The Dred Scott Decision

By Bob Moore, JNEM Historian

![]() ne

of the most important cases ever tried in the United States was heard in

St. Louis' Old Courthouse. The two trials of Dred Scott in 1847 and 1850

were the beginning of a complicated series of events which concluded with

a U.S. Supreme Court decision in 1857, and hastened the start of the Civil

War.

ne

of the most important cases ever tried in the United States was heard in

St. Louis' Old Courthouse. The two trials of Dred Scott in 1847 and 1850

were the beginning of a complicated series of events which concluded with

a U.S. Supreme Court decision in 1857, and hastened the start of the Civil

War.

![]() When

the first case began in 1847, Dred Scott was about 50 years old. He was

born in Virginia about 1799, and was the property, as his parents had been,

of the Peter Blow family. He had spent his entire life as a slave, and

was illiterate. Dred Scott moved to St. Louis with the Blows in 1830, but

was soon sold due to his master's financial problems. He was purchased

by Dr. John Emerson, a military surgeon stationed at Jefferson Barracks,

and accompanied him to posts in Illinois and the Wisconsin Territory, where

slavery had been prohibited by the Missouri Compromise of 1820. During

this period, Dred Scott married Harriet Robinson, also a slave, at Fort

Snelling; they later had two children, Eliza and Lizzie. John Emerson married

Irene Sanford during a brief stay in Louisiana. In 1842, the Scotts returned

with Dr. and Mrs. Emerson in St. Louis. John Emerson died the following

year, and it is believed that Mrs. Emerson hired out Dred Scott, Harriet,

and their children to work for other families.

When

the first case began in 1847, Dred Scott was about 50 years old. He was

born in Virginia about 1799, and was the property, as his parents had been,

of the Peter Blow family. He had spent his entire life as a slave, and

was illiterate. Dred Scott moved to St. Louis with the Blows in 1830, but

was soon sold due to his master's financial problems. He was purchased

by Dr. John Emerson, a military surgeon stationed at Jefferson Barracks,

and accompanied him to posts in Illinois and the Wisconsin Territory, where

slavery had been prohibited by the Missouri Compromise of 1820. During

this period, Dred Scott married Harriet Robinson, also a slave, at Fort

Snelling; they later had two children, Eliza and Lizzie. John Emerson married

Irene Sanford during a brief stay in Louisiana. In 1842, the Scotts returned

with Dr. and Mrs. Emerson in St. Louis. John Emerson died the following

year, and it is believed that Mrs. Emerson hired out Dred Scott, Harriet,

and their children to work for other families.

![]() On April 6th, 1846,

Dred Scott and his wife Harriet filed suit against Irene Emerson for their

freedom. For almost nine years, Scott had lived in free territories, yet

made no attempt to end his servitude. It is not known for sure why he chose

this particular time for the suit, although historians have considered

three possibilities: He may have been dissatisfied with being hired out;

Mrs. Emerson might have been planning to sell him; or he may have offered

to buy his own freedom and been refused. It is known that the suit was

not brought for political reasons. It is thought that friends in St. Louis

who opposed slavery had encouraged Scott to sue for his freedom on the

grounds that he had once lived in a free territory. In the past, Missouri

courts supported the doctrine of "once free, always free." Dred Scott could

not read or write and had no money. He needed help with his suit. John

Anderson, the Scott's minister, may have been influential in their decision

to sue, and the Blow family, Dred's original owners, backed him financially.

The support of such friends helped the Scotts through nearly eleven years

of complex and often disappointing litigation.

On April 6th, 1846,

Dred Scott and his wife Harriet filed suit against Irene Emerson for their

freedom. For almost nine years, Scott had lived in free territories, yet

made no attempt to end his servitude. It is not known for sure why he chose

this particular time for the suit, although historians have considered

three possibilities: He may have been dissatisfied with being hired out;

Mrs. Emerson might have been planning to sell him; or he may have offered

to buy his own freedom and been refused. It is known that the suit was

not brought for political reasons. It is thought that friends in St. Louis

who opposed slavery had encouraged Scott to sue for his freedom on the

grounds that he had once lived in a free territory. In the past, Missouri

courts supported the doctrine of "once free, always free." Dred Scott could

not read or write and had no money. He needed help with his suit. John

Anderson, the Scott's minister, may have been influential in their decision

to sue, and the Blow family, Dred's original owners, backed him financially.

The support of such friends helped the Scotts through nearly eleven years

of complex and often disappointing litigation.

![]() It is difficult

to understand today, but under the law in 1846 whether or not the Scotts

were entitled to their freedom was not as important as the consideration

of property rights. If slaves were indeed valuable property, like a car

or an expensive home today, could they be taken away from their owners

because of where the owner had taken them? In other words, if you drove

your car from Missouri to Illinois, and the State of Illinois said that

it was illegal to own a car in Illinois, could the authorities take the

car away from you when you returned to Missouri? These were the questions

being discussed in the Dred Scott case, with one major difference: your

car is not human, and cannot sue you. Although few whites considered the

human factor in Dred Scott's slave suit, today we acknowledge that it is

wrong to hold people against their will and force them to work as people

did in the days of slavery.

It is difficult

to understand today, but under the law in 1846 whether or not the Scotts

were entitled to their freedom was not as important as the consideration

of property rights. If slaves were indeed valuable property, like a car

or an expensive home today, could they be taken away from their owners

because of where the owner had taken them? In other words, if you drove

your car from Missouri to Illinois, and the State of Illinois said that

it was illegal to own a car in Illinois, could the authorities take the

car away from you when you returned to Missouri? These were the questions

being discussed in the Dred Scott case, with one major difference: your

car is not human, and cannot sue you. Although few whites considered the

human factor in Dred Scott's slave suit, today we acknowledge that it is

wrong to hold people against their will and force them to work as people

did in the days of slavery.

![]()

Hear

audio clips (RealAudio format) which feature a historical narrative from

Harriet Scott, who

talks about her struggle for freedom along with her husband, Dred.

Hear

audio clips (RealAudio format) which feature a historical narrative from

Harriet Scott, who

talks about her struggle for freedom along with her husband, Dred.

![]() RealAudio software to listen to the narratives can be downloaded

here.

RealAudio software to listen to the narratives can be downloaded

here.

![]() The Dred Scott

case was first brought to trial in 1847 in the first floor, west wing courtroom

of St. Louis' Courthouse. The Scotts lost the first trial because hearsay

evidence was presented, but they were granted the right by the judge to

a second trial. In the second trial, held in the same courtroom in 1850,

a jury heard the evidence and decided that Dred Scott and his family should

be free. Slaves were valuable property, and Mrs. Emerson did not want to

lose the Scotts,

The Dred Scott

case was first brought to trial in 1847 in the first floor, west wing courtroom

of St. Louis' Courthouse. The Scotts lost the first trial because hearsay

evidence was presented, but they were granted the right by the judge to

a second trial. In the second trial, held in the same courtroom in 1850,

a jury heard the evidence and decided that Dred Scott and his family should

be free. Slaves were valuable property, and Mrs. Emerson did not want to

lose the Scotts,  so

she appealed her case to the Missouri State Supreme Court, which in 1852

reversed the ruling made at the Old Courthouse, stating that "times now

are not as they were when the previous decisions on this subject were made."

The slavery issue was becoming more divisive nationwide, and provided the

court with political reasons to return Dred Scott to slavery. The court

was saying that Missouri law allowed slavery, and it would uphold the rights

of slave-owners in the state at all costs.

so

she appealed her case to the Missouri State Supreme Court, which in 1852

reversed the ruling made at the Old Courthouse, stating that "times now

are not as they were when the previous decisions on this subject were made."

The slavery issue was becoming more divisive nationwide, and provided the

court with political reasons to return Dred Scott to slavery. The court

was saying that Missouri law allowed slavery, and it would uphold the rights

of slave-owners in the state at all costs.

![]() Dred Scott was

not ready to give up in his fight for freedom for himself and his family,

however. With the help of a new team of lawyers who hated slavery, Dred

Scott filed suit in St. Louis Federal Court in 1854 against John F.A. Sanford,

Mrs. Emerson's brother and executor of the Emerson estate. Since Sanford

resided in New York, the case was taken to the Federal courts due to diversity

of residence. The suit was heard not in the Old Courthouse but in the Papin

Building, near the area where the north leg of the Gateway Arch stands

today. The case was decided in favor of Sanford, but Dred Scott appealed

to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Dred Scott was

not ready to give up in his fight for freedom for himself and his family,

however. With the help of a new team of lawyers who hated slavery, Dred

Scott filed suit in St. Louis Federal Court in 1854 against John F.A. Sanford,

Mrs. Emerson's brother and executor of the Emerson estate. Since Sanford

resided in New York, the case was taken to the Federal courts due to diversity

of residence. The suit was heard not in the Old Courthouse but in the Papin

Building, near the area where the north leg of the Gateway Arch stands

today. The case was decided in favor of Sanford, but Dred Scott appealed

to the U.S. Supreme Court.

![]() On March 6th, 1857,

Chief Justice Roger B. Taney delivered the majority opinion of the U.S.

Supreme Court in the Dred Scott case. Seven of the nine justices agreed

that Dred Scott should remain a slave, but Taney did not stop there. He

also ruled that as a slave, Dred Scott was not a citizen of the United

States, and therefore had no right to bring suit

On March 6th, 1857,

Chief Justice Roger B. Taney delivered the majority opinion of the U.S.

Supreme Court in the Dred Scott case. Seven of the nine justices agreed

that Dred Scott should remain a slave, but Taney did not stop there. He

also ruled that as a slave, Dred Scott was not a citizen of the United

States, and therefore had no right to bring suit  in

the federal courts on any matter. In addition, he declared that Scott had

never been free, due to the fact that slaves were personal property; thus

the Missouri Compromise of 1820 was unconstitutional, and the Federal Government

had no right to prohibit slavery in the new territories. The court appeared

to be sanctioning slavery under the terms of the Constitution itself, and

saying that slavery could not be outlawed or restricted within the United

States. The American public reacted very strongly to the Dred Scott Decision.

Antislavery groups feared that slavery would spread unchecked. The new

Republican Party, founded in 1854 to prohibit the spread of slavery, renewed

their fight to gain control of the Congress and the courts. Their well-planned

political campaign of 1860, coupled with divisive issues which split the

Democratic Party, led to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of

the United States and South Carolina's secession from the Union. The Dred

Scott Decision moved the country to the brink of Civil War.

in

the federal courts on any matter. In addition, he declared that Scott had

never been free, due to the fact that slaves were personal property; thus

the Missouri Compromise of 1820 was unconstitutional, and the Federal Government

had no right to prohibit slavery in the new territories. The court appeared

to be sanctioning slavery under the terms of the Constitution itself, and

saying that slavery could not be outlawed or restricted within the United

States. The American public reacted very strongly to the Dred Scott Decision.

Antislavery groups feared that slavery would spread unchecked. The new

Republican Party, founded in 1854 to prohibit the spread of slavery, renewed

their fight to gain control of the Congress and the courts. Their well-planned

political campaign of 1860, coupled with divisive issues which split the

Democratic Party, led to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of

the United States and South Carolina's secession from the Union. The Dred

Scott Decision moved the country to the brink of Civil War.

![]() Ironically, Irene

Emerson was remarried in 1850 to Calvin C. Chaffee, a northern congressman

opposed to slavery. After the Supreme Court decision, Mrs. Chaffee turned

Dred and Harriet Scott and their two daughters over to Dred's old friends,

the Blows, who gave the Scotts their freedom in May 1857. On September

17, 1858, Dred Scott died of tuberculosis and was buried in St. Louis.

His grave was moved in the 1860s to Calvary Cemetery in northern St. Louis,

and marked due to the efforts of the Rev. Edward Dowling in 1957. Dred

Scott did not live to see the fratricidal war touched off at Fort Sumter

in 1861, but did live to gain his freedom. The ultimate result of the war,

the end of slavery throughout the United States, was not something Dred

Scott could have foreseen in 1846, when he decided to sue for his freedom

in St. Louis' Old Courthouse.

Ironically, Irene

Emerson was remarried in 1850 to Calvin C. Chaffee, a northern congressman

opposed to slavery. After the Supreme Court decision, Mrs. Chaffee turned

Dred and Harriet Scott and their two daughters over to Dred's old friends,

the Blows, who gave the Scotts their freedom in May 1857. On September

17, 1858, Dred Scott died of tuberculosis and was buried in St. Louis.

His grave was moved in the 1860s to Calvary Cemetery in northern St. Louis,

and marked due to the efforts of the Rev. Edward Dowling in 1957. Dred

Scott did not live to see the fratricidal war touched off at Fort Sumter

in 1861, but did live to gain his freedom. The ultimate result of the war,

the end of slavery throughout the United States, was not something Dred

Scott could have foreseen in 1846, when he decided to sue for his freedom

in St. Louis' Old Courthouse.

![]()

Background: Slavery in Missouri

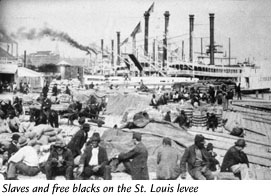

![]() Slavery

in Missouri was different from slavery in the deep south. The majority

of Missouri's slaves worked as field hands on farms along the fertile valleys

of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. St. Louis, the largest city in

the state, maintained a fairly small African-American population throughout

the early part of the nineteenth century. Life in the cities was different

for African-Americans than life on a rural plantation. The opportunities

for interaction with whites and free blacks were constant, as were those

for greater freedom within their slave status. Because slavery was unprofitable

in cities such as St. Louis, African-Americans were often hired out to

others without a transfer of ownership. In fact, many masters illegally

allowed their slaves to hire themselves out and find their own lodgings.

This unusual state of affairs taught African-Americans to fend for themselves,

to market their abilities wisely, and to be thrifty with their money.

Slavery

in Missouri was different from slavery in the deep south. The majority

of Missouri's slaves worked as field hands on farms along the fertile valleys

of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. St. Louis, the largest city in

the state, maintained a fairly small African-American population throughout

the early part of the nineteenth century. Life in the cities was different

for African-Americans than life on a rural plantation. The opportunities

for interaction with whites and free blacks were constant, as were those

for greater freedom within their slave status. Because slavery was unprofitable

in cities such as St. Louis, African-Americans were often hired out to

others without a transfer of ownership. In fact, many masters illegally

allowed their slaves to hire themselves out and find their own lodgings.

This unusual state of affairs taught African-Americans to fend for themselves,

to market their abilities wisely, and to be thrifty with their money.

![]() Slavery was not

a "Southern" problem alone. Many northern states phased out slavery as

late as the 1830s, and states such as Delaware and New Jersey still had

slave-owning residents as late as 1860. On a local level, residents of

Illinois owned slaves (under long-term indenture agreements of 40 years

or longer) during the period of the Dred Scott trials, and a special provision

in the Illinois constitution allowed slaves to work in the salt mines across

the Mississippi from St. Louis as long as they were not held there for

over one year at a stretch. Many people in southern Illinois supported

slavery. No slaves in the St. Louis area picked cotton however, and few

worked in farm fields. Most worked as stevedores and draymen on the riverfront,

on riverboats, in the lead and salt mines, as handymen, janitors and porters

(like Dred Scott), and as maids, nannies, and laundresses (like Harriet

Scott).

Slavery was not

a "Southern" problem alone. Many northern states phased out slavery as

late as the 1830s, and states such as Delaware and New Jersey still had

slave-owning residents as late as 1860. On a local level, residents of

Illinois owned slaves (under long-term indenture agreements of 40 years

or longer) during the period of the Dred Scott trials, and a special provision

in the Illinois constitution allowed slaves to work in the salt mines across

the Mississippi from St. Louis as long as they were not held there for

over one year at a stretch. Many people in southern Illinois supported

slavery. No slaves in the St. Louis area picked cotton however, and few

worked in farm fields. Most worked as stevedores and draymen on the riverfront,

on riverboats, in the lead and salt mines, as handymen, janitors and porters

(like Dred Scott), and as maids, nannies, and laundresses (like Harriet

Scott).

![]()

Additional Information

![]() In addition to

slaves, St. Louis also had a fairly large free black community. African-Americans

in St. Louis were able to live within the strict "black codes", which were

harsh laws that applied to all African-Americans, both free and slave.

Many free blacks owned businesses which carted goods from place to place

after they

In addition to

slaves, St. Louis also had a fairly large free black community. African-Americans

in St. Louis were able to live within the strict "black codes", which were

harsh laws that applied to all African-Americans, both free and slave.

Many free blacks owned businesses which carted goods from place to place

after they  were off-loaded from river boats. Real estate was also a

business known to free blacks. Others owned large barber emporiums, some

with real gold faucets, marble countertops and crystal chandeliers, which

were used by all the important white men of the town. These barbers were

able to gather information that their white customers discussed and pass

it along to the black community. Many became so rich that they became known

as the "Colored Aristocracy" of St. Louis.

were off-loaded from river boats. Real estate was also a

business known to free blacks. Others owned large barber emporiums, some

with real gold faucets, marble countertops and crystal chandeliers, which

were used by all the important white men of the town. These barbers were

able to gather information that their white customers discussed and pass

it along to the black community. Many became so rich that they became known

as the "Colored Aristocracy" of St. Louis.

![]() By 1835 an African-American

church had started in St. Louis; Sundays were also days of rest for the

slaves, when gossip and news could be passed from one African-American

to another, in or out of church. African-Americans who were literate would

read newspapers aloud to others at night or on Sunday. These circumstances

made urban slavery unusual. An African-American could acquire accurate

information about nearly any subject, including how to sue for one's freedom.

By 1835 an African-American

church had started in St. Louis; Sundays were also days of rest for the

slaves, when gossip and news could be passed from one African-American

to another, in or out of church. African-Americans who were literate would

read newspapers aloud to others at night or on Sunday. These circumstances

made urban slavery unusual. An African-American could acquire accurate

information about nearly any subject, including how to sue for one's freedom.

![]() Because slavery

in St. Louis became less and less profitable as years went by, masters

hired out their slaves, usually for periods of a year at a time. This meant

that slaves encountered a certain amount of uncertainty regarding whom

they would be working for from year to year. Often, slaves, were able to

save a cut of their wages for themselves. This meant that after years of

saving, they might be able to purchase their own freedom. Several St. Louis

slaves did just that, although it was expensive; an average healthy male

slave sold for about $500 in 1850, roughly $14,000 in today's money. In

several cases, a father would purchase his freedom, set up a business,

and save enough money to purchase his wife and children from their masters;

he could then set them free legally.

Because slavery

in St. Louis became less and less profitable as years went by, masters

hired out their slaves, usually for periods of a year at a time. This meant

that slaves encountered a certain amount of uncertainty regarding whom

they would be working for from year to year. Often, slaves, were able to

save a cut of their wages for themselves. This meant that after years of

saving, they might be able to purchase their own freedom. Several St. Louis

slaves did just that, although it was expensive; an average healthy male

slave sold for about $500 in 1850, roughly $14,000 in today's money. In

several cases, a father would purchase his freedom, set up a business,

and save enough money to purchase his wife and children from their masters;

he could then set them free legally.

![]() Missouri slave-holders

were worried about the rise in the population of free blacks. Many whites

provoked incidents meant to strike fear into the hearts of free blacks,

or to get them to leave Missouri. It was generally believed by slave-holders

that free blacks stirred up discontent among the slaves, and caused them

to run away, slow down their work, or sue for their freedom if they were

eligible.

Missouri slave-holders

were worried about the rise in the population of free blacks. Many whites

provoked incidents meant to strike fear into the hearts of free blacks,

or to get them to leave Missouri. It was generally believed by slave-holders

that free blacks stirred up discontent among the slaves, and caused them

to run away, slow down their work, or sue for their freedom if they were

eligible.

![]()

The Dred Scott Courtroom in St. Louis' Old Courthouse

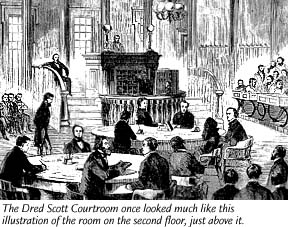

![]() The

courtroom where the Dred Scott cases were heard is no longer in existence.

In 1855, even before the Scotts' campaign for their freedom ended,

the courtroom received extensive renovation. The large courtroom, as originally

constructed, occupied the entire west wing. An architectural flaw was discovered

which threatened the wing's ceiling on the first floor, and additional

support was required. As a result, a new corridor running on an east-west

axis was added, dividing the large courtroom where the Scott trials were

heard into two smaller courtrooms. A display about the trial is exhibited

in this corridor, near the original site.

The

courtroom where the Dred Scott cases were heard is no longer in existence.

In 1855, even before the Scotts' campaign for their freedom ended,

the courtroom received extensive renovation. The large courtroom, as originally

constructed, occupied the entire west wing. An architectural flaw was discovered

which threatened the wing's ceiling on the first floor, and additional

support was required. As a result, a new corridor running on an east-west

axis was added, dividing the large courtroom where the Scott trials were

heard into two smaller courtrooms. A display about the trial is exhibited

in this corridor, near the original site.

![]()

Park Info | Arch

History & Architecture | Museum

Tour | Top of the Arch

| Old Courthouse

St. Louis History

| Films | Educator's

Guide | Library/Archives

| Volunteer! | Credits

What's New | Lewis & Clark | Special Events | Permanent Exhibits | National Park Service | St. Louis Info. | News Releases | Traveling Exhibits

![]()