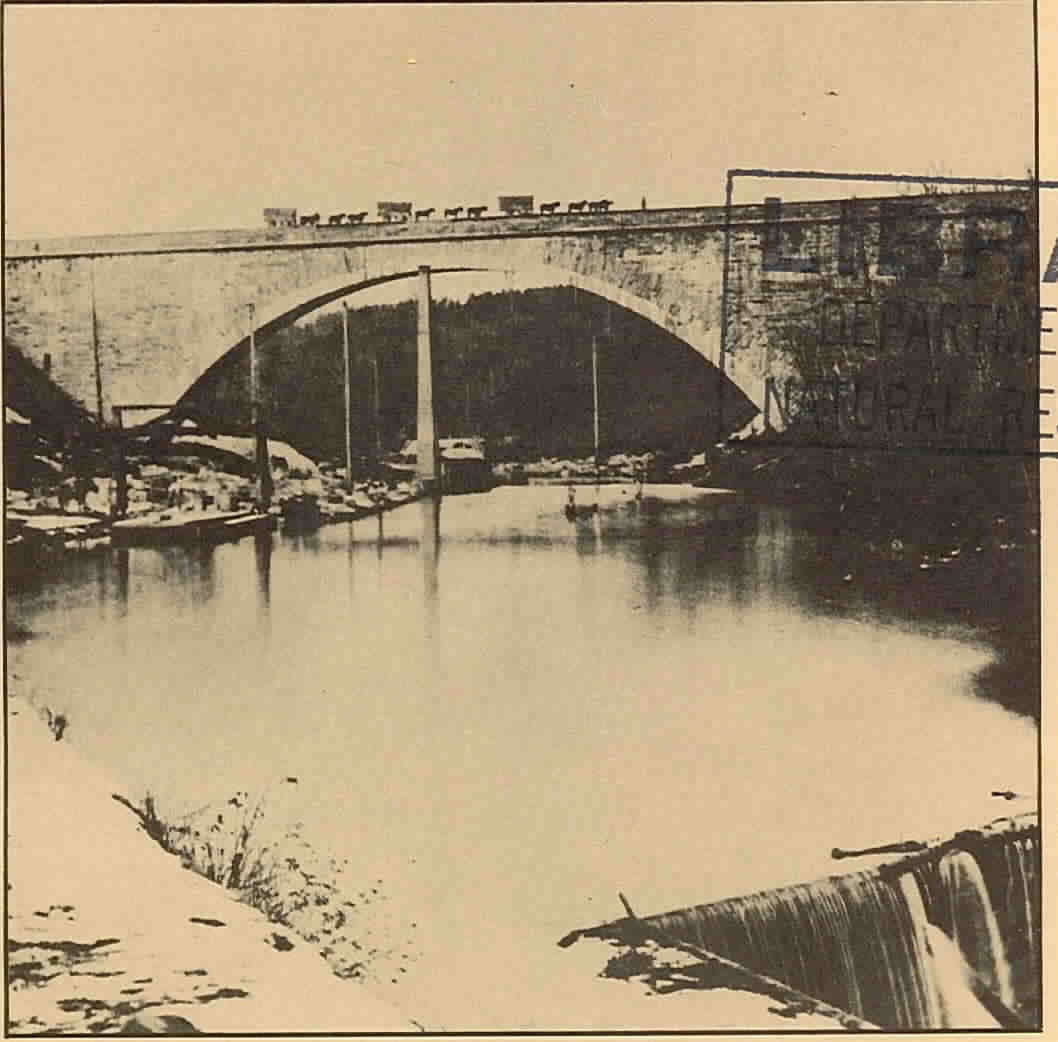

On the cover: Photograph of the Cabin John Bridge, c.

1864. The bridge was built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers as part

of the water supply system for the City of Washington, D.C., and is still

a functioning part of the Washington Aqueduct. The system currently withdraws

as much as 200 million gallons per day from the Potomac at Great Falls,

Maryland, and carries the water ten miles downstream for treatment at the

Dalecarlia Water Treatment Plant in the District of Columbia. The bridge

carries the aqueduct across Cabin John Creek in Maryland, and was at one

time the largest single-span stone arch in the Western Hemisphere. It is

now listed as a Civil Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Civil

Engineers. Photo courtesy U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

LEGAL RIGHTS IN POTOMAC WATERS

PROCEEDINGS OF A CONFERENCE

AT HARPER'S FERRY, WEST VIRGINIA

Edited by:

GARRETT POWER PROFESSOR OF

LAW UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND SCHOOL

OF LAW

Editorial Assistant:

REGINA K. WOLOSZYN

Sponsored by: INTERSTATE

COMMISSION ON

THE POTOMAC RIVER BASIN

4350 EAST WEST HIGHWAY

BETHESDA, MARYLAND 20014

and

MARYLAND DEPARTMENT OF

NATURAL RESOURCES

TAWES STATE OFFICE BUILDING

ANNAPOLIS, MARYLAND 21401

SEPTEMBER 1976 ICPRB General Publication

76-2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Interstate

Commission on the Potomac River Basin and the Maryland Department of Natural

Resources wish to express appreciation to Nathaniel P. Reed, Assistant

Secretary for Fish, Wildlife, and Parks of the United States Department

of Interior, for making available the facilities of the National Park Service's

Mather Training Center at Harper's Ferry, West Virginia, for the Potomac

Basin water law conference. Park Service personnel were most helpful in

making the symposium the success that it was. In addition, the Interstate

Commission on the Potomac River Basin is most grateful to the Maryland

Department of Natural Resources for co-sponsoring what is hoped to be the

first in a series of symposia on water rights and water law applicable

to the waters of the Potomac River Basin.

GENERAL COUNSEL'S STATEMENT As

General Counsel for the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin,

it was my responsibility to organize the water law "teach-in" on May 14,

1975 at Harper's Ferry, West Virginia. The experts selected by Professor

Garrett Power and myself were picked for their expertise in the natural

resources law field, and the opinions they expressed in their papers and

during the symposium are their own. No member of the Commission, the Commission's

staff, or myself in any way endorsed or directed what was said.

I regret that despite numerous contacts with the General

Counsel's office at the Army Corps of Engineers, Baltimore District, we

were unable to secure a paper or a speaker from the Corps. However, the

top level representation of Corps officials at the conference more than

made up for the lack of a formal presentation setting forth the rights

claimed by the United States over Potomac River waters. It is hoped that

at some time the Corps will prepare a legal brief setting out U.S. rights

in the Potomac; hopefully this could be sent out as a follow-up to this

publication.

I am most grateful to John Salyer, Esq., Assistant Corporation

Counsel of the District of Columbia, for providing on very short notice

the paper covering water rights for the District of Columbia.

The dynamic interchange among agency representatives

and industrial people with the panel of experts enlightened all, and it

is our hope that this will assist in political accommodation on water rights

issues, in place of possible long and drawn-out litigation.

All the speakers at the conference were most generous

in sharing their expertise and opinions. A good start has been made in

setting out what could be called the "base-line" of water rights law in

the Potomac River Basin.

Henry P. Stetina

FOREWORD

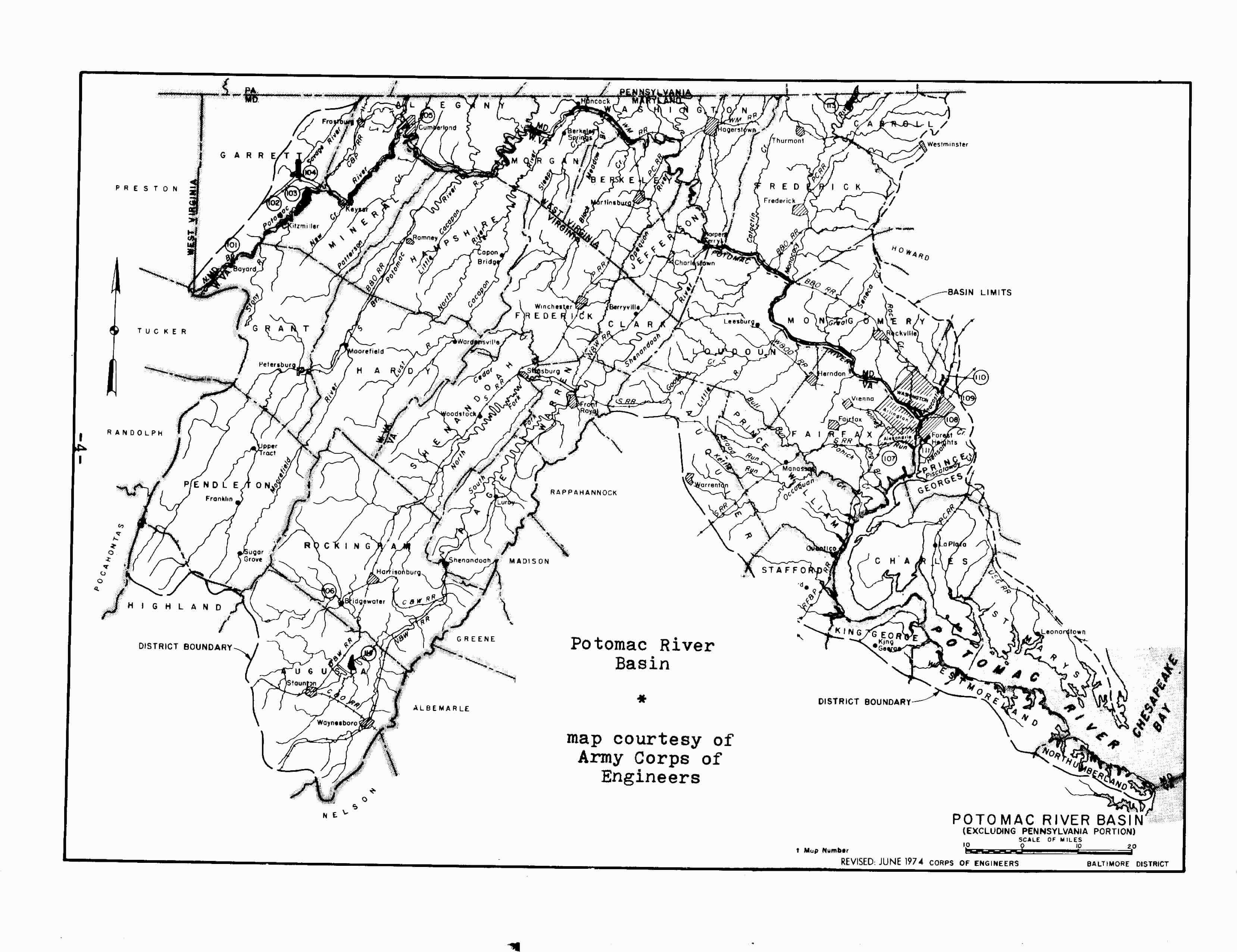

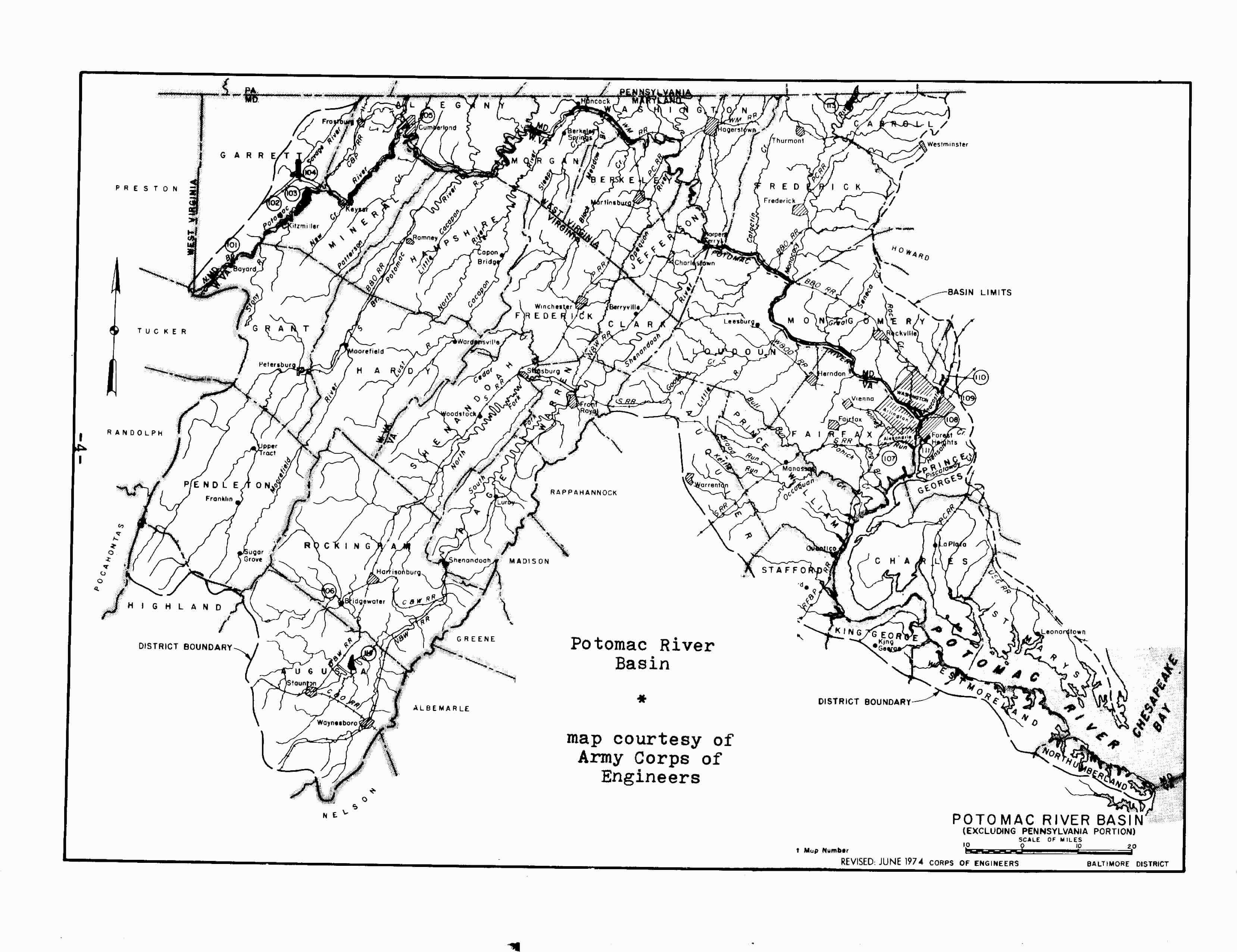

Meandering through the hills of Appalachia to the shores

of Chesapeake Bay, the Potomac River and its surrounding Basin cover 15,000

square miles of territory---including portions of West Virginia and Pennsylvania,

Virginia and Maryland, and all of the District of Columbia. The river itself,

some 400 miles in length, has for centuries been a site of recreation and

fishing and, increasingly important, a source of water.

Indeed, provision for an adequate water supply to the

sprawling Washington metropolitan area is perceived as the Basin's major

problem, one whose resolution is substantially complicated by the multiplicity

of jurisdictions concerned. The various states and the District of Columbia

have diverse laws and sometimes conflicting interests. West Virginia and

Pennsylvania presently make only minimal demands on Potomac waters, but

are in a position of advantage hydrologically, with respect to the river's

sources. For several hundred miles the Potomac serves as a boundary line

between Virginia and Maryland, but through various historical quirks and

legal interpretations, the whole river is considered within Maryland's

boundaries. Accordingly, Maryland has required the Commonwealth and citizens

of Virginia to seek its permission before making appropriations of its

water. The District of Columbia is at a peculiar disadvantage when it comes

to using the Potomac water, because the river becomes estuarine--as the

fresh water becomes with salt---before entering the District's boundaries.

-vii-

The federal government is of course likewise concerned

with the allocation of Potomac waters. Congress has ceded to the Army Corps

of Engineers specific responsibility for providing water to the District

of Columbia, in addition to the Corps' general powers as a regulator of

navigable waterways and a builder of dams.

It is against this background that a working conference

on Water Rights Affecting the Potomac Basin, sponsored jointly by the Interstate

Commission on the Potomac River Basin and the Maryland Department of Natural

Resources, was held in Harper's Ferry, West Virginia, on May 14, 1976.

The goal of the meeting was more to frame appropriate questions than to

answer them. Thus the program was designed to air differing perspectives

and to define issues---rather than to present official hard-line positions

of the jurisdictions involved.

The Proceedings which follow are a product of the conference.

The piece by Kenneth Lasson, A History of Potomac River Conflicts, provides

the historical backdrop upon which the current disputes are set. Steve

H. Hanke, in Forecasting Water Use in the Potomac River Basin, looks to

the future and predicts demands for water consumption within the Basin

area; his work also emphasizes the extent to which such demands can be

modified through alternative price strategies. Federal Authority in the

Potomac River Basin by Thomas B. Lewis outlines the federal statutory and

constitutional prerogatives. Then John Salyer, Warren K. Rich, R. Timothy

Weston, Denis J. Brion and Patrick C. McGinley look respectively to the

relevant laws and institutions of the District of Columbia, Maryland, Pennsylvania,

Virginia and West Virginia.

-viii- Taken together, the

papers pose the water supply issues facing the Potomac Basin, ranging from

general to specific: ---Is there a need for an agency with overall water

resource planning and management powers in the Potomac Basin? If so, how

should it be organized and financed? ---How should water be priced in the

Washington metropolitan area? Is the area in fact "water short"? If so,

is the problem one of base flow, peak demand, or both? ---Should the dams

and reservoirs proposed by the Army Corps of Engineers for Bloomington,

Sixes Bridge and Verona be constructed? If so, when? ---Do the States of

West Virginia and Pennsylvania have the power to divert Potomac waters

into other basins? If so, are there any legal constraints on such authority

and what are they? ---Under present law, must Virginia and the Corps of

Engineers obtain permission from the State of Maryland before appropriating

Potomac waters? If so, can Maryland prerogatives be diminished without

its consent? ---Must specific statutes of the various states be changed

in order to achieve an economically efficient allocation of water resources?

If so, which laws need be modified? The papers which follow analyze these

questions in some detail. A great deal more work may provide some answers.

September 1, 1976

Garrett Power

-ix-

PAPERS PRESENTED

BY

CONFERENCE SPEAKERS

A HISTORY OF POTOMAC RIVER CONFLICTS

Kenneth Lasson

We now know. the Potomac River as a 383-mile waterway

which forms a clear interstate boundary between Maryland and Virginia on

the one hand, and Maryland and West Virginia on the other. l

It hasn't always been that simple. Just where the Potomac is, and to whom

it belongs, have been in dispute for at least 350 years.

I. Where and Whose?

We aren't certain how the Indians divided or decided their

rights to the river, but the earliest recorded controversies over ownership

and jurisdiction arose from conflicting royal charters given to the Virginia

Company and to Lord Baltimore. The former received three successive charters

from the English Crown; all three documents extended the boundaries of

Virginia north and south of the present state, to include all of Maryland,

parts of Pennsylvania, and parts of North Carolina. The terms of the second

charter (granted by King James I on May 23, 1609) gave the Virginia Company

all territory from Point Comfort 200 miles to the north and 200 miles to

the south. 2

It was on June 20th of 1632 that King Charles I granted

to Lord Baltimore a tract of land on the Atlantic Coast of North America,

which was to become the proprietary colony of Maryland. The southern boundary

(west of the Chesapeake Bay) was specified by the charter--which was written

in Latin. Although some controversy exists over the translation, a generally

accepted version of the boundary extends

-2 -

the northern line of Maryland along the 40th parallel

of latitude, to a point where the meridian of longitude which passes through

the "first fountain" of the Potomac intersects this parallel. The meridian

thus designated forms the western boundary of Maryland.

The boundary description continues:

Unto the true meridian of the first Fountain of the

River of Pattowmack, thence verging toward the South, unto the further

bank of the said River, and following the same on the West and South, unto

a certain Place, called Cinquack, situate near the mouth of the said River,

where it disembogues [sic] into the foresaid Bay of Chesapeake. The charter

appears to grant possession of the entire Potomac to Maryland: that is,

the western boundary line of Maryland extends from the Pennsylvania border

south across the river to the "further bank"--or south shore of the river.3

Now, the King and his Council had absolute authority over

the American colonies, and they could and did change boundaries at their

royal pleasure. That the King could carve out such a large tract of land

from Virginia was not disputed, nor was his power to include in that grant

the entire Potomac. But the specific terms and intentions of the grant

have long been argued.

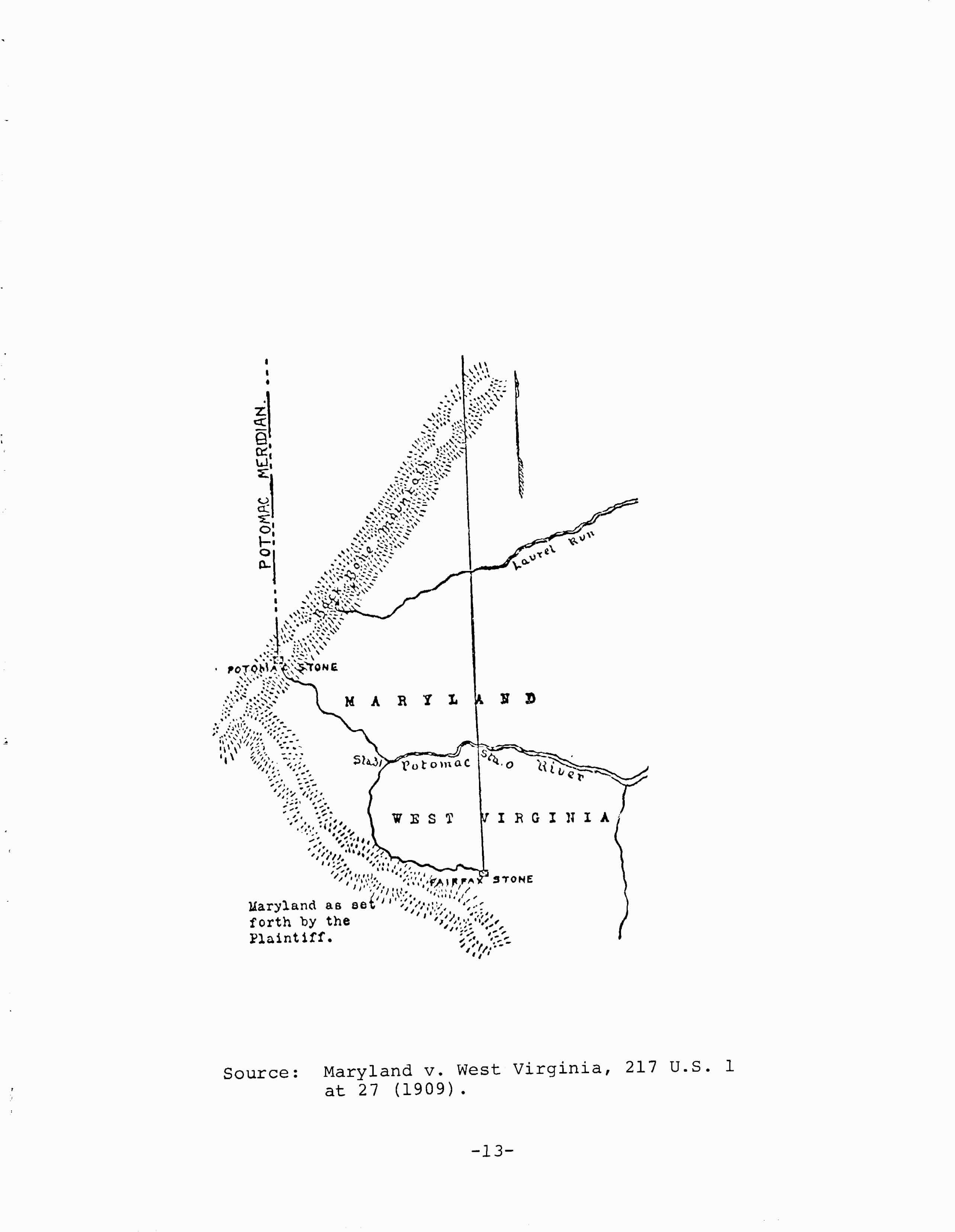

In the early 17th century the territory wherein the source

of the Potomac lies was unexplored wilderness. The river's length, source,

and course were unknown. If, at its source, the Potomac were headed in

a northeasterly direction before it turned to its primary southeasterly

flow, or if the Potomac extended north of the 40th parallel, it could be

contended that the terms of the grant called for the river to lie outside

of the boundaries of Maryland (see illustrations). In

-3-

addition, as one follows the Potomac inland, several

large branches emanate from the river's trunk, such as the Shenandoah (with

its South Fork and North Fork) and the South Branch. At the time it was

uncertain which one of these large branches was to be considered the Potomac

River; thus the jurisdiction over a large expanse of territory was unclear.

To add to the controversy over ownership rights, King

James II (in September of 1688) made a separate grant of the Northern Neck

of Virginia to Thomas (Lord) Culpeper, whose heir (Lord Fairfax) eventually

took possession. The royal charter specifically included the Potomac within

the grant which was bounded by: "Patawomerck Rivers . . . together with

the said rivers themselves and all the islands within the outermost banks

thereof . . ."4

But the earliest disputes involving the Potomac were not

over ownership of the river itself. There was little reason to contest

such rights. Commerce was limited. Established common law rules over navigable

rivers prevailed, permitting all interested parties access to the water.

Moreover, demand for seafood was confined to local consumption by the slow

modes of transportation at that time.

The early disputes centered more around ownership of contiguous

land that would be determined by the location of the Potomac. In the 1730's

Governor Gooch of Virginia and Lord Fairfax claimed much of the same western

territory. Maryland joined the fray by claiming all the land north of the

Shenandoah River (on the ground that it was the main branch of the Potomac

River). Virginia's Gooch contended that the Cahongartooten River was the

main branch of the Potomac and the

-5-

boundary of Maryland---giving him more land to the west

and south. 5

Maryland did not vigorously prosecute its claim, and

acquiesced in the settlement between Governor Gooch and Lord Fairfax. This

compromise resulted from an order by the King that Gooch and Fairfax appoint

commissioners for the purpose of deciding the boundary. The commission

adopted the North Branch, then known as the Cohaungoruton, as the main

stream of the Potomac River. A marker (known as the Fairfax Stone) was

planted at the first fountain of the North Branch. The designation of this

spring as the source of the Potomac was approved by the Virginia Assembly

and the King in Council in 1748.

Although this settlement established the first fountain

of the Potomac and the western boundary of Maryland, it left open the ultimate

question, ownership of the river itself.

In 1776, when the colonies were declaring their independence,

Virginia (on June 29th) adopted its first Constitution, which provided:

The territories contained within the charters

erecting the colonies of Maryland . . . are hereby ceded, released and

forever confirmed to the people of those colonies . . . with all the rights

of property, jurisdiction, and government . . . except the free navigation

and use of the rivers Potomac and Pocomoke, with the property of the Virginia

shore . . . and all improvements which have been or shall be made thereon.

Virginia thus unilaterally relinquished all claim to Maryland

lands, but reserved the rights of free navigation and use of the Potomac

and the riparian rights of the landowners of the Virginia shore.

Maryland, as might be suspected, did not accept Virginia's

claim to rights in the Potomac River. Under the Articles of Confederation,

-6-

serious friction began to develop between the two states

over navigation and use of both the Chesapeake Bay and the Potomac. Several

joint conferences in the late 1770's were unable to settle the differences

between them.

In June of 1784, theVirginia General Assembly resolved

to appoint George Mason, Edmund Randolph, James Madison, Jr., and Alexander

Henderson as commissioners, and invited Maryland to send its own commissioners

to meet and "frame such liberal and equitable regulations" as may be necessary.6

The Maryland Legislature, greatly concerned about Virginia's collecting

tolls from ships passing through the Virginia Capes of the Chesapeake,

responded with a resolution (January 18, 1785) appointing Thomas Johnson,

Thomas Stone, Samuel Chase, and Daniel of St. Thomas Jenifer commissioners,

and charging them with "settling the navigation and jurisdiction over that

part of the bay of Chesapeake which lies within the limits of Virginia,

and over the rivers Potomac and Pocomoke." 7

II. The Compact of 1785

The joint commission met at Mount Vernon in March of 1785,

and succeeded in drafting a compact which was accepted and confirmed by

the legislatures of both states. The Compact of 1785 provided substantially

as follows:

Article I. Virginia disclaimed the right to charge

tolls of vessels passing through the Chesapeake Bay Capes bound to or from

Maryland; the Chesapeake Bay was to be considered a common highway.

Article II. Maryland conferred the same privileges

on vessels trading to or from Virginia.

Article III. War vessels of either state were

to be free of all charges.

_7- Article IV and V. Commerce

between the citizens of both states in their own produce was to be permitted

subject to obtaining a permit from a naval officer.

Article VI. The Potomac River was to be common

highway.

Article VII. Riparian rights and fishing rights

were to be common to citizens of both states.

Article VIII. All laws and regulations for the

preservation of fish, navigation, and quarantine were to be made with the

consent of. both states.

Article IX. The expense of maintaining navigational

aids on the Chesapeake and Potomac was to be shared by both states.

Article X and XI. Both states were to have concurrent

jurisdiction over criminal and civil matters on the Potomac.

Article XII. Citizens with property in both states

had liberty to transport their produce duty free.

Article XIII. The Compact was to be confirmed

and ratified by the legislatures of both states and never to be repealed

or altered by either without the consent of the other.

The Compact of 1785 succeeded in laying the groundwork

for cooperation between Maryland and Virginia concerning the regulation

of activity on the Potomac River. But the ownership of the river remained

unresolved. Maryland still claimed rights to the high-water mark on the

south shore; Virginia claimed to the center of the river. 8

Without deciding the boundary, Article VII ("The citizens of each state

respectively shall have full property in the shores of Patowmack river

adjoining their lands") limited Maryland's claim to the low-water mark

of the Virginia shore.

During the next hundred years, in continuing attempts

to settle

-8-

the boundary, numerous resolutions were passed and commissions

created by both Maryland and Virginia---sometimes acting individually and

sometimes together. Perhaps any urgency to establish the exact boundary

between the states was diminished by the apparent effectiveness of the

Compact of 1785 in providing a stable administration over the river. Besides

the Compact, Virginia and Maryland were cooperating on improving the navigation

of the upper Potomac. They jointly chartered the Potomac Company, and its

successor, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Company. 9 But ownership

rights were still sought and unresolved. In 1795 the Maryland General Assembly

nominated William Pinkney, William Cooke, and Philip B. Key to serve as

boundary commissioners. 10 This overture, as well as similar

efforts in 1801 and 1810, met with little success. Once again, in 1818,

the Maryland Legislature attempted to establish a joint commission to resolve

the boundary controversy. The Virginia Assembly responded four years later,

in 1822. But a divergency in the instructions given the commissioners from

the two states led to a breakdown in negotiations which proved fruitless.

In 1825, a Maryland act which proposed that the Governor of Delaware serve

as an umpire went unreciprocated. An 1833 act of the Virginia Assembly

was ignored by Maryland. 11

Not until 1856 did a joint Maryland/Virginia commission

actually begin to negotiate. With this commission still in being, the Virginia

General Assembly passed a resolution on March 10, 1860, for Governor Letcher

to send Colonel McDonald to England, for the purpose of securing evidence

by which the true boundary between Virginia and her neighbors could be

established. Colonel McDonald visited England, and

-9-

returned with nine volumes of manuscripts and one book

of rare maps. The Civil War brought an end to this attempt to define the

true boundary.

III. The Black-Jenkins Award

A joint commission was re-established in 1872, but it

was disbanded in 1873 without success. 12 Finally, in 1874,

the two states, hoping to avoid having the boundary question determined

by the United States Supreme Court, agreed to submit to binding arbitration.

The states selected two arbitrators who in turn selected a third. The former

two were Jeremiah S. Black of Pennsylvania---a former Chief Justice of

the Pennsylvania Supreme Court and the United States Attorney General and

Secretary of State under President Buchanan ---and William A. Graham of

North Carolina, a former Governor and United States Senator. They chose

Charles J. Jenkins, a former Governor of Georgia and Justice of the Georgia

Supreme Court, as the third referee. When Graham died, Black and Jenkins

were reappointed, and James B. Beck of Kentucky was added.

The states were represented before the arbitrators by

counsel, who presented arguments. Maryland again claimed the Potomac River

to the high-water mark on the south shore; Virginia claimed the river to

the north shore. Unanimously, the arbitrators found that the Potomac River

belonged to Maryland as far as the low-water mark on the south shore. They

prepared a map and an award which described the boundary in part:

Beginning at a point on the Potomac River where

the line between Virginia and West Virginia strikes the said river at the

low-water mark, and thence following the meanderings of said river by the

low-water mark to Smith's Point, at or near the mouth of the Potomac .

. . .

-10-

The arbitrators had based their award on the original

charter to Maryland, which they thought included the Potomac River to the

high-water mark. However, by prescription, Virginia's continued use and

jurisdiction over the land on her shore to the low-water mark from the

time she first occupied the territory, should give it rights in the land

on its shore to the low-water mark. The arbitrators' assignment did not

end with determining the boundary on the Potomac, but extended across the

Chesapeake Bay to the Eastern Shore. To the award presented on the Eastern

Shore, Beck dissented. The award of the majority was approved by the legislatures

of both states and has come to be known as the Black-Jenkins Award of 1877.13

In 1899, differences arose as to the boundary in the vicinity

of Hog Island, which Maryland claimed as part of the Potomac. Governor

Lee of Virginia and Governor Jackson of Maryland requested assistance from

the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, which assigned Henry L. Whiting

to make a determination. Whiting concluded that the lowwater line should

not follow the indentations of creeks and bays, but should run from headland

to headland. By this reasoning, Hog Island did not lie in the Potomac,

but "on" it; it was an island, by virtue of its being bounded on one side

by the Potomac and on its other sides by inland creeks. Whiting's decision

that the island belonged to Virginia reaffirmed the Award of 1877.14

IV. The Mathews-Nelson Survey

The last vestige of controversy, surrounding the indentations

along which the boundary did not run, was eliminated by the MathewsNelson

Survey of 1928. Except for several very minor deviations,

-11-

this survey reaffirmed the Award of 1877. It was approved

by the legislatures of both states (Virginia ACTS ch. 477 of 1928 and Maryland

ACTS ch. 50 of 1929).

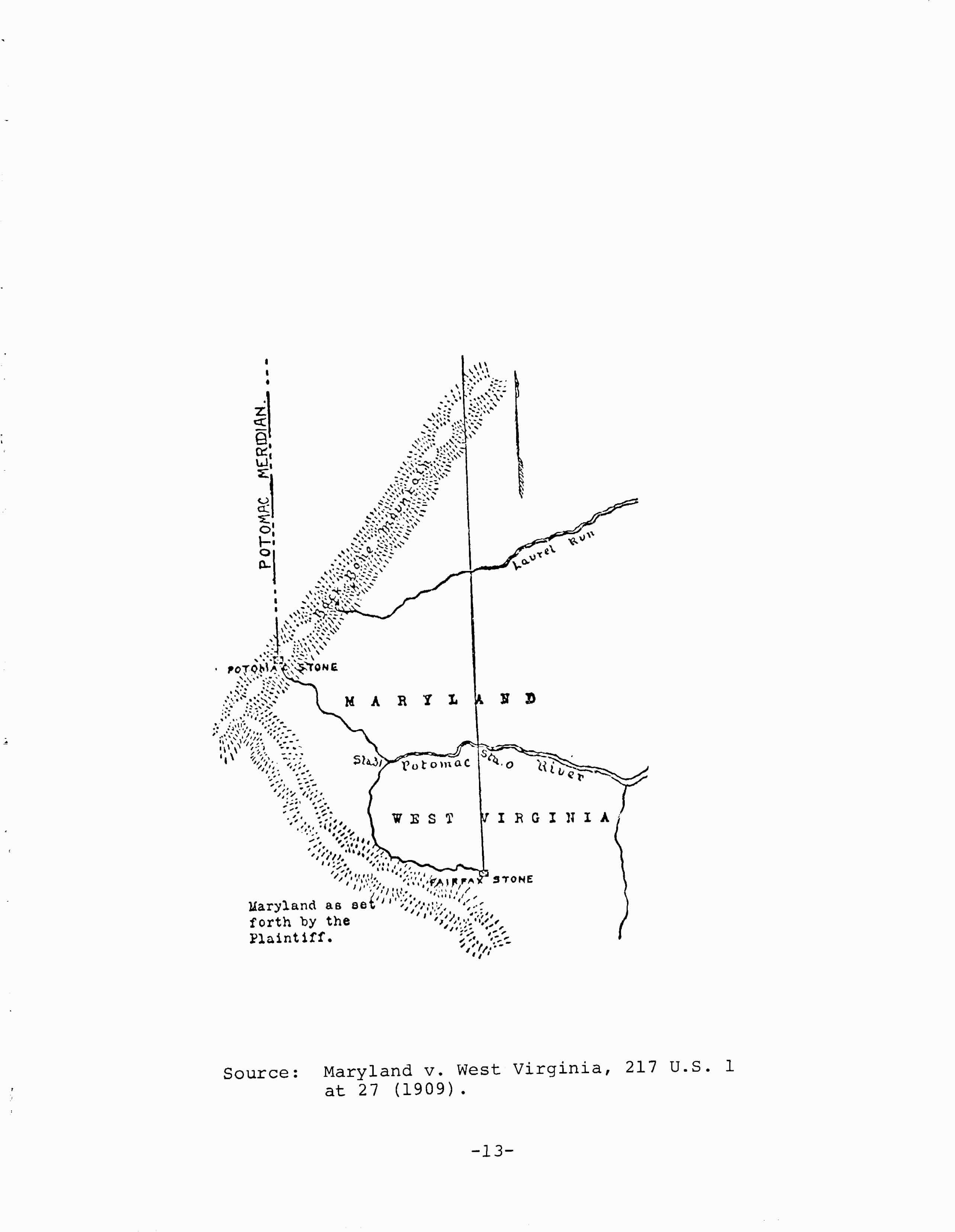

V. Maryland Versus West Virginia

When West Virginia broke away from Virginia during the

Civil War, it succeeded to the rights and obligations of Virginia in the

Potomac River. The status of West Virginia's Potomac border with Maryland

was still as unclear as Virginia's had once been. In 1910, Maryland and

West Virginia found themselves arguing in front of the United States Supreme

Court to determine the boundaries between them. In its Bill in Equity,

Maryland claimed that her territories extended to the south shore of the

South Branch of the Potomac, rather than the North Branch as determined

by the Fairfax Stone in 1746. West Virginia answered that Virginia has

asserted and exercised jurisdiction over the territory south of the Fairfax

Stone---at the North Branch---from 1746 until 1852, when Maryland had asserted

a claim to the first fountain of the South Branch. Furthermore, argued

West Virginia, the geographical features of the river indicate that the

North Branch is the main stream of the Potomac. At the juncture of the

North and South Branches, the course of the North Branch runs straight

prior to and flowing from the juncture. The South Branch, on the other

hand, joins the river at an angle. The flow of the North Branch is more

dominant than the South Branch.

Maryland did not press this point with the Court. Its

main concern was the location of the first fountain of the North Branch

of the Potomac. Maryland rejected the theory that Fairfax Run (as designated

-12-

by the Fairfax Stone) was the first fountain of the North

Branch; it contended that Potomac Spring, which had just recently been

discovered, was the true first fountain. Maryland argued that the course

of Potomac Spring was more consistent with the general course of the river

than Fairfax Spring, and that Potomac Spring flowed year-round, whereas

Fairfax Spring tended to slack off during dry periods. As the source of

Potomac Spring was about one and one-quarter miles to the west of the Fairfax

Stone, a determination that Potomac Spring was a point on the Maryland/West

Virginia border would shift a tract of West Virginia land one and one-quarter

miles by 37 miles into Maryland's jurisdiction.

The Supreme Court held that the border should remain as

fixed by the Fairfax Stone. Although Maryland had not been a party to the

dispute which led to the erection of the Fairfax Stone, it had recognized

the stone as a boundary marker. When Garrett County was created in 1872,

Maryland had designated the Fairfax Stone as the southwest point of the

county. (See Maryland v. West Virginia, 217 U.S. 1 [1910].)

West Virginia claimed ownership of the Potomac River on

the basis of Lord Culpeper's grant of the Northern Neck (supra page 2).

The Court held that West Virginia's claim was ineffective in light of the

Arbitration Award of 1877. In a supplementary opinion, the Court held that

the boundary on the Potomac should be the low-water mark of the south shore

as determined by the Award of 1877. (See 217 U.S. 577, 587.)

-14- VI. The District of

Columbia

When Maryland and Virginia ceded part of their territory

to the federal government for the District of Columbia,15 they

necessarily included their respective rights in the Potomac River. 16

At that time, the District had rights to both sides of the Potomac. But

in 1846 the United States returned the land ceded by Virginia to the state,

17

opening

again the question of the exact border between the District and Virginia.

The issue was settled by judicial decisions involving private parties.

VII. Judicial Interpretation of the Compact of 1785

Criminal jurisdiction on the Potomac River, for example,

was determined to vest in the local courts of either Virginia or the District,

and not with the federal government. In Ex parte Ballinger, 88 F.

781 (D. Va. 1882), the defendant was charged in federal court with the

crime of piracy for the act of robbing a passenger on a ferryboat between

the District and Alexandria. Although the crime was committed on tidewater,

the court held that where tidewater is already under the jurisdiction of

local courts, federal courts have no jurisdiction. The defendant was discharged

on a writ of habeus corpus.

In Marine Railway & Coal Co. v. United States, 257

U.S. 47 (1921), the United States had conducted a dredging operation to

improve the channel for navigation. A sea wall was built on the riverbed

between two headlands of a shallow cove on the Virginia side of the river

adjacent to the City of Alexandria. The material dredged was deposited

behind this wall and created a new strip of land abutting land, formerly

riverfront land, owned by the Railway. The government erected a fence

-15-

separating the newly made land from the original land.

The Railway removed the fence and claimed the new land as its own. The

Supreme Court held that the United States (District of Columbia) held title

to the land beneath the water and retained title to that land when it was

reclaimed. The Court distinguished this newly reclaimed land from the reclaimed

land upon which many city blocks of Alexandria rest and to which Virginia

by long-standing occupation and administration has acquired jurisdiction

by prescription. The Court said it was immaterial that the Railway lost

its riparian rights, because riparian rights are subject to navigation

and projects necessary for navigation have priority.

In Herald v. United States, 284 F. 927 (App. D.C. 1922),

the defendant was convicted of unlawfully fishing with a dip net in the

Potomac River within the District of Columbia. He had operated his net

as he stood on the rocks between the high-water and low-water marks of

the Virginia shore. Affirming the conviction, the Supreme Court held that

the royal grant from Charles I to Lord Baltimore established the true boundary

on the Potomac to be the high-water mark. The Court declared that the Award

of 1877 between Maryland and Virginia did not affect the boundary of the

District.

The defendant in Herald also argued that regardless of

the boundary, the Compact of 1785 secured to him the right to fish in the

Potomac unless Virginia consented to the law prohibiting or regulating

fishing. The Court held that the Compact was not effective between the

District and Virginia. When the District held the land on both sides of

the Potomac, the Compact was perforce abrogated. The recession by the

-16-

United States to Virginia of its land bordering the Potomac

did not revive the Compact, for the U.S. never assented to its terms. A

similar result was reached in Evans y. United States, 31 App. D.C. 544

(1908) under a similar set of facts.

In Smoot Sand & Gravel Corp. v. Washington Airport,

Inc., 283 U.S. 348 (1931), rev'g.,44 F.2d 342 (4th Cir. 1930), the United

States Supreme Court agreed that the boundary between the District and

Virginia was at the high-water mark on the Virginia shore. This decision

allowed the Smoot Corporation to continue excavating to the highwater mark

of land claimed by the Airport. The Court reasoned that Maryland conveyed

to the District of Columbia the land to the highwater mark which the King

had granted to Lord Baltimore, and that nothing had occurred to change

that grant. The Court said that the decision in Maryland v. West Virginia,

supra, which was based on prescriptive rights, was not applicable to this

case.

Although the high-water mark is the recognized boundary

between the District and Virginia, in the vicinity of the harbor of Alexandria,

the fluctuations of the river height on vertical sea walls and piers have

no effect on the horizontal boundary. Therefore, Congress designated the

boundary in the City of Alexandria to be the established pier line. The

boundary will change as the pier line changes. 18 When the United

States sued to "quiet title to land to all fast and submerged lands . .

. that lie along the waterfront of the city of Alexandria," the Federal

District Court dismissed the action for lack of jurisdiction over land

not within the boundaries of its district

(which lies within the District of Columbia). United

States v. Herbert Bryant, Inc., 386 F. Supp. 1287 (D.D.C. 1974).

-17-

The Mount Vernon Conference which had produced the Compact

of 1785 between Maryland and Virginia was held under such cordial and cooperative

conditions that a regional conference was proposed to discuss problems

that concerned several of the middle-Atlantic and southern states. The

result of this proposal was the convention in Philadelphia that drafted

a new Constitution for the United States. Adoption of the Constitution

rendered several of the clauses of the Compact of 1785 as either ineffective

or subject to the Constitution. Section 8 of Article I gave Congress the

power to regulate commerce among the several states. Section 9 of Article

I prohibited one state from imposing duties on vessels bound to or from

another state.

Except for those constitutional limitations, however,

the Compact remained in full force and effect until it was superseded by

the Compact of 1958. In 1894, the United States Supreme Court in a lengthy

dictum in Wharton v. Wise, 153 U.S. 155, aff'g. sub nom. Ex parte Marsh,

57 F. 719 (E.D.Va.), declared that the Compact was binding on the States

of Maryland and Virginia. Nevertheless, the Compact in the instant case,

which involved a Maryland oysterman prosecuted in the Virginia courts for

violating a Virginia law in the Virginia portion of the Chesapeake Bay,

was of no effect. The Court heard arguments that the Compact violated both

Article 6 of the Articles of Confederation (which had provided that the

consent of Congress was required before any state could enter into a "treaty,

confederation, or alliance") and Section 10, Article 1 of the United States

Constitution (which requires Congressional consent before a state may "enter

into any agreement or compact with another State"). The Court said

-18-

that these provisions were directed toward the "formation

of any combination tending to the increase of political power in the States,

which may encroach upon . . . the just supremacy of the United States."

The Compact of 1785 was not of such a nature. In any event, the Constitutional

provision referred only to future compacts and agreements, not to existing

compacts. Furthermore, the two states still considered the Compact effective,

for the 1874 Acts of b.oth states designating the arbitrators of the boundary

reserved all rights and privileges granted by the Compact of 1785.

Although the citizens of Maryland and Virginia were subject

to all of the obligations and entitled to all of the benefits of the Compact

of 1785, the states, and not the people, had been parties to the Compact.

This fact was important in deciding City of Georgetown v. Alexandria Canal

Co., 37 U.S. (12 Pet.) 91 (1838). The Alexandria Canal Co. in accordance

with a Congressional charter, began the construction of an aqueduct across

the Potomac immediately above Georgetown, whose officials claimed that

the construction impaired the rights of free navigation secured to their

citizens by the Compact of 1785. The Supreme Court held that when Maryland

and Virginia ceded territory to Congress for the District of Columbia,

Congress acquired the power to do what Maryland and Virginia could do by

their joint will. As Maryland and Virginia by joint action could modify

or even abrogate the Compact of 1785, so too did Congress now have the

same power. An Act of Congress gave the Canal Company the authority to

construct the aqueduct across the Potomac. As long as the company does

not exceed this authority, it may continue its operations.

-19 VIII. Fishing Rights

and Oyster Wars

Although the Compact plainly regulates the relationship

between Maryland and Virginia concerning the Potomac River, the scope of

the document as it relates to the citizens of each state has been questioned.

In 1926 a resident of West Virginia was convicted by a Maryland court for

fishing with a fish pot in violation of the provisions of a Maryland statute

that prohibited fish pots above tidal waters. West Virginia had not consented

to this provision. The defendant raised Article VIII of the Compact which

requires all laws and regulations concerning the preservation of fish on

the Potomac to be approved by both states. The Maryland Court of Appeals

in Middlekauff v. Le Compte, 149 Md. 621, 132 A. 48 (1926), held that the

Compact did not extend to the upper, non-navigable portions of the Potomac.

The Court based its opinion on the history of the origin of the Compact,

which had been spawned in an effort to solve navigational problems. The

Court followed the famous Binney's Case, 2 Bland 99 (Md. Ch. 1829), which

held that the various terms of the Compact referred only to the navigable

waters of the Potomac.

This interpretation of the Compact has continued to the

present day. However, after two West Virginia fishermen were fined for

fishing in the Potomac without Maryland licenses in 1937, the Governor

of West Virginia protested that the Compact of 1785 gave West Virginia

residents the right to fish in the Potomac. Maryland responded that the

Compact applies only to navigable waters. A conference of the Maryland

and West Virginia governors, where Maryland proposed to allow West Virginia

residents the right to fish in the Potomac in exchange

-20-

for the right of Maryland residents to fish in the first

half-mile of the Potomac's tributaries, would not settle the dispute. West

Virginia urged taking the matter to the United States Supreme Court, but

agreed that the fishing fines here would not make for a suitable test case.

19

In the decree settling the boundary dispute between Maryland

and West Virginia, the Supreme Court had indicated that nothing was to

be construed as abrogating the Compact of 1785 which was applicable to

West Virginia. Maryland v. West Virginia, 217 U.S. 577, 585 (1910). The

applicability of the Compact to West Virginia, however, is weakened by

Maryland's Compact of 1958 with Virginia.

Maryland courts have ruled that where the Compact is applicable,

Virginia's consent to fishing laws is a prerequisite to enforcement. In

State v. Hoofman, 9 Md. 28 (1856), a man was indicted for fishing with

gill nets in the Potomac River contrary to a Maryland statute. His demurrer

was sustained on the basis that Virginia had not consented to this law

in accordance with the Compact of 1785. Maryland argued that acquiescence

by Virginia was tantamount to consent, and that Virginia had not complained

about Maryland's enforcement, but those arguments were considered insufficient

to reverse the trial court.

The concurrent jurisdiction over the fishing laws on the

Potomac carried with it the right to enforce those laws. A Maryland citizen

had been convicted by a Fairfax County, Virginia court of violating a fishing

provision of the Virginia Code that had been approved by Maryland. He had

been apprehended opposite Indian Head, Maryland, near the Virginia shore.

He argued that Article X of the Compact, dealing

-21-

with crimes and offenses on the Potomac, provided that

citizens of Maryland charged with criminal offenses were to be tried in

Maryland courts---Virginia citizens, in Virginia courts. The Supreme Court

of Virginia held in this case (Hendricks v. Commonwealth, 75 Va. 934 [1882])

that Article VIII applied to the enactment and enforcement of fishing laws,

and that Article X applied to general criminal jurisdiction that was not

specifically covered elsewhere in the Compact.

The right of a Virginia citizen charged with a criminal

offense on the Potomac to be tried in his home state has likewise been

eliminated. In Barnes v. State, 186 Md. 287, 47 A.2d 50 (1946), cert. denied,

329 U.S. 754,20 a Virginia citizen was convicted in the Prince Georges

County Circuit Court of raping another Virginia citizen on a steamboat

on the Potomac. The defendant appealed, challenging the trial court's jurisdiction.

He argued that Article X of the Compact of 1785 provided that only Virginia

courts could try a Virginia citizen for a crime committed on the Potomac.

The Maryland Court of Appeals re-examined the history behing the Compact.

It recalled that in 1785 boundary disputes between Maryland and Virginia

had given rise to a conflict of jurisdiction over the Potomac River, Maryland

claiming all of the river and Virginia claiming to the center. However,

the boundary settlement of 1877, establishing that Maryland owned all of

the Potomac to the low-water mark on the Virginia shore, vested full and

exclusive criminal jurisdiction over the Potomac in Maryland. Maryland's

claim to full and exclusive criminal jurisdiction was further supported

by the state's enactment of laws dealing with offenses on Potomac steamboats;

Virginia has

-22-

passed no such laws. The provisions in Article X for concurrent

criminal jurisdiction apply only in areas of uncertain jurisdiction, doubts

which have been few and far between since the Black-Jenkins Award of 1877.

The riparian rights granted by Article VII of the Compact

of 1785 to the owners of riverfront property belong to both Maryland and

Virginia landowners. In Bostick v. Smoot Sand & Gravel Corp. 260 F.2d

534 (4th Cir. 1958), rev'g. 154 F. Supp. 744 (D. Md.), the Smoot Corporation,

with permits from both the Army Corps of Engineers and the Maryland Board

of Public Works, began dredging operations in front of land owned by Virginia

residents. Although there is no common law right of riparian owners to

the sand and gravel below the low-water mark, Maryland by statute had granted

to riparian owners the exclusive right to remove subsurface minerals between

the high-water mark and the outer channel, so long as they did not interfere

with the fish and oyster laws. The court found that the Smoot Corporation

was, therefore, operating in violation of the riparian owners' rights,

which were also applicable to Virginia landowners.

In a dictum in Ex parte Marsh (supra, at 723), the court

remarked: "There are oysters in the more brackish waters near the mouth,

but the oyster interests of the Potomac have always been very inconsiderable."

The scarcity of oysters on the Potomac kept conflicts among the various

Chesapeake Bay oyster factions at a minimum.

In the 1870's and 80's, however, skirmishes broke out

between the tongers and the dredgers on the Potomac. 21 This was not just

a dispute between Marylanders and Virginians. The controversy involved

-23-

rivermen on the one hand, and Virginians, "Easternshoreners",

and Baltimorians on the other. The primary reason for the termination of

this "oyster war" was probably the river's dwindling supply of oysters.

The oyster industry on the Potomac continued relatively

peaceful until the end of World War II. Skyrocketing oyster prices renewed

the interests of outsiders in the Potomac oyster beds. Intense industrial

activity during the war, luring watermen away from oystering, had allowed

the oyster beds to replenish themselves. Maryland and Virginia have long

had substantial differences of opinion on how oystering should be conducted.

Virginia believes in the long-term leasing of oyster beds for exclusive

exploitation---by any method of harvesting. Maryland believes in public

beds, which can be harvested by tonging only. But Virginia power dredgers

frequently conducted illicit dredging operations.

In 1945 Virginia refused to join Maryland in a special

joint committee to study and examine the Potomac oyster problem. 22 No

agreement, as required by Article VIII of the Compact of 1785, could be

reached concerning the regulation of oystering on the Potomac. In 1950

a Maryland decision to begin bringing Virginia violators to trial in Maryland

courts brought a strong protest from the Governor of Virginia. A shooting

war erupted between Maryland's Tidewater Fisheries Commission Police and

the Virginia dredgers. The shootings, combined with a new Maryland policy

of imposing an export tax on Virginia oystermen (which Virginia claimed

violated the Compact), led to a deterioration of relations between the

two states and of the effective administration of the laws governing the

operations on the

-24-

river. Maryland accused Virginia of violating the Compact

by not prosecuting oyster offenders. 23

In 1957 Governor Theodore McKeldin signed a bill passed

by the Maryland Assembly to abrogate the Compact.24 Virginia

immediately appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States, which referred

the case to Stanley F. Reed, the retired Justice, for

settlement. (See Virginia v. Maryland, 355 U.S. 946 [1958],)25

Under Justice Reed's auspices, a new agreement (to be

known as the Potomac River Compact of 1958) was drafted. 26

This agreement specifically superseded the Compact of 1785. It also provided

that Virginia must recognize Maryland as the owner of the Potomac River

as laid out in the Mathews-Nelson Survey of 1927, that all existing riparian

rights of Article VII of the 1785 Compact are to be preserved, and that

a Potomac River Fisheries Commission (PRFC) was to be created.

The Compact of 1958 outlined the organization, power,

and authority of the PRFC, which has territorial jurisdiction over the

Potomac River from the Chesapeake Bay to the D. C. line, as well as jurisdiction

over the taking of all finfish, crabs, oysters, and clams. The PRFC is

composed of three commissioners from each state. The PRFC will make no

distinction between Maryland and Virginia residents. Maryland and Virginia

are to enforce jointly the regulations of the PRFC.

Maryland's watermen lobbied against approval of the new

Compact as a relinquishment of the state's control over the river. The

Maryland Assembly approved the Compact, but the watermen were able to force

a state-wide referendum. After the voters approved the Compact, the watermen

challenged the referendum in court. They lost. In Dutton v.

-25-

Tawes, 225 Md. 484, 171 A.2d 688 (1961), the Maryland

Court of Appeals held that minor, unintentional irregularities of publication

were not enough reason to overturn the referendum, and that making a Compact

was not an unconstitutional legislative abdication, but an exercise of

government.

Shortly after the PRFC was established, the Baltimore

Sun (on January 10, 1964) reported that Virginia was dominating the agency.

Governor Tawes called in and criticized Maryland's three commissioners

for allowing the PRFC's temporary headquarters in Virginia to take on the

appearance of a permanent headquarters---to the detriment of Maryland watermen

who must go there to obtain licenses---for letting all funds of the PRFC

to be deposited in a Virginia bank, and for permitting Virginia to supply

less than half the number of patrol boats

as Maryland. Three months later, the Sun reported that

the equities were being resolved: negotiations had started with the court

clerks of St. Marys and Charles Counties to issue PRFC licenses, all funds

from Maryland were being deposited in a Maryland bank, and Virginia agreed

to expend more money to provide patrol boats.27

PRFC regulations and licenses were given judicial approval

by the Maryland Court of Appeals in Brown v. Bowles, 254 Md. 377, 254 A.2d

696 (1969). A 1929 Maryland statute had awarded Brown, as a riparian owner

of tidelands, the first right to stake out an area in front of his property.

Bowles, holding a haul seine license issued by PRFC, continually fished

in the area claimed by Brown, who brought a suit in equity to enjoin Bowles

from fishing there. Bowles argued that the 1929 statute, to which the Virginia

Legislature had not consented, was

-26-

not valid on the Potomac River. The Court accepted Bowles'

argument, but it placed greater reliance upon a public policy argument

that if Brown were to prevail, the PRFC's regulations would be severely

limited if its powers could be preempted by riparian owners.

IX. Environmental Problems

One use of the Potomac River where a great deal of interstate

controversy might be expected is relatively free of judicial activity and

other reported disputes. This use is in the area of water supply and waste

disposal. Perhaps the paucity of reported conflicts is due to the recent

emergence of pollution and water shortage as serious problems. In 1750

the flow of the Potomac provided as much pure water as anyone then could

imagine using. By 1863 soil pollution became a problem. But not until the

early 1900's did domestic sewage and industrial pollution become serious.28

Nevertheless, the volume of the flow was adequate, even if the quality

was poor. The environmental philosophy at that time did not seek prevention

of pollution at its source. The local jurisdictions that used the Potomac's

water provided their own filtration and treatment plants, without dissension

from others. 29

As the pollution problem became increasingly serious,

or at least more recognized, the states concerned formed an interstate

commission to deal with the problem. The Interstate Commission on the Potomac

River Basin (ICPRB) was created by a compact in 194030 upon

the urging of the Rivers and Harbors Committee of the Washington Board

of Trade. This Commission included members from Maryland, Virginia, West

Virginia, Pennsylvania, the District of Columbia, as

-27-

well as the President of the United States. The role of

the Commission was largely advisory and educational, with very limited

powers.

By 1965 the limitations of the ICPRB had become apparent.

Executives of the four states and the District met and created a Potomac

River Basin Advisory Committee to draft a framework for an organization

to provide planning, management, development, and utilization of the water

resources of the Potomac River. The Committee recommended that a Potomac

River Basin Commission supersede the ICPRB, with wider powers to deal with

abatement and control of water pollution, prevention of floods, promotion

of sound watershed management, supply of water for residential, agricultural,

and industrial needs, and management of riverside beauty and water-based

recreational needs. Maryland and Virginia adopted the compact, 31

but West Virginia and Pennsylvania rejected it. 32 Pennsylvania,

already a member of two interstate river compacts, wished to avoid undertaking

the increased personnel and financial obligations that supporting a more

powerful commission would entail. As it happened, increased federal involvement

with the affairs of the river has lessened the need for an encompassing

commission as proposed.

Maryland's jurisdiction over the Potomac River has given

the state control over the diversion of large quantities of water. In May,

1974, the Potomac Basin Reporter, a publication of the ICPRB, reported

that the Maryland Water Resources Administration had issued a permit to

Fairfax County to withdraw 15 mgd of Potomac water; the amount had been

reduced from an original 32 mgd request, after several Washington-area

jurisdictions had voiced objections.

-28-

Control of the Potomac's ecology requires more than control

over the river. Regulation of the entire surrounding watershed is necessary.

In September, 1973, the State of Virginia, which was joined by the Federal

EPA and the District of Columbia, filed suit in a United States district

court against the Washington Suburban Sanitary Commission (WSSC), on whose

behalf Maryland intervened. The WSSC operates the water supply and sewerage

systems in Montgomery and Prince Georges Counties, the two Maryland counties

which adjoin the District of Columbia. In 1970 the WSSC, the District,

and Virginia counties agreed to share the facilities of an expanded sewage

treatment plant at Blue Plains in the District. In the suit, Virginia charged

Maryland with exceeding her allotment of sewage flow to the exclusion of

other jurisdictions. Virginia sought a halt to all new sewer connections

in the Blue Plains service area of Maryland. Maryland's alleged indulgence

was especially irritating to Virginia in light of a restrictive sewer moratorium

that had been imposed in Fairfax County. The suit was settled by a "Blue

Plains Treaty", which was to be submitted as part of a consent decree.

The agreement33 designated an allocation of sewage flow and

sludge disposal.

In October of 1974 Maryland filed suit against the First

American Land Corporation and its development, Yogi Bear's Jellystone Park,

located in Falling Waters, West Virginia, in the Circuit Court of Washington

County. Maryland had thus sought to control a corporation outside its territory

and not doing business within Maryland, to enforce the state's environmental

control laws. The defendant (which had a construction permit from West

Virginia) was charged with

-29-

discharging inadequately treated sewage directly into

Maryland's Potomac. This action was settled by a consent decree in December,

1974.

X. Contemporary Disputes

Pollution is not the only environmental concern likely

to provoke disputes. The preservation of the natural beauty of the river

can usually be counted on to elicit differing views about any given proposal.

In 1961 Congress empowered the Secretary of the Interior (P.L. 87-362)

to acquire and administer certain lands in Prince Georges and Charles Counties,

Maryland,opposite Mount Vernon, in order to maintain the historic and scenic

values of the area. 34 The law was passed in response to a proposed sewage

disposal plant on the opposite shore in close proximity to Mount Vernon.

The Congressional action received wide support from civic and environmental

groups, but it was opposed by developers and several local landowners.

The composition of the factions on each side of a dispute, as usual, crossed

state lines. (Today, it seems that when one's interests are no longer closely

tied to his place of residence, the contestants in a dispute are more likely

to line up as "environmentalists versus developers" rather than Marylanders

versus Virginians.) The law (P.L. 87-362) was emasculated the following

year when Congress failed to provide funds for its implementation. 35

The propensity of citizens to align themselves according

to their economic interests rather than with their state of residence is

not new. During the late 1700's and early 1800's when the Potomac Canal

and the Chesapeake and Ohiu Canal were being discussed as a

-30-

major route to the western lands of the United States,

Maryland and Virginia cooperated in chartering the corporations to extend

the navigability of the Potomac River. Meanwhile, though, Baltimore merchants

feared losing their preeminent trading position to Georgetown or Alexandria.

They opposed much of the effort to obtain the state's support for the canal

projects. Maryland's Governor Thomas Johnson aligned himself with Virginia's

George Washington to persuade the Maryland Assembly to support projects

to open the upper Potomac to navigation.35a Baltimore's

support for the C&O Canal was obtained only after plans for a Maryland

Canal to connect Baltimore to the C&O36 had been approved.

When the Maryland Canal was deemed impracticable,

the Baltimore faction shifted its hopes to the fledgling

Baltimore &Ohio Railroad. Although the history of the chartering and

construction of the C&O Canal is full of difficulty and disputes, the

conflicts

were not of a nature that could be classified as interstate.

A number of twentieth century projects to develop the

Potomac for flood control, hydroelectric power, and water supply have been

proposed-each of which would involve the construction of dams. The U.S.

Army Corps of Engineers surveyed the Potomac River Basin in 1932, 1944,

and in 1956, and its recommendations have invariably included the erection

of several dams. Here, factions cross state lines and Maryland and Virginia

residents and landowners line up against the Corps of Engineers and the

contractors.

The Potomac River is becoming more and more subjected

to federal policy. The Department of the Interior has taken over parts

of the C&O Canal to be used as a national historical park. 37

The EPA is

-31-

increasingly active in regulating water pollution projects.

The Corps of Engineers is also increasing its regulation of the navigable

waterway.38 Such encroachments by the federal government

have made

Maryland fearful of losing its sovereignty and jurisdiction

over the river. When Maryland Senators J. Glenn Beall and Charles McC.

Mathias and Representative Gilbert Gude proposed creating a National Potomac

River Historical Area, Maryland's Secretary of Natural

Resources, James Coulter, voiced opposition to transferring further authority

to the federal government. 39

Twentieth century American life styles are changing problems

associated with the Potomac River. Use of the Potomac as a navigable highway

above tidewater is of limited importance. Recreational use of the river,

on the other hand, is increasing. Current disputes center around those

who want recreational development such as marinas and campsites, and those

who wish to enjoy the river in its natural wilderness state. The growth

of communities within the Potomac watershed has yielded greater use of

the river as a conduit for waste disposal. Reliance on the Potomac as a

source of drinking water emphasizes the potential overutilization of a

natural resource with a finite capacity. During certain summer droughts,

there is a meagre flow of water; at other times there are floods. Proposals

have been advanced for a series of dams that would solve both problems:

storing water for periods of drought, restraining during rainy seasons.

-32-

XI. The Future: Speculations

These problems are no less serious than those of the past

three hundred and fifty years, but their disposition will probably be somewhat

different. The existence of interstate compacts, the dominant role of the

federal government, and the propensity of factional interests to cross

state lines will likely serve to de-emphasize the problem as a conflict

between states.

Whether solutions on a regional basis will be forthcoming

remains, as always, to be seen.

-33-

FOOTNOTES

1. World Almanac and Book of Facts, New York (1976), p.

580.

2. VA. CODE ANN. ®7.1-7 (1950).

3. 2 Foundations of Colonial America 757 (New York, 1973);

emphasis added.

4. Maryland v. West Virginia, 217 U.S. 1, 28 (1910).

5. Frank W. Porter III, "Expanding the Domain: William

Gooch and the Northern Neck Boundary Dispute," The Maryland Historian V

(Spring, 1974).

6.. Wharton v. Wise, 153 U.S. 155, 162 (1894)

7. Id. at 163.

8. Barnes v. State, 186 Md. 287, 47 A.2d 50 (1946).

9. Walter S. Sanderlin, The Great National Project (Baltimore,

1946)

10. Max P. Allen, "William Pinkney's Public Career," Maryland

Historical Magazine 40 (1945), p. 227.

11. Maryland v. West Virginia, supra.

12. Mathews and Nelson, Report on the Location of the

Boundary Line along the Potomac River between Virginia and Maryland (Baltimore,

1928).

13. _Id. See VA. ACTS ch. 133 (1874) and MD. ACTS ch.

247 (1874). See also VA. ACTS ch. 246 (1877/78) and MD. ACTS ch. 374 (1878).

14. Id.

15. Burch's Digest, p. 213 (December 3, 1789). MD

Laws Ch. 46 (1788); MD. LAWS ch. 45 (1791).1 Stat. 1

16. Morris v. United States, v. Alexandria Canal

Co.,

17. 9 Stat. 35 (1846).

18. 59 Stat. 552 X101 (1945). MD. LAWS ch. 46 39 (1790).

174 U.S. 196 (1899). City of Georgetown 37 U.S. (12 Pet.) 91 (1838) .

19. Baltimore Sun, July 22, 1937.

20. This case is discussed in MD. L. REV. 268-81.

21. Edwin W. Beitzell, Life on the Potomac River (Washington,

1968).

22. Southern Maryland Times, September 27, 1946.

23. "The Oyster Wars," The Skipper (January 1959)

24. MD. LAWS ch. 765 (1957), and implementing legislation

MD. LAWS ch. 767, 770 (1957).

25. Different phases of this case are reported at 355

U.S. 269, 355 U.S. 880, and 371 U.S. 943 (1963). The last citation is the

approval of the report of the special master and the dismissal of the case

as moot.

26. MD. LAWS ch. 269, 736 (1959). VA. ACTS ch. 5, 28 (Ex.

Sess. 1959).

27. Baltimore Sun, March 11, 1964.

28. H. A. Kemp, "Solving Pollution Problems in the Potomac

River Basin," a speech published by the Interstate Commission on the Potomac

River Basin (Washington, 1950).

29. Id. p. 1. In 1905, the first river water filtration

plant for the District of Columbia was operational

.

30. MD. LAWS ch. 320 (1939) .

31. MD. LAWS ch. 30 (1971). VA. ACTS ch. 464 (1970).

32. Telephone conversation of April 21, 1976, with Anne

Blackburn

of the ICPRB.

33. Potomac Basin Reporter of June, 1974 (p. 4) and November,

1973 (p. 1) .

34. 75 Stat. 780 (1961).

35. Congressional Record, April 18, 1962, speech by the

Hon. Frances P. Bolton.

35A. E. S. Delaplaine, "The Life of Thomas Johnson," 15

Maryland Historical Magazine (1920), pp. 27-42.

36. Walter S. Sanderlin, "The Maryland Canal Project,"

Maryland Historical Magazine 41 (1946), pp. 51-65.

37. 16 U.S.C. 9410y (1971).

38. Washington Post editorial, March 21, 1976, p. B6.

39. Id.