Carroll County

Maryland State Archives Phone: (410) 260-6400 350 Rowe Boulevard http://mdsa.net/msa/speccol/sc2200/sc2221/000031/html/0000.html Annapolis, MD 21401 archives@mdarchives.state.md.us

|

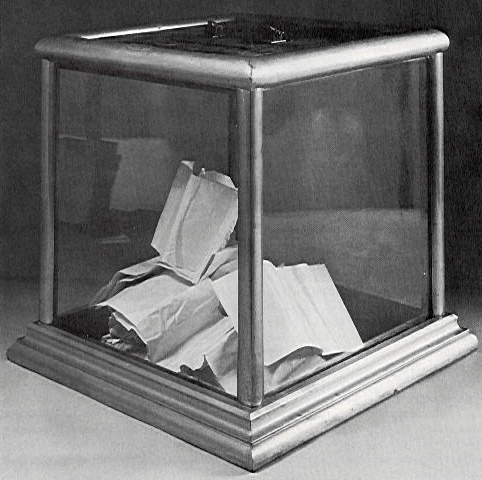

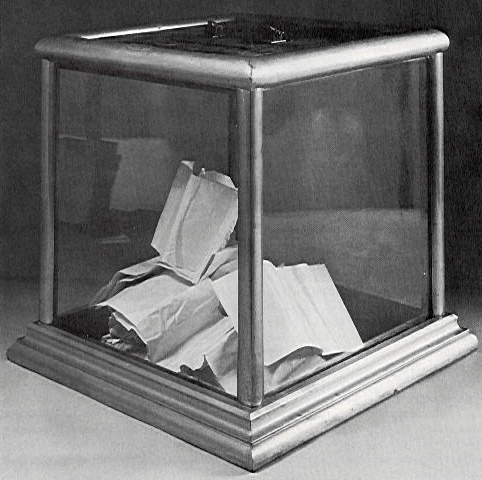

| Ballot Box, c. 1900. Historical Society

of

Carroll County |

As a service to the school children and teachers of Maryland and to scholars everywhere, the Maryland State Archives is pleased to provide a new addition to its on-line Archives of Maryland on the history and significance of Maryland's Electoral College. Some see the institution as an anachronism. Others argue that it is one of the more venerable and successful of all the innovations in government created by the Constitutional Convention of 1787. While it is not our role to take sides, it is to provide as much of its history as accurately and completely as possible, drawing on the official records of government, biographical sketches of the participants, and such fragile sources of our past as newspaper accounts, which if not preserved and made accessible through the medium of electronic imagery and microfilm, will not be there to help us make informed judgments about public policy.

History helps us to understand that the problems we face each generation are a combination of the new and the familiar. That much of what we struggle with to make our lives better and more fulfilling, our predecessors confronted with varying degrees of success. Take for example the matter of electing a president of the United States. Two hundred and fourteen years ago this summer in Philadelphia, a room full of men meeting in secret thought they knew what was best for our future and gave us the electoral college. Just how wise were they and what can we learn from the consequences of their actions?

At approximately 2:04 p.m. Eastern Standard Time on January 6, 2001, Maryland's ten electoral votes for President of the United States were officially accepted and recorded in a Joint Session of Congress presided over by the Vice President of the United States who happened also to be a defeated candidate for the Nation's highest office. In a slow and deliberate ceremony carried live over CSPAN and a handful of other channels, less than a quorum of the members of the House of Representatives, and the Senate of the United States were watched by a small national audience as they performed duties prescribed under the Constitution of the United States designed to bring closure to what was one of the closest elections in American History. The following day, while the New York Times carried a front page photograph of the proceedings, the Baltimore Sun failed to mention them at all.

There had been close presidential elections before. In 1888, Benjamin Harrison, the winner of the electoral vote, and thus the presidency, failed to carry the popular vote. In 1876 Congress, for the first and last time, entrusted the final count to an Electoral Commission that became embroiled in controversy when it awarded the electoral vote to the loser of the popular vote, Rutherford B. Hayes. In 1824, supporters of Andrew Jackson claimed he had won the popular vote, but because six of the then twenty-four states still chose their Electors in the State Legislature, we will never know for certain. By far the most influential of all close elections, however, was that of 1800 when Maryland's and the Nation's electoral vote was evenly divided between Aaron Burr and Thomas Jefferson. Only after 36 ballots in the House of Representatives was Jefferson elected President. To prevent a similar occurrence from ever happening again, the 12th Amendment to the Constitution was adopted whereby electoral votes were to be cast separately for President and Vice President, and electors could not vote for more than one candidate from their home state. More importantly, however, the Election of 1800 marked the beginning of a trend towards direct election of presidential electors by the people and a gradual shift (most notable first in the election of 1824) in favor of the winner of the popular vote in each state determining the allocation of the electoral vote. I say gradual, because Maryland did not require its electors to vote for the winner of the popular vote until 1957.

One of the closest elections in Maryland history, and,

as John Willis points out in Presidential Elections in Maryland

(1986), the "closest of any contest between the Democratic and Republican

parties in any state in the history of American presidential elections,"

was the Presidential election of 1904. In matters of procedure, the

presidential election of 1904 was a watershed in the Maryland political

process. It was the first presidential election in which a secret

paper ballot, supplied at public expense, and without political symbols

of any kind, was issued to each voter. Candidates for Electors were

listed under the presidential and vice presidential candidates for each

party (there were four parties recognized in the election, Democratic,

Republican, Prohibition, and Socialist). Voters were free to mark

their ballots for up to eight candidates of any party. Partisan newspapers

in the weeks before the election carried explicit instructions such as

those issued by the Democratic Central Committee and published on the front

page of the Annapolis

Capital on November 1, 1904, a week before

the election. While chads were not a problem, how you marked your ballot

was.

How to Vote the TicketThis method of balloting was a far cry from the methods of the not too distant past. Secret ballots had only been in use in Maryland since 1890 and then for not all the counties until 1892. Prior to that time the parties printed their own ballots for the use of voters, once voice voting was abolished in 1802. Peter Argersinger provides two examples of the coercion, corruption, and chaos that ensued before adoption of the secret or Australian ballot:

...

See that the ballot given you has endorsed upon it the initials of the judge from whom you received it.See that the judge who gives you the ballot calls out your name and residence in a distinct voice.

Vote the ticket by marking a cross (X) mark in the space provided therefore to the right of and opposite the names of Parker and Davis [the Democratic candidates], and also in the space to the right of, and opposite the name of the Democratic candidate for Congress. These two marks will cause your ballot to be counted for the entire Democratic ticket.

The Court of Appeals has decided that the cross mark must be made entirely within the square and not extend beyond it in any way. Any mark whatever on the ballot except the cross (X) mark, whether in the square or out of it, will cause the ballot to be rejected.

If you make a mistake in marking it , do not attempt to make a correction; return it to the judge and get another. You are entitled to a third ballot if the first two have been spoiled and returned, but you must not consume more than seven minutes in marking it. Mark your ballot with indelible pencil which you will find in the election booth.

Do not use your own pencil --- your ballot will not be counted if you do. After marking your ballot, fold it exactly as it was folded when handed to you by the judge, and give it to the ballot judge without permitting anyone to see how you have marked it. See that the judge tears off the coupon and deposits the ballot in the ballot box before you leave the room.

The unregulated private preparation of tickets... produced the famous "pudding tickets." These were tickets much shorter and narrower than usual and printed on tissue paper, which were folded inside a regular ticket to permit multiple voting. The skilled voter could even crimp his ticket with accordion folds, as a fan, with a pudding ticket concealed in each fold; the skilled election judge, in depositing the ticket in ballot box, could fan it out and cause the different pudding tickets to fall out and mix with other tickets already cast. In Baltimore's 1875 election, these tissue pudding tickets account for the discrepancy in one precinct between the 542 votes recorded on the poll list and the 819 ballots counted out of the box....

One observer noted the interaction of party tickets, hawkers, vote-buying, and election day violence in describing the typical election day scenes in Washington County [as reported in the Hagerstown Mail in 1889]:

What we see in Hagerstown is a ward worker off at some distance negotiating with a rounder. A group of men, or maybe one or two standing off and refusing to vote until they have been 'seen'. Then comes a politician to the window holding a floater by the arm and making him vote the ticket he has just given him. Or it may be that a politician on the other side claims this particular floater and grabs him by the other arm and thrusts a different ticket into his hands and then a struggle ensues, in which frequently the whole crowd becomes involved, and it becomes a question of physical strength which party shall receive this free and enlightened vote.

While it was clear within a day of the 1904 election

that Teddy Roosevelt and his running mate Charles Fairbanks were the winners

nationally, the election remained in doubt in Maryland for several days

and was not officially resolved until the meeting of the board of canvassers

in Annapolis on November 30, 1904. On November 12, the Baltimore

American carried the headline "State Hanging in the Balance.

It is a Neck and Neck Race in Maryland," and proceeded to announce that

it appeared that the electoral vote would be evenly divided between the

Democratic and Republican candidates. Voters had some difficulty

with the new ballots. From Cumberland came the report that in Allegany

County the vote for Congress fell behind the presidential vote by 400 votes

in each party "due to the voter failing to find the name of the congressman

on the ballot after he had marked the place for President." Charles

County failed to lock one or more of its ballot boxes and charges of fraud

began to surface, although by November 17, the Baltimore Sun could

report "Charles County Quiet. Election Tangle Straightened Out Satisfactorily."

In the end, the election remained too close to call until the final tally on November 30 when the Board of Canvassers carefully penned a summary of the votes as the official record. By their count, although Theodore Roosevelt and Charles Fairbanks carried the popular vote of the state by a mere 51 votes, only one Republican elector, the well known reformer and advocate of Civil Service reform, Charles Joseph Bonaparte, survived the tally, The remaining seven top vote getters were Democrats, among whom were two well-known and popular former governors, Frank Brown and Elihu E. Jackson. John Willis attributes the split in electoral vote to the name recognition advantage of the Democratic electors, to better party organization and discipline by the Democrats, and to the Democratic state legislature's efforts to confuse the ballot by removing party symbols that proved so helpful to illiterate voters. Not until 1937 would the names of the electors be removed from the Maryland ballot, leaving the voter to choose only among the candidates for President and Vice President.

When the electors met in the Old Senate Chamber of the State House on January 5, 1905 to cast their votes, the Annapolis Capital dwelt perfunctorily on the formalities of the occasion, noting that the "noon hour was spent at the Governor's Mansion, where the members of the electoral college inspected a very interesting portion of the residence. In the afternoon the members again met in session. They signed the three vouchers necessary, drew the $50 each allowed for their work and the event was at an end."

The Baltimore Evening Herald was more philosophical.

In an unsigned front page article that has all the characteristics and

style of a young editor on the paper by the name of H. L. Mencken, the

Evening

Herald reflected on the intent of the founding fathers in creating

an electoral college, and mused about how the electors were originally

intended to act:

There are more than eighty millions of people in this country, and it is safe to say that much more than 99 percent of them do not know that the election takes place today, or if they knew it, suppose that the electors must simply record the wishes of those who elected them in November. The electors need do nothing of the kind, and it was not intended that they should.Mencken failed to note that the very idea of an Electoral College derived in part from the Maryland experience in creating a State Senate under its first Constitution of 1776, a Senate that was indirectly chosen by electors selected by the voters of each county. In two issues of the Federalist, nos. 39 and 63, published in January and March of 1788, James Madison would point with praise to the model of the Maryland Senate, arguing thatIndeed, so far as the intent and purpose of the law are concerned, they should absolutely ignore any recommendation which the people gave last November, and in solemn conclaves should sit as a sort of series of grand juries on the state and nation and select the two best eligible men in the country to act as President and vice-President. The intention of the fathers and of the Constitution is that they shall absolutely use their own judgment and ignore the public clamor.

...

Curiously enough, the manner of electing a President and vice-President , although it looks very large just now, was one of the things to which the constitutional convention gave very little attention. For a long time it seemed as if there would be no constitution at all, so such a detail was not considered. Then when it became evident that there was a chance of an agreement many plans were put forth.

At first it was intended that Congress should choose these magistrates, but it was justly interposed that this would destroy executive independence of the legislative and executive branches of government, which was aimed at, and this was dropped. Some of the delegates wanted to have the oldest Governor in service take the Presidency; others considered that the Governors of various states should serve in turn, and one proposition was seriously considered of putting the names of all the Governors in a hat, from which a blindfolded boy should draw two-- one to be President and the other to be Vice President.

In fact, the convention was getting near adjournment, when the matter had to be settled. As the fathers would in nowise permit the people to choose such distinguished officers, they appointed a selected committee to get up a plan, and the present one (later slightly modified by constitutional amendment) was adopted almost without debate or dissent.

The committee sat in darkness some time before they saw a great light. They would not let Congress do the selecting, and could not trust the people, but they wanted the states to have something to say in the matter. The invention of this new plan was considered a master stroke, and in all the debates over ratification of the constitution by the necessary nine states, which for a long time seemed doubtful, hardly a voice was raised against this provision. Only the wise could elect a President.

....

we may define a republic to be, or at least may bestow that name on, a government which derives all its powers directly or indirectly from the great body of the people, and is administered by persons holding their offices during pleasure, for a limited period, or during good behavior. ... It is SUFFICIENT for such a government that the persons administering it be appointed, either directly or indirectly, by the people; and that they hold their appointments by either of the tenures just specified; otherwise every government in the United States, as well as every other popular government that has been or can be well organized or well executed, would be degraded from the republican character.While the indirect election of Maryland State Senators would end in 1837, not until 1957 would the Maryland Presidential elector's right to act independently be withdrawn. Over the past two hundred and fourteen years we have come to the conclusion that we can put more trust in the direct vote of the people than our founding fathers thought wise.....

In all, the value of history lies in the perspective it provides on the pressing problems of the moment. From it, for example, we learn that not all experiments in government undertaken over two hundred years ago are sacred, nor that they are necessarily as in need of change as they may first appear to be. We have survived and coped well with elections too close to call in the past without abolishing an institution whose original mission seems far less relevant than it once did. What we can say with certainty, however, is that regardless of what we as a nation decide is the future of the Electoral College, the story of our journey with it, teaches us that one of our most precious and zealously fought for rights, is the right to vote. This is a right, which, in the words of Speaker Taylor, is up to you to ensure is "encouraged, protected, and made secure through a system of voting that is as accessible, incorruptible, and accurate as it can possibly be."

note: the Guide to Documents contains all references used in the preparation of this introduction.

Return to Overview

The Archives of Maryland Documents for the Classroom series of the Maryland State Archives was designed and developed by Dr. Edward C. Papenfuse and Dr. M. Mercer Neale. This packet was prepared with the assistance of Kathy Beard, Nancy Bramucci, Jim Dowdy, Roger Kizer Ball, Greg Lepore, Lynne MacAdam, John Maranto, Ryan Polk, Julie Price, R. J. Rockefeller, Emily Oland Squires, and other members of the Archives staff. MSA SC 2221-31. Publication no. 2090.

For further inquiries, please email Dr. Papenfuse at edp@mdarchives.state.md.us or call Md toll free 800-235-4045 or 410-260-6403

© Copyright 2001 Maryland State Archives.