged them to exercise their newly won right to vote.

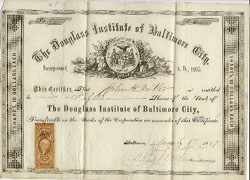

When the parade ended, Douglass and other dignitaries attended a dinner at 11 East Lexington Street (the old number for the current 210). Five years before, he had gone to that same address to dedicate an institution that would become the focal point of the city's African American community between 1865 and 1890: the Douglass Institute, named in his honor. The original founders were white because blacks were not permitted to incorporate. The board of directors changed when the Institute took out a new charter in 1872, after African Americans could legally form corporations.

The Douglass Institute hosted countless meetings of organizations promoting

African American causes. Post 7 of the Grand Army of the Republic and the

Order of Odd Fellows used the hall, as did black leaders of the Republican

Party.  These

leaders met in the Institute and organized efforts to open schools for

blacks, to have black teachers hired by the city, and to meet the black

community's other needs. By 1889, the Douglass Institute had performed

its duties so well that its members decided to liquidate its holdings and

disband. At President Butler's encouragement, the stockholders sued to

have the courts properly dispense with the Institute's property, which

included 11 East Lexington and several rental properties.

These

leaders met in the Institute and organized efforts to open schools for

blacks, to have black teachers hired by the city, and to meet the black

community's other needs. By 1889, the Douglass Institute had performed

its duties so well that its members decided to liquidate its holdings and

disband. At President Butler's encouragement, the stockholders sued to

have the courts properly dispense with the Institute's property, which

included 11 East Lexington and several rental properties.

Much of the story of the Douglass Institute is contained in equity papers from the Circuit Court of Baltimore which are in the collections of the State Archives. Land records there show that the building was auctioned off by the trustees and purchased by the Abell family, the owners of the Baltimore Sun. The new owners constructed an office building on the foundations of the old Institute. Did the vigorously Democratic family intentionally destroy a Republican and African American landmark and replace it with a building named after a famous Democratic city mayor?

![]() The

Fascinating History of 210 E. Lexington

The

Fascinating History of 210 E. Lexington

![]() Return

to "Civil Rights & Politics" Introduction

Return

to "Civil Rights & Politics" Introduction

![]() Return

to The Road From Frederick To Thurgood Introduction

Return

to The Road From Frederick To Thurgood Introduction

Copyright: Maryland State Archives, 1997