The Forgotten Mothers of Maryland

by Edward C. Papenfuse, State Archivist & Commissioner

of Land Patents

Georges de la Tour, ca. 1640. The Repentant Magdalen,

National Gallery of Art

Writing history is an exercise of contemplation and imagination, of

projecting back in time in an effort to understand why and how people behaved,

how they viewed the world about them, and what the major influences were

that affected their daily lives. Here a repentant Magdalen reflects on

what? Her past sins? Whether or not there is true forgiveness? Is it merely

an artist's study in artificial light, so much the rage when it was painted?

Is it the skull that attracts us or the delicate slender fingers that rest

lightly upon it? Or is it her eyes which seem far from repentant, lending

a sense of great concentration, resigned wisdom, and the presence of a

powerful, yet constrained, intellect that could equal and perhaps better

that of any man?

To what degree do we see in the remnants of the past, whether they be

art, archival, or archaelogical, our own reflections, our own desires to

undertand ourselves and to make sense of the world about us? How much in

our efforts to know the past are we constrained by what we think we know

of the present? How do we know what we know and what does it mean?

It is both the challenge and the reward of studying history to see the

past in a new light, to touch delicately whatever evidence there is, and

to transform it into a compelling, carefully crafted and documented narrative

of what we think we have found..

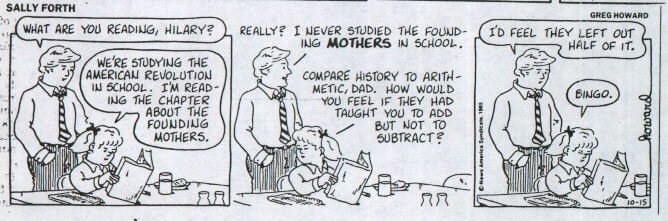

Often cartoonists in a single strip of quickly sketched frames capture

more meaning than any number of scholarly monographs. Take for example

this Sally Forth published in the Baltimore Sun for October 15,

1985.

Ted: "What are you reading, Hilary?"

Hilary: "We're studying the American Revolution in School. I'm reading

the chapter about the founding mothers."

Ted: "Really? I never studied the founding Mothers in school."

Hilary: "Compare history to arithmetic, dad. How would you feel if they

had taught you to add but not to substract?"

Ted: "I'd feel they left out half of it."

Hilary: "Bingo."

In an address to the Foxcroft School in Middleburg, Virginia in 1975, the

noted historian of Revolutionary America, Edmund S. Morgan, suggested that

the best way to celebrate the achievements of the Founding Fathers would

be to persistently re-examine what we believe those achievements to be,

re-evaluating the surviving evidence carefully and with a fresh mind. "The

challenge of their history is not to restore the past, but," Morgan told

his audience, "to enliven the imagination, to look at the unwarranted assumptions

of our own time and then have the nerve to say once more, 'It ain't necessarily

so.'" [12-165]

This evening it is my goal to enliven your imagination and challenge

some unwarranted assumptions about the role of three women named Anne in

the history of Maryland.

The first Anne (Anne Mynne) was once well known, but in the years following

her death in 1622 her contributions were confused with those of her mother-in-law,

and then forgotten altogether.

The maiden name of the second Anne (Anne Arundel) who died in 1649,

is mispronounced almost every day in the news. For those who live in the

Annapolis area it also graces a section of the regional edition of the

Baltimore SUN, yet her importance to the formative years of the first Catholic

colony in English America goes largely unnoticed.

The third Anne (Anne Wolseley) who died in 1679 or 1680, simply has

been ignored. Her remains were found not too long ago, buried in a lead

coffin in the midst of a St. Mary's County corn field.

To understand the role all three played in the founding of Maryland,

and to help set the record straight we begin not with the settlement of

Maryland in 1634, but nearly 1460 years earlier with yet another woman,

St. Cecilia. St. Cecilia is perhaps best known from a painting, and from

her life's story as told by the founder of Modern English Literature, Geoffey

Chaucer. [12-177]

In 1515 the Italian Renaissance artist Raphael painted a magnificent

portrait of St. Cecilia for an alterpiece which now hangs in a museum in

Bologna, Italy. [the Pinacotes Nazionale, Bologna...,].

Raphael's painting, see 12-177 for documentation; from

Indagini per un dipinto La Santa Cecilia di Raffaello, Bologna:

Edizioni ALFA, 1983, including an article by Thomas H. Connoly, "The cult

and iconography of St. Cecilia before Raphael, pp. 121-139

Note the inspiring beauty of St. Cecilia, patron saint of music and

the blind; note how richly dressed she is and how her head turns towards

"the heavenly choir in the clouds. On the left are St. Paul and

St. John the Evangelist, on the right St. Augustine and St. Mary Magdalene,

all of whom are closely associated with heavenly visions. At their feet,

battered and broken, lie assorted musical instruments. Even the pipes of

the [small] organ [St. Cecilia holds in her right hand] are beginning to

slip. .... an allegory of the Christian concept of music demonstrating

'the inferiority of all music perceived by the senses to what is absolute

music in its religious sense,.... [music] which can be played only by angels

and can be heard only by saints'. [12-177]

The Second Nun's Tale of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales is

about the life of St. Ceciliae who was martyred in Sicily under Roman Emperor

Marcus Aurelius (c.176 a.d.). It was written sometime between 1387 and

Chaucer's death in 1400.

Chaucer begins by explaining the signficance of Cecilia's name:

First let me tell you whence her name has sprung,

Cecilia, meaning, as the books agree,

'Lily of Heaven' in our English tongue,

To signify her chase virginity;

Or for the whiteness of her constancy,

The greeness of her conscience, of her fame

The scent and sweetness, 'lily' was her name.

Cecilia may betoken 'path to the blind'

From the example given in her story;

Or in Cecilia some would have us find

A union as it were of 'Heaven's glory' ...

Cecilia may be also said to mean

'Wanting in blindness,' as she had the light

Of sapience and bearing calm and clean; ...

And just as one may look to heaven and see

The sun and moon, and where the stars are hung,

so in this maiden, spiritually,

We see her faith and magnanimity

And the whole clarity of her wisdom thence

In many works of shining excellence.

[quote from pp. 452-453 4-2744]

Chaucer also reminds his readers that when confronted with the threats

of her enemy, Almacius, the Emperor's official, Cecilia replied:

Your power is little to be feared indeed;

Power of mortal man is soon discerned

to be a bladder full of wind and spurned;

for prick it with a needle when it's blown

and the inflated boast is overthrown.'

To the end, even when half dead with 'carven neck' from the blows of her

assasin's knife,

Cecilia never

ceased in teaching.

The faith she fostered,

and continued preaching.

In time, Raphael's saintly St. Cecilia became less so as images of her

'proliferated throughout' the 16th and 17th centuries. About 1610 the Florentine

painter, Orazio Gentileschi portrayed her as a simply dressed young woman

playing the organ for an angel:

Orazio Gentileschi, c. 1610, Florence, St. Cecilia and

an Angel, National Gallery of Art, 12-241

Strozzi, St. Cecilia, ca. 1618-1620

By the time of Anne Mynne Calvert's death in 1622, Bernardo Strozzi,

the master painter of Genoa had depicted her as a quite sensuous, richly

dressed, young woman

"with an organ (barely visible pipes, left, rear) - which she is tradtionally

credited with having invented- a violin (mid-left), and a lute (center,

right)." [Walter's Catalogue, p. 26]

But what does all this about St. Cecilia have to do with the three forgotten

Annes of Maryland? For that answer we need to look more closely at the

evidence pertaining to all three.

Anne Mynne Calvert

We probably will never know for certain why George Calvert (1578/1579-1632)

and Anne Mynne chose to honor St. Cecilia by being married on her feast

day, November 22, 1604, at St. Peter's Church, Cornhill in London. Perhaps

it was to pay tribute to both the Saint and to honor George Calvert's wealthy

patron and political benefactor, Robert Cecil.

Robert Cecil (1563?-1612) was the 1st Earl of Salisbury and Chief Minister

to King James I.

He lived at Hatfield House which he built between 1607 and 1611 and

where the Cecil family still resides today. It is not far from where Anne

Mynne lived, but what connection she or her family may have had with the

Cecil's is not known. What we do know is that Anne Mynne was a devout Roman

Catholic, the granddaughter of a minor court official in the reign of Henry

the VIII, the daughter of a wealthy Hertfordshire gentleman, who, with

her husband, and her first born, paid homage to St. Cecilia in a number

of ways significant to the history of Maryland.

George Calvert grew up in Yorkshire where he built a country home, Kiplin

Hall, for himself, Anne, and their rapidly growing family.

(12-240)

Between 1605 and 1622 Anne bore eleven children, dying in childbirth

with the last. A contemporary recorded the event: "On Thursday [August

8] Secretary Calvert's lady went away in childbirth, leaving many little

ones behind her. She had not been sick above two days." [14-327-8-24]

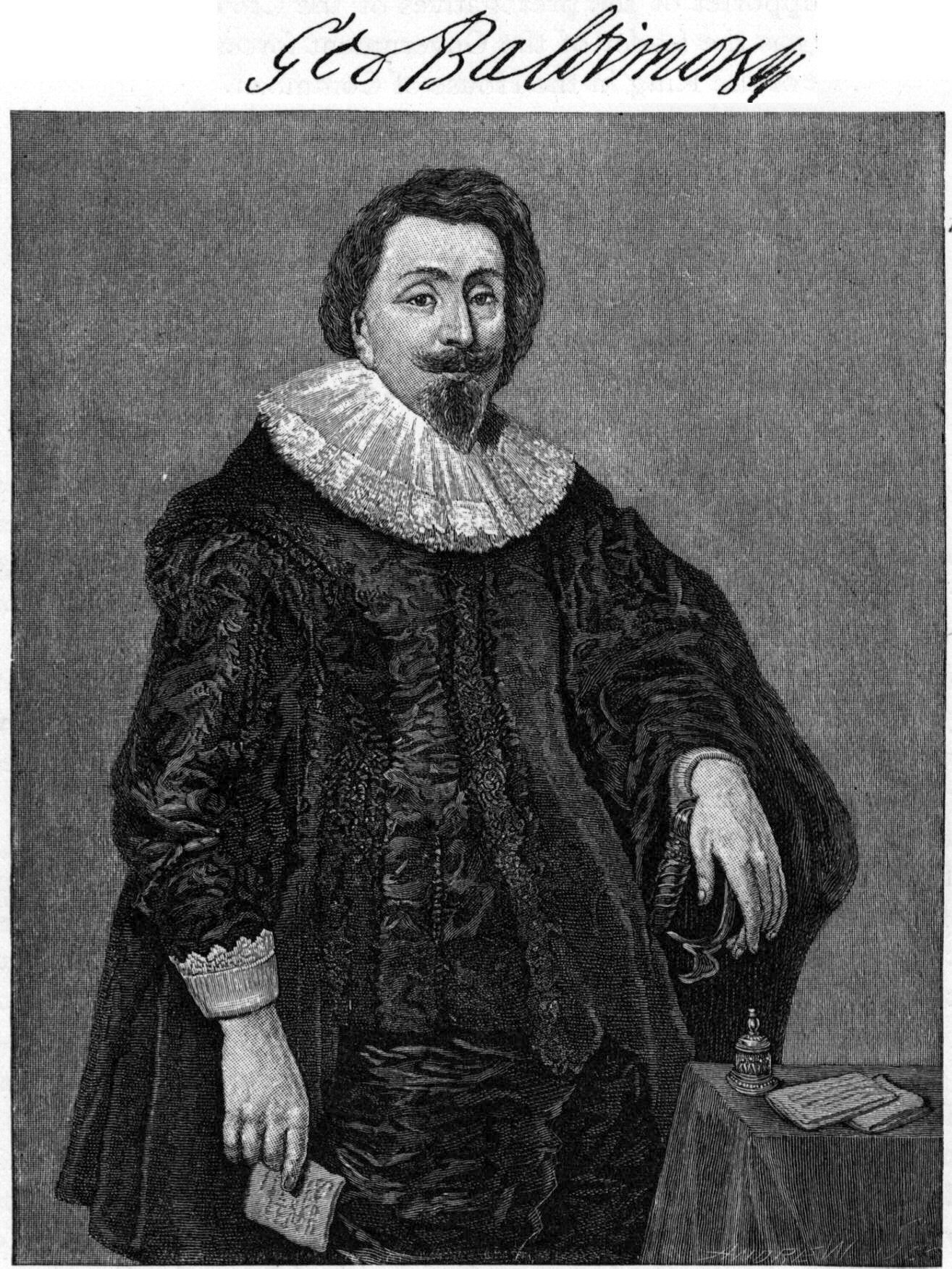

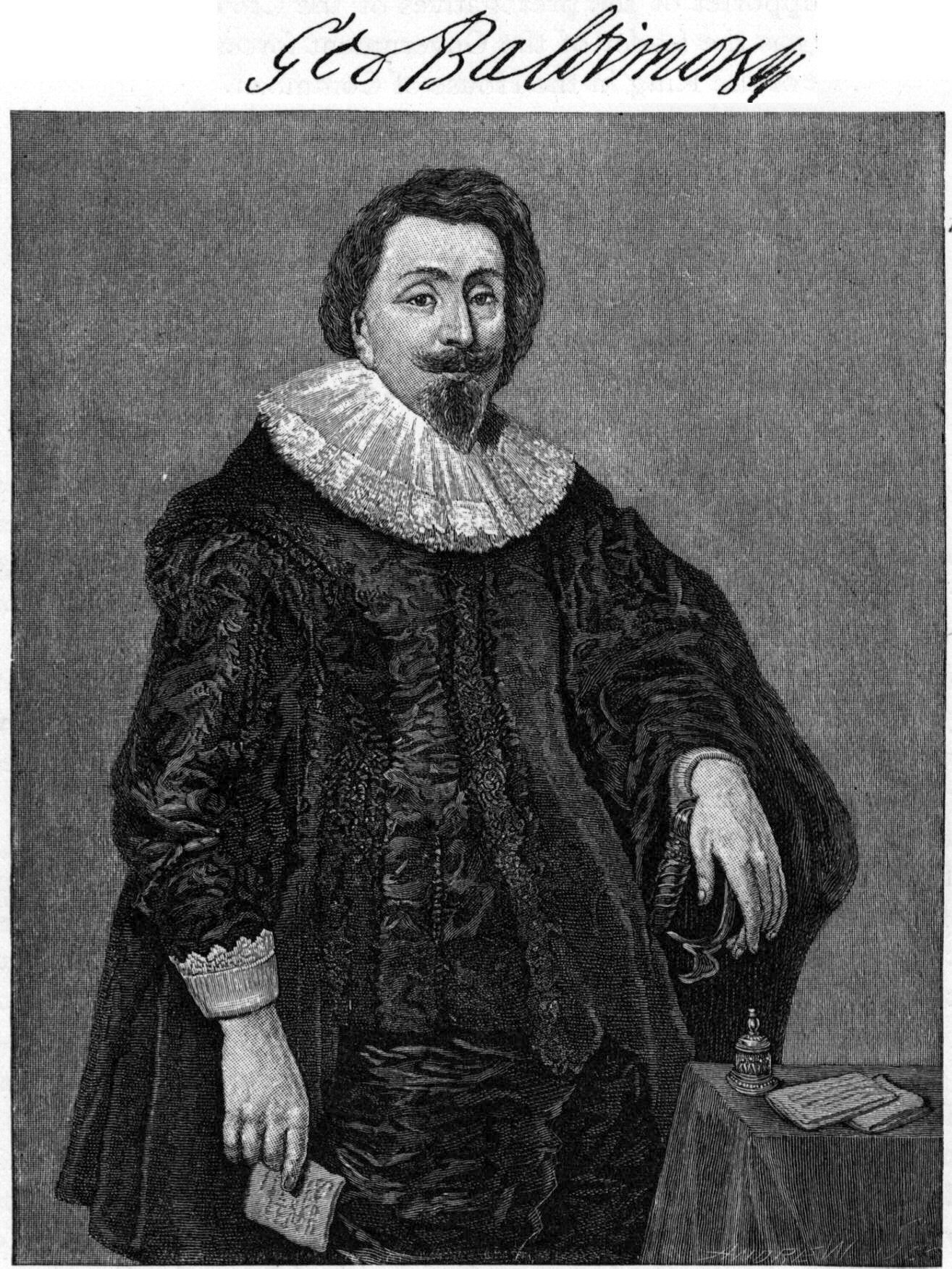

George Calvert from Justin Winsor's Narrative andCritical

History, III

George Calvert was called 'Secretary' because in 1619 King James I

appointed him Secretary of State, the equivalent of a Foreign Minister.

His predecessor in the office, Sir Thomas Lake, had been dismissed because

of his wife's indiscressions. The King wanted to be certain that Calvert

did not have the same problem with Lady Calvert. Before making up his mind

about the pending appointment, he questioned Calvert carefully on many

subjects, including pointed inquiries about the reliability of his wife.

"She is a good woman," Calvert replied, "and has brought me ten children;

and I can assure your majesty, she is not a wife with a witness," a response

which historians construe to mean that "Lady Calvert was by no means a

second Lady Lake" who "would betray what was confided to her." It also

seems that the King had had enough of "head strong, high spirited wives"

like Lady Lake of whom he had experienced "much wilfulness and [a] violent

temper." [14-327-8, p. 10-11; 12-62]

George Calvert got the appointment, only to lose Lady Anne three years

later. She died giving birth in London where her husband was immersed in

efforts to secure a Spanish bride for Prince Charles. Her body was taken

to her family's parish church, St. Mary's Hertingfordbury, in Hertfordshire,

about nineteen miles north of London.

St. Mary's, sign, 12-143-1

St. Mary's church, 12-143-2

George was overcome by grief. He wrote the Marquis of Salisbury thanking

him for his words of comfort:

I am much bound to you for the sense you have of my sufferings,

and for the wise advice you give me to bear it patiently. I shall strive

to do it, but there are so many images of sorrow that represent themselves

every moment to me in her loss, who was the dear companion and only comfort

of my life, as I doubt I shall not so easily forget it as a wise man should;

for which God forgive me if I offend, who for my sins only has laid this

heavy cross upon me, and yet far lighter than I deserve, though to my weak

heart it be almost insupportable." [12-45-1, Krugler]

Anne Mynne's Tomb, St. Mary's church, 12-143-3

As a memorial George Calvert built Anne Mynne a splendid Italianate

tomb placing his recumbant wife in marble before a mantel adorned with

the Calvert shield on the Left,

Anne Mynne's Tomb, St. Mary's church, detail of Mynne

shield12-143-5

the Mynne Coat of Arms on the right,

Anne Mynne's Tomb, St. Mary's church, detail of two family

shields encorporated into one in the middle, 12-143-6

and the two coats of arms elevated and joined in the middle.

In the language of heraldry there were

"three shields of Arms. On the centre shield: Paly of six, or[gold]

and sable [silver], a Bend counterchanged for Calvert; impaling, Sable[silver];

a Fess dancette paly of four, gules and ermine, beween six-crosslet argent[silver],

for Mynne. On the other, Calvert and Mynne emblazoned alone."[12-144].

George Calvert sought solace in the household of the Catholic Earl of

Arundel where a high mass had been held in memory of his wife Anne and

where she seemed to have spent much of her time while in London. [Krugler]

It was this same Earl of Arundel who may have been a student and

patron of the noted poet and compiler of the first Italian-English dictionary,

John Florio (1533-1625). Indeed, both Florio and George Calvert had their

portraits painted by the same artist, Daniel Mytens the elder at about

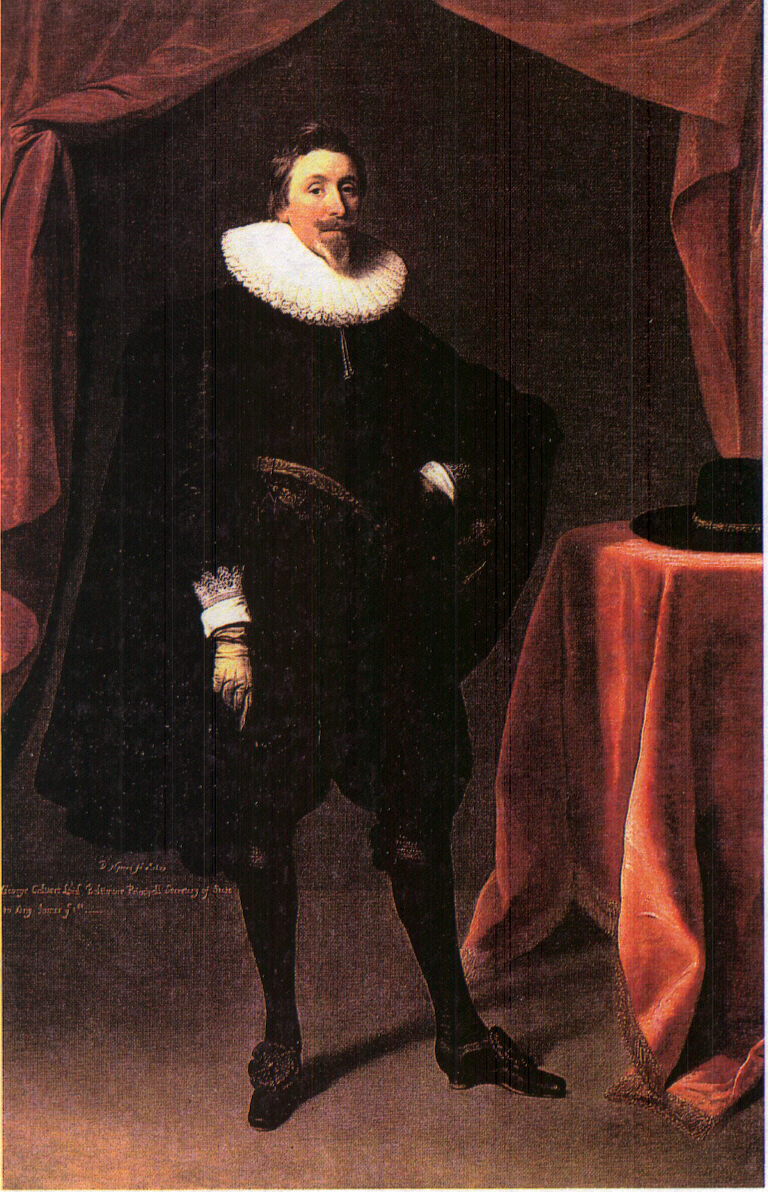

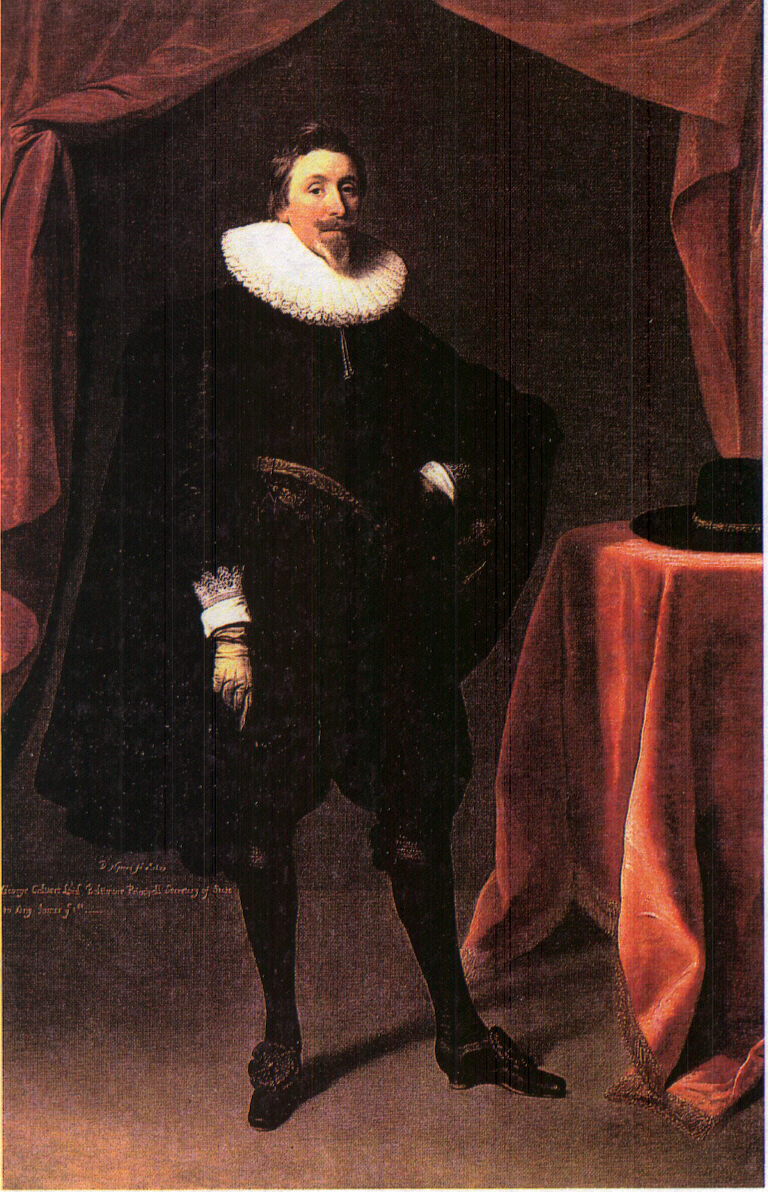

the same time. [12-175]

George Calvert by Daniel Mytens

Historians will probably never be able to discover how George Calvert

felt about the work of John Florio who spent his life attempting to make

English and Italian gender neutral. Florio particularly disliked the common

translation of Fatti Maschii Parole Femine (today the controversial

unofficial Motto of the State of Maryland) which men like Sir Thomas Bodley,

who founded the Bodleian library at Oxford, used disparagingly to mean

"wordes are women and deeds are men." Instead Florio argued in his preface

to A WORLD OF WORDES (1598) that those words should be interpreted

differently, without reference to gender. Florio explained:

As our Italians say, Le Parole sono femine, & i fatti sono maschii,

words they are women, and deeds they are men. But let such know that detti

and fattii, words and deeds with me are all of one gender, and though they

were commonly feminine, why might not I, by strong imagination ... alter

their sex?

It is not difficult to imagine that Florio found a sympathetic ear in Anne

Mynne Calvert and it is plausible to argue that George Calvert may have

chosen to honor the memory of both his wife (who died in 1622) and John

Florio (who died in 1625) by adopting as his family motto Fatti Maschii

Parole Femine which from Florio's perspective translates gentle

words, strong deeds. Written in latin on the margin of a 1622 description

of his coat of arms, it is first found in use on a wax seal affixed to

George Calvert's last surviving letter of March 28, 1632 and is now boldly

emblazoned on the Great Seal of Maryland which is affixed to all laws and

most official pronouncements of the state.

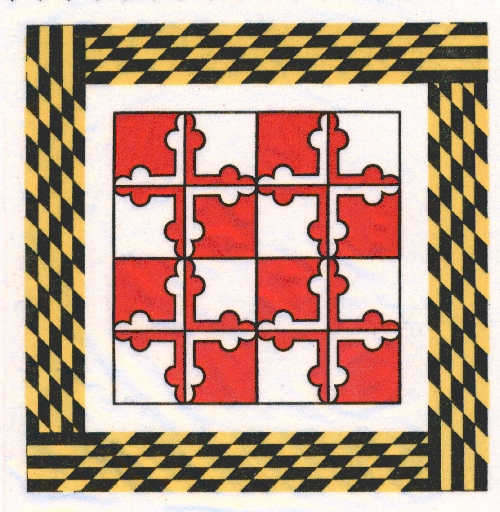

So important was the memory of his wife Anne Mynne that when George

Calvert was elevated to the Irish Peerage as Baron Baltimore in 1625, I

believe he chose to pay tribute not only to his Crossland origins, but

also to his wife's family who had the same colors and a buttoned cross

in their coat of arms, although in heraldic terms only the Crossland's

were entitled to countercharging their colors of red and white as it appears

Maryland's Great Seal and flag. [12-145].

Time has dimmed the memory of Anne Mynne, just as her tomb has been

moved from a place of honor near the alter to a dark corner in the rear

of St. Mary's Church.

Subsequent generations of scholars and the annotated code of Maryland

have mistaken the Cross that appears on the Calvert Coat of Arms, the Great

Seal of Maryland, the State Flag, and by law on every flag pole where the

State Flag is flown, as exclusively the Cross Botany of the Crossland family

to which George Calvert's mother may or may not have belonged. Perhaps

it is time to give Anne Mynne her due. Not only does she deserve credit

for at least half of the most visible symbols representing Maryland, but

she also provided material wealth and inspiration for her husband who renounced

the political wold, openly joined the Catholic church, and who may have

been far less sexist than contemporaries and historians may have imagined.

Cecil Calvert's portrait, by Gerard Soest, Enoch Pratt

Free Library

If subsequent generations of Calvert family historians forgot her,

Anne Mynne's first born did not. Doubly Christened in 1605 after his father's

earthly patron, Sir Robert Cecil, and after the Saint who used words and

deeds to preach and to educate, even on her death bed, Cecilius Calvert

was the first to publish the family coat of arms and spent the better part

of his adult life teaching about, writing about , and promoting the virtues

of emigrating to the shores of the upper Chesapeake Bay.

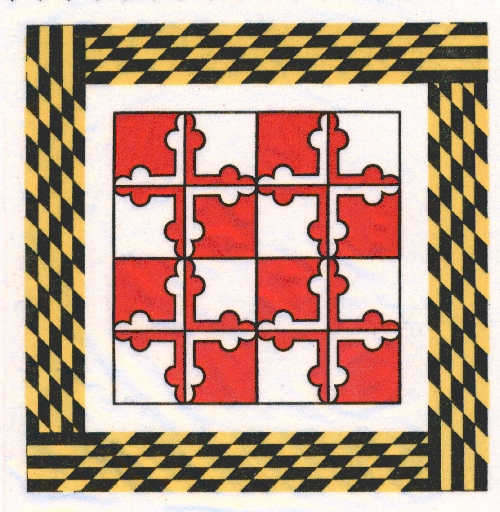

Calvert Coat of Arms

Cecil Calvert first used his mother's armorial bearings on the first

map of Maryland published in 1635 and again on this second edition of 1671.

The map was an integral part of the promotional literature for his new

colony granted by King Charles I in 1632 and called Maryland after the

Queen, Henrietta Maria.

Maryland Manual cover with the Ark & Dove,

2-45-1991

It was to this 'fruitful and delightsome land' of Maryland that Cecil

Calvert dispatched the Ark and the Dove in the fall of 1633 laden with

supplies and 'neere' 200 prospective settlers. Surely it was not a coincidence

that, as Father White, one of the passengers relates:

on Friday, the 22. of November, 1633, [St. Cecilia's day] a small

gale of winde comming gently from the Northwest, they weighed from the

Cowes in the Isle of Wight about ten in the morning ...

map of Maryland, 1671; first to show counties

By 1671 the Colony was flourishing. This map, revised from the first

edition of 1635 with two rows of trees added to the north in the hopes

of protecting the colony from encroachment, was published with a condensed

history of the colony extolling the virtues of religious freedom for all

who would settle there. Graphically it documented the progress of the colony

since its beginnings in 1634. In addition to the wonderfully colored and

enlarged coat of arms proudly bearing the quartering of the Mynne and Calvert

shields, it displayed the names of all the local administrative districts

still called counties after their English counterparts.

Anne Arundel Calvert

One of the counties most prominent on the map and among the first to

be erected in Maryland (after St. Mary's) was Anne Arundel. Created by

act of assembly in April 1650, it was named for the late Anne Arundell,

wife of Cecil Calvert, who had died the previous July at the age of 34.

[12-93, Niclin; Hastings]. Anne Arundel was the daughter

of Thomas Arundell of Wardour castle in Wiltshire. She was married to Cecil

Calvert in 1628. They had four children of their own, and by the will of

George Calvert, the first Lord Baltimore, they were enstrusted with the

care of Cecil's half-brother, Philip.

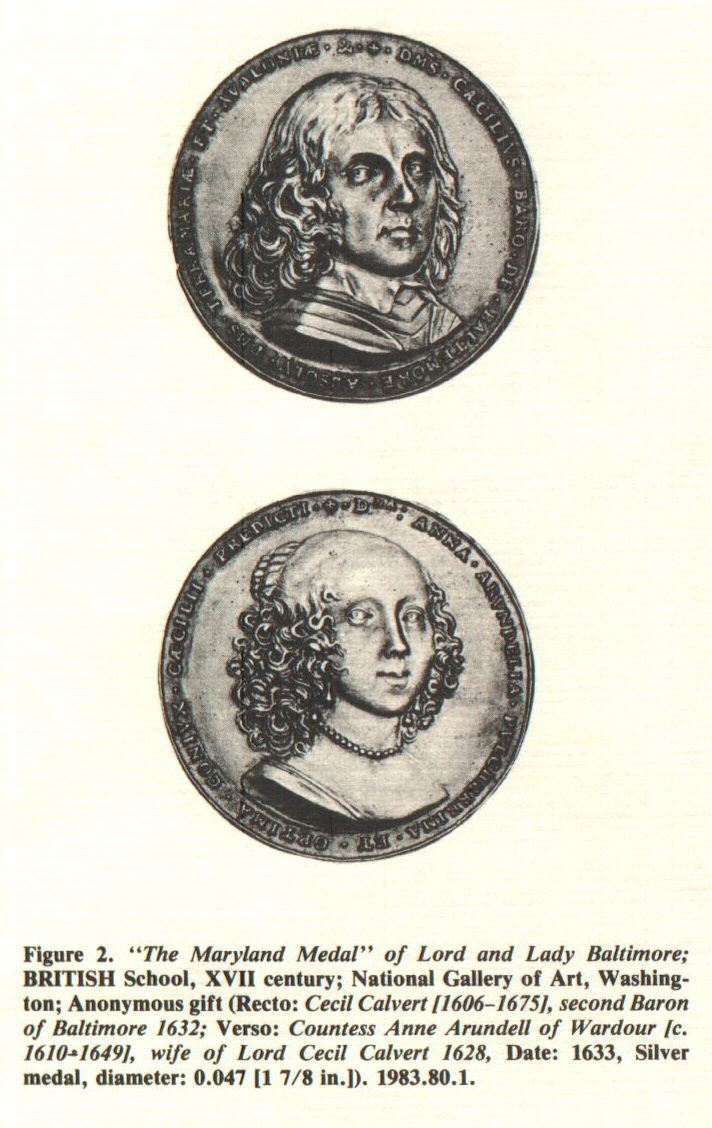

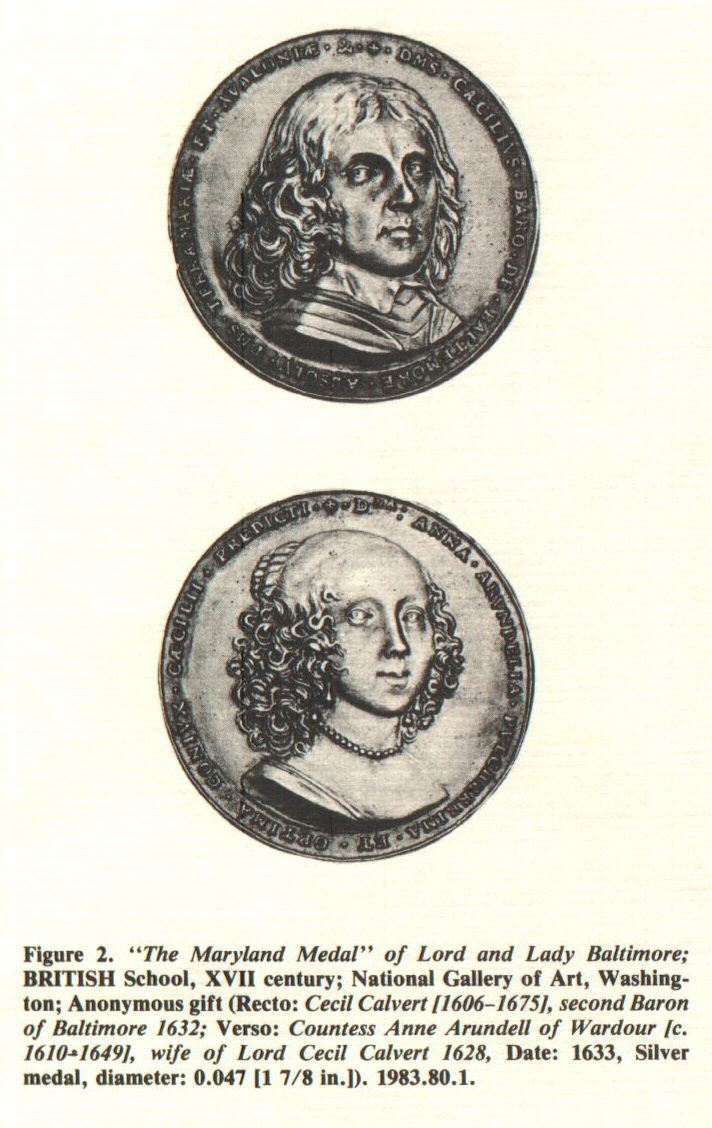

Their marriage was commemorated by the issue of a silver medal with

Cecil on one side and Anne Arundell on the other. This is the only know

contemporary image of Anne Arundell, although in 1672, long after she had

died, Cecil sent a portrait of her to his son Charles in Maryland.

This portrait of Anne Arundel now hangs in Hook House in the southern

county of Wiltshire. It once was consigned to basement storage in nearby

Wardour Castle where Anne Arundel was born. It has been across the Atlantic

more than once and probably is the one referred to in correspondence between

her husband Cecil and her son Charles. Neither Cecil nor Charles thought

it a good likeness, but Charles was pleased to have it anyway: In 1673

he wrote his father from St. Mary's City that he had

recieved ... my mother's picture which will be a great Ornament

to my Parlor and though the painter hat not done it for her advantage as

your lordship writes, yet those thinges are much esteemed here ...

Hook House, with the ruins of Wardour castle off in the

distance

Until her death in 1649, Anne resided with her husband in at least

three places, Kiplin Hall in Yorkshire, a rented townhouse in London, and

at Hook House which was built on land given to Anne by her father.

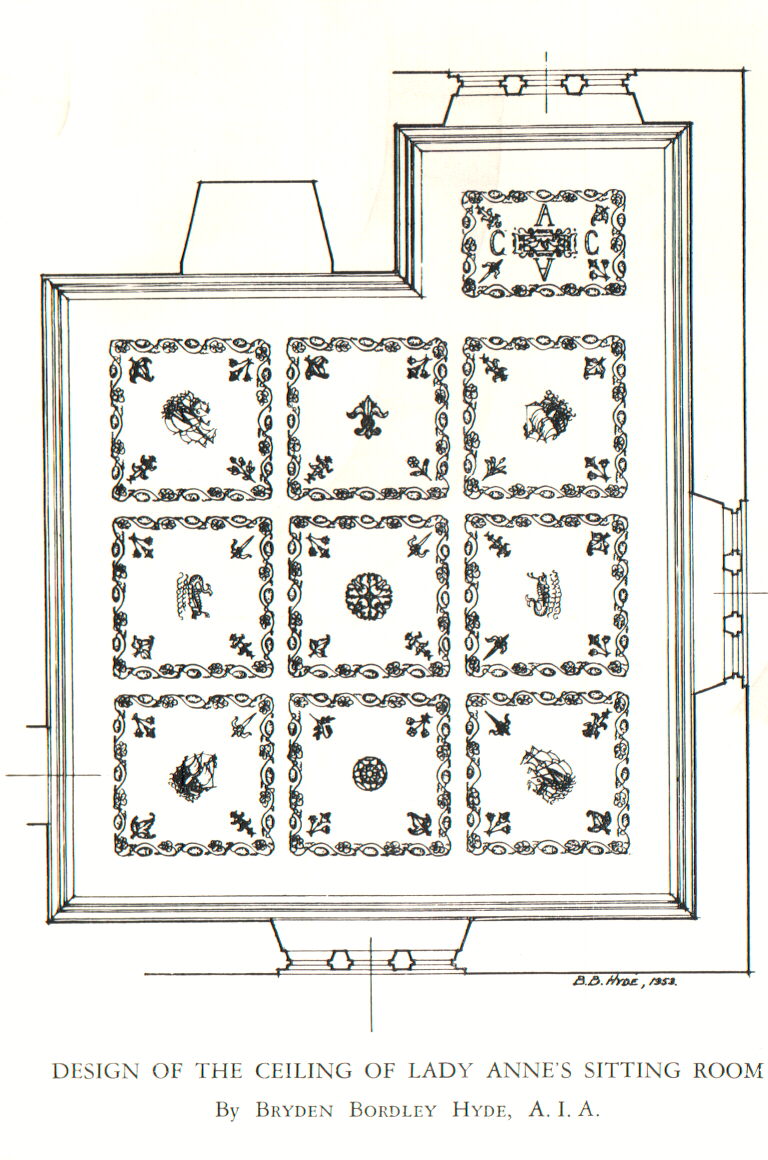

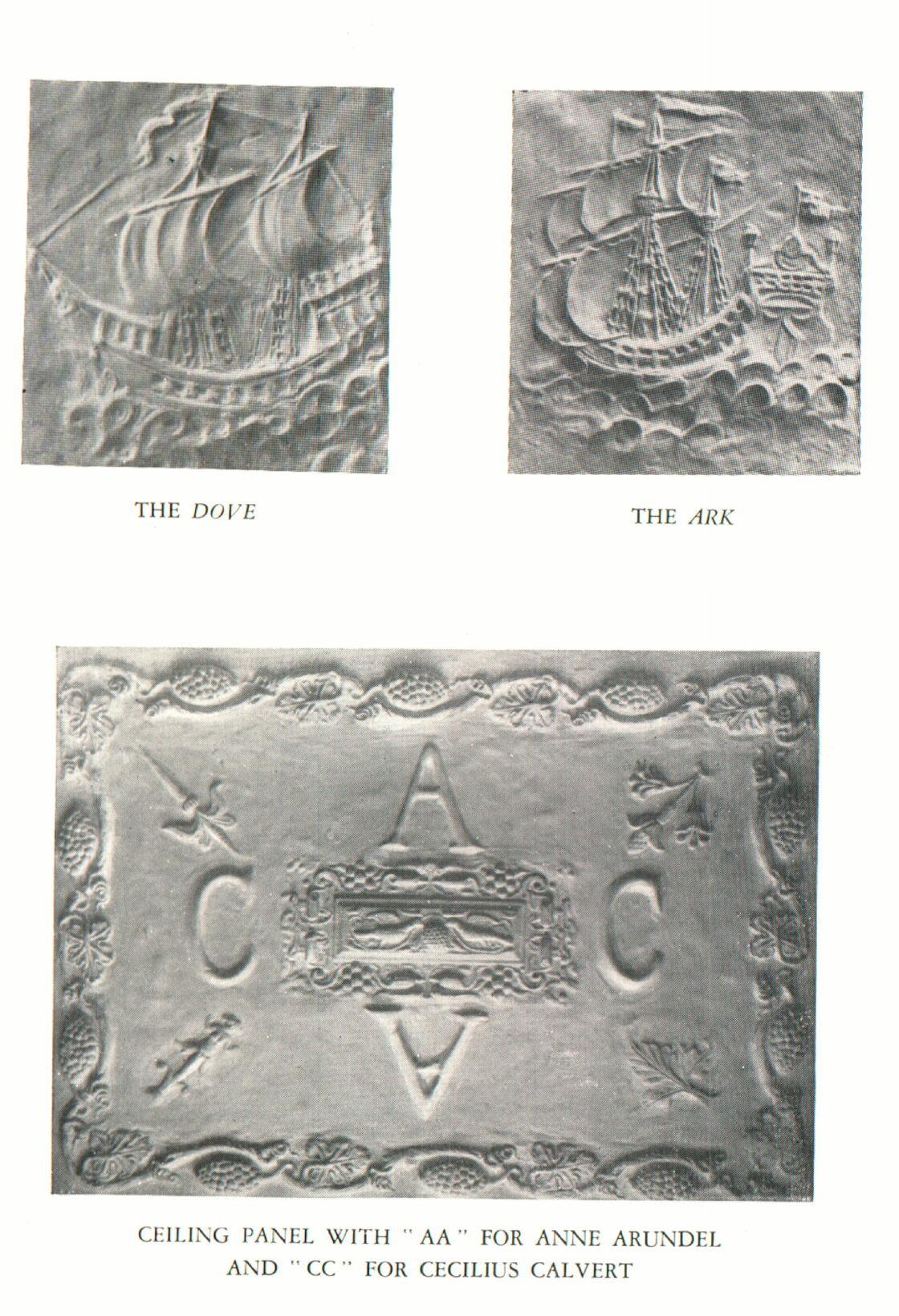

There Cecil commemorated the colony by having an ornate plaster ceiling

with their initials and reliefs of the Ark and the Dove installed

in what is now known as Lady Anne's sitting room. [12-93]

It was here also that Anne Arundell probably raised Philip Calvert as

her own along side Charles, the future third Lord Baltimore. Philip was

eleven years older than Charles. His origins are wrapped in mystery, but

it is most likely that he was born of the union of his father with the

chamber maid for whose care George Calvert braved the plague in 1630. George

may have missed his wife, and paid homage to St. Cecilia, but he did not

remain celibate for long, marrying again in 1627 or 1628, shortly before

or after Philip was conceived, only to have his second wife lost at sea.

portrait of Charles Calvert, 3rd Lord Baltimore, by John

Closterman, 12-129-4

There is no known portrait of Philip, but there are several of Charles,

his nephew, such as this one recently offered for sale. To what degree

Anne shaped the minds and encouraged the development of both is not known.

They were well cared for and well-educated. Charles remembered his mother

fondly 24 years after her death. Philip was 23 and Charles 12 when she

died. Both would prove to be strong personalities, jealous of each other,

but each in his own way careful and competent managers of the new world

venture. Philip, as his brother's emissary to a floundering colony in 1657,

brought stability and order to the affairs of government, providing careful

attention to the creation of a body of laws of estate and land administration

that have continued to serve well to the present. Charles, after an initially

rough beginning in the shadow of his uncle, became an astute politician

who kept both his faith and his lands at a time when religious toleration

was on the wane at home in England and in the Maryland colony.

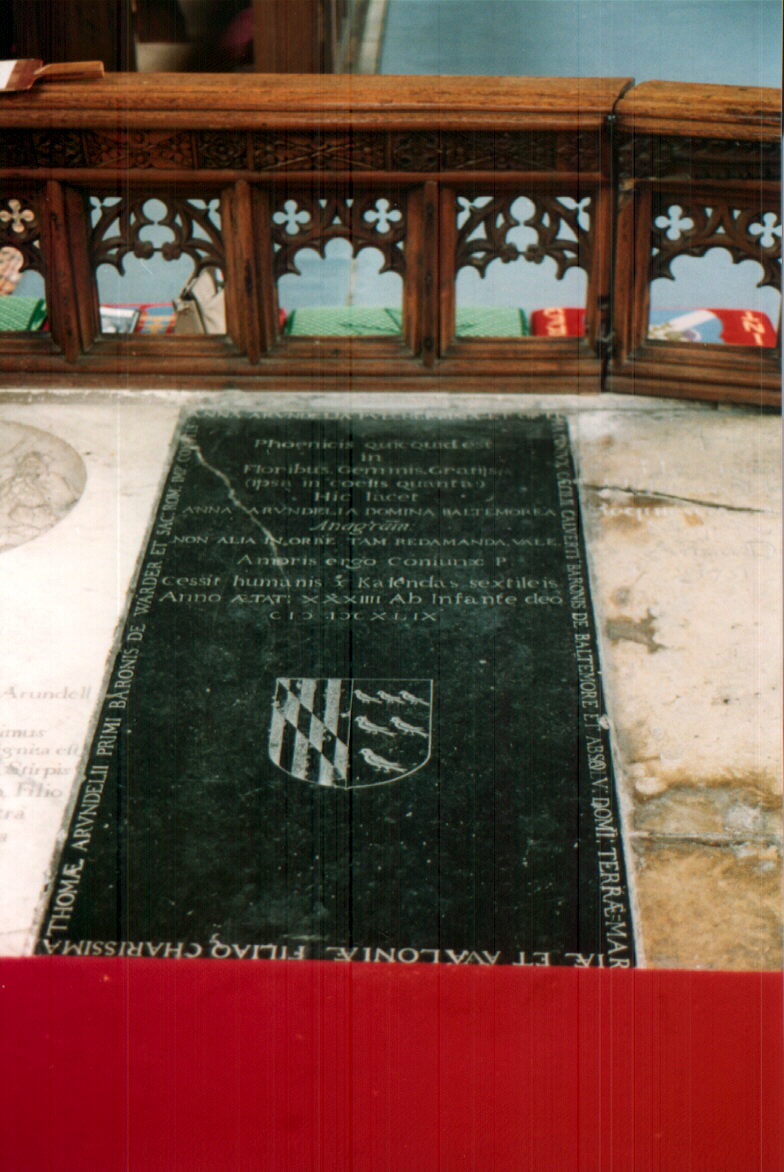

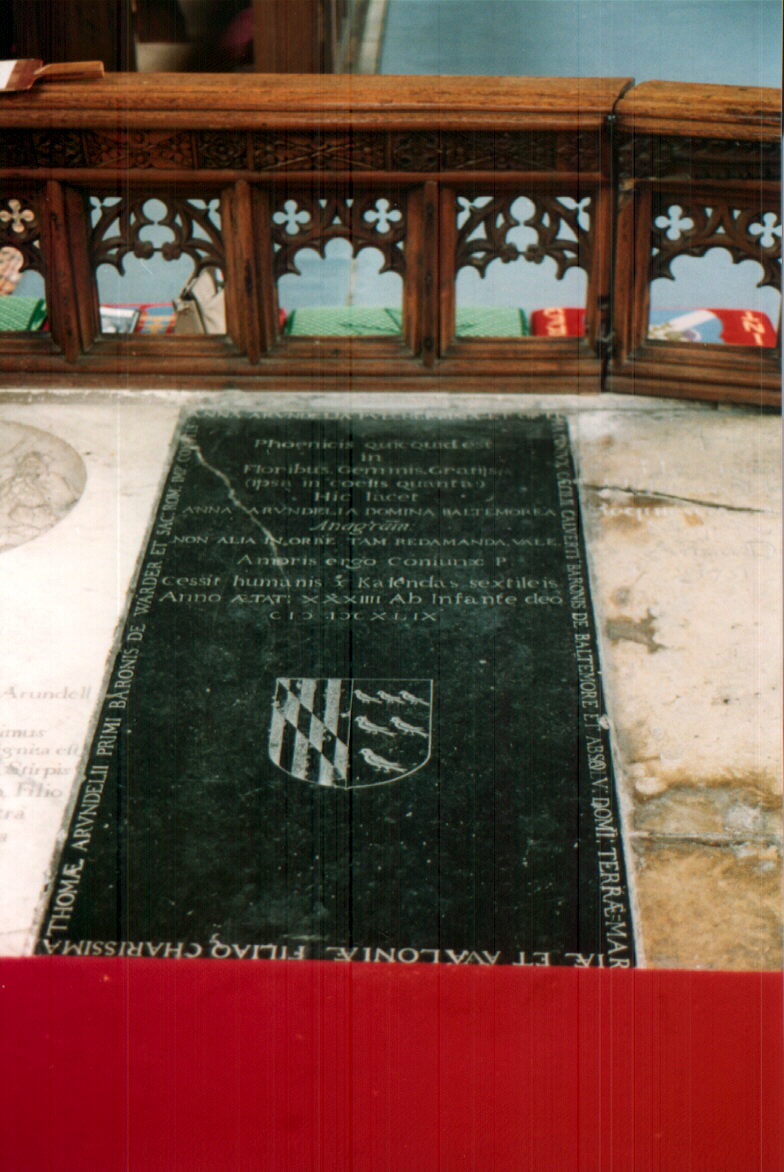

tombstone of Anne Arundel, St. John the Baptist, near

Tisbury

We will never know for certain the extent of Anne's influence, but

we can guage the material contribution her fortune made to the success

of the Maryland venture and to the life-style of her children. Without

her lands at Bournemouth there might never have been a St. Mary's. Anne

Arundell died suddenly in 1649 at the age of 34 and was buried beneath

a slate tablet before the alter of her parish church of St. John the Baptist

near Tisbury, Cecil, Philip, and Charles were left to manage alone.

Unlike his father George, Cecil Calvert seems to have chosen to not

only honor, but also to emulate St. Cecilia. He apparently remained celibate

until his death in 1675, dispatching first his brother Leonard, then his

ward Philip, and finally his son Charles to manage his colony in the new

world, when conditions at home prevented him from going there himself.

From its founding until the day he died in 1675, Cecil Calvert devoted

his life to following the spirit, and often the example of his namesake,

St. Cecilia. He preached the gospel of hard work and a just reward in the

new world.

When the colony appeared likely to fail in 1649 he even pioneered legislating

tolerance in an age of intolerance, proudly drafting in his own hand an

act of toleration. The act was a masterpiece of tact, incorporating the

harsh language of the Elizabethan laws regarding blasphemy, but carefully

allowing the practice of any religion as long as the practitioner remained

silent and did not impose his or her views on others. For nearly forty

years, years in which the colony struggled to survive, the Act of Toleration

provided a framework for success that utimately in part inspired the first

amendment to the U. S. Constitution.

By 1671, Cecil Calvert could bask in the warm glow of the praise John

Ogilby heaped upon him in his "America":

Thus this province at the vast charges, and by the unweary'd industry

and endeavor of the present Lord Baltemore, the now absolute Lord and Proprietary

of the same, was first planted, and hath since been supply'd with people

and other Necessaries, so effectually, that in this present year of 1671,

the number of English there amounts to fifteen or twenty thousand inhabitants,

for whose encouragement there is a fundamental law established there by

his Lordship, whereby Liberty of Conscience is allowed to all ...

Ogilby limited such freedoms to Christians, but Cecil Calvert did not.

Although his colonists tried to convict one Jew as having violated the

act of Toleration by proseltyzing, they failed, never to try again.

Ogilby also gave far to much credit to Cecil Calvert alone for the successes

in the New World. A whole generation of colonial leaders had been molded

by not only the example of George and then Cecil, but also by their wives

both in life and after death. Much like Saint Cecilia, the Calvert women,

while not celibate, exerted a strong influence on their husbands and their

children, teaching by example and contributing their lives and their fortunes

to their success.

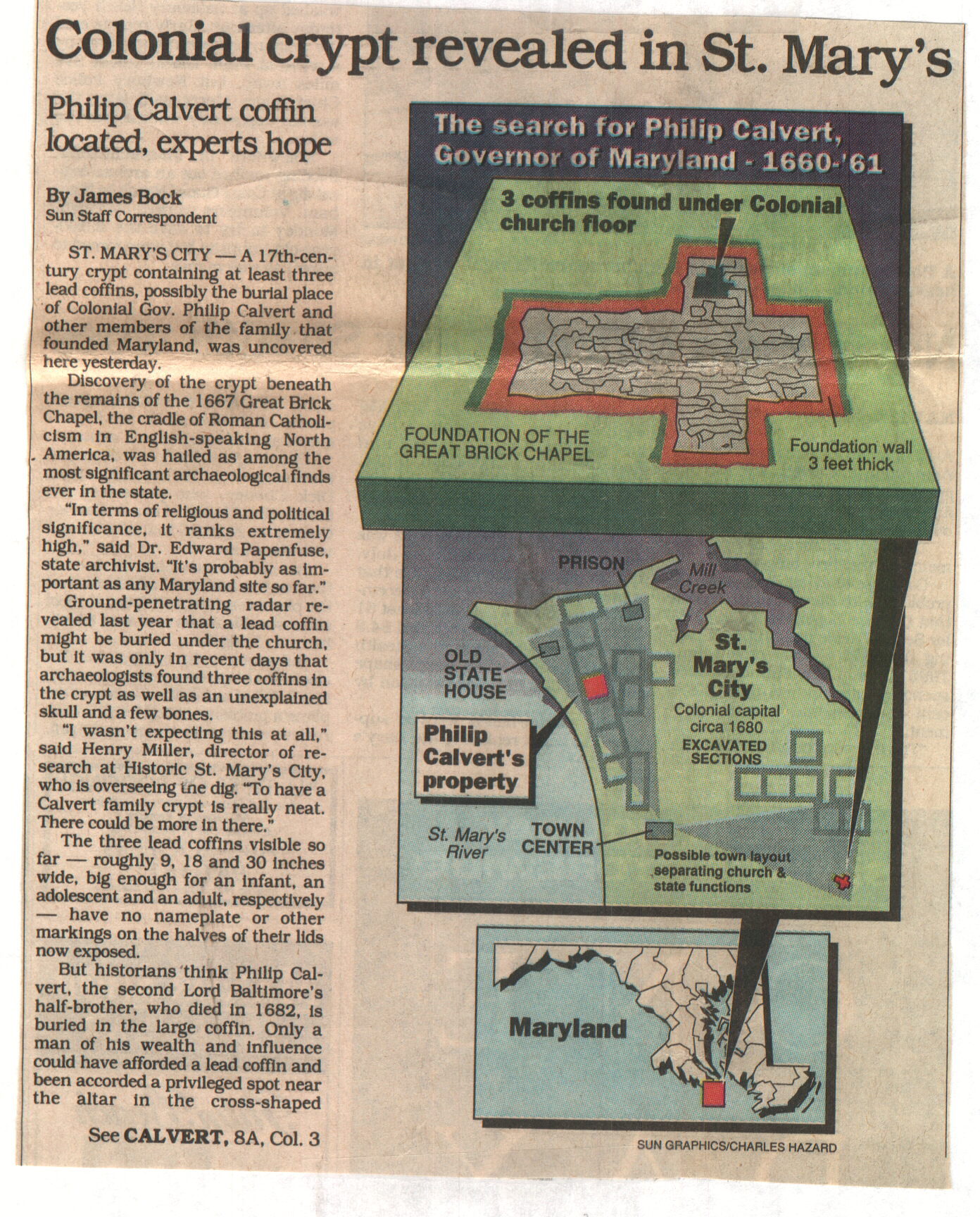

Lead coffins, St. Mary's City

Anne Wolseley Calvert

Which brings me finally to the last of the three Anne Calverts to whom

we pay tribute this evening.

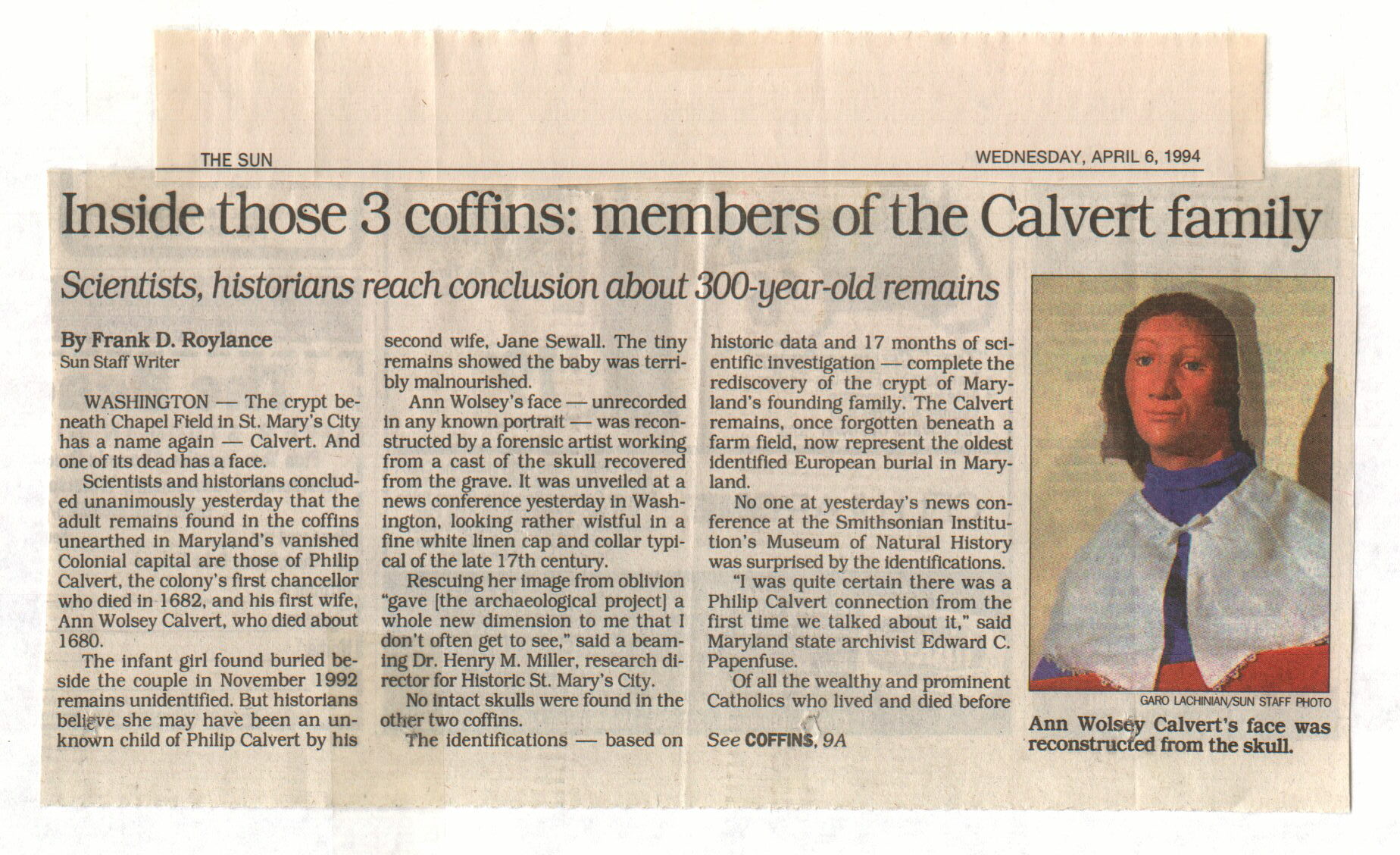

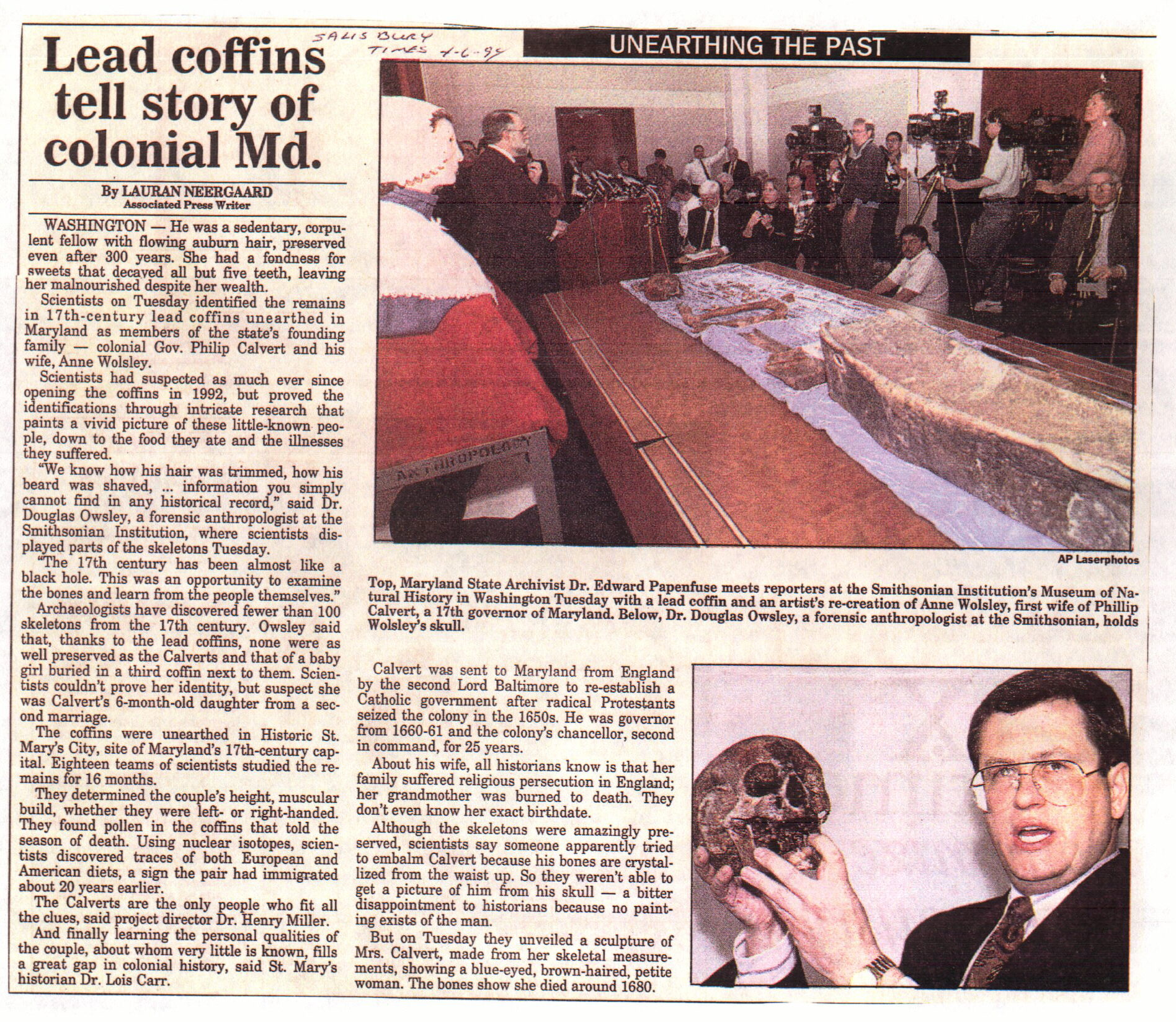

On December 5, 1990, James Bock reported in the Sun that a team

of scientists, archaeologists, and historians had begun to interpret the

remains of three people buried in lead coffins within the foundations of

probably the first brick Catholic Chapel in English-speaking North America.

The middle of the three coffins contained a woman of 55 or 60 years whose

suffering at the last must have been enormous. She was malnurished and

had few teeth. She had been in considerable and constant pain from a spiral

fracture of one leg that had only partially healed allowing her to walk

with a pronounced limp, but leaving her with two open abcesses that surely

made the last two or three years of her life perfectly miserable.

Who was this woman buried with such tender loving care- arms folded

and tied with silk ribbon, rosemary, the herb of remembrance sprinkled

lovingly over her body? All of the evidence points to Ann Wolseley Calvert,

the wife of Chancellor Philip Calvert who lay next to her in the largest

of the three coffins. She came with her husband in 1657 and died in St.

Mary's City two years before him, in about 1679 or 1680.

We now know that she suffered greatly and we know much about her state

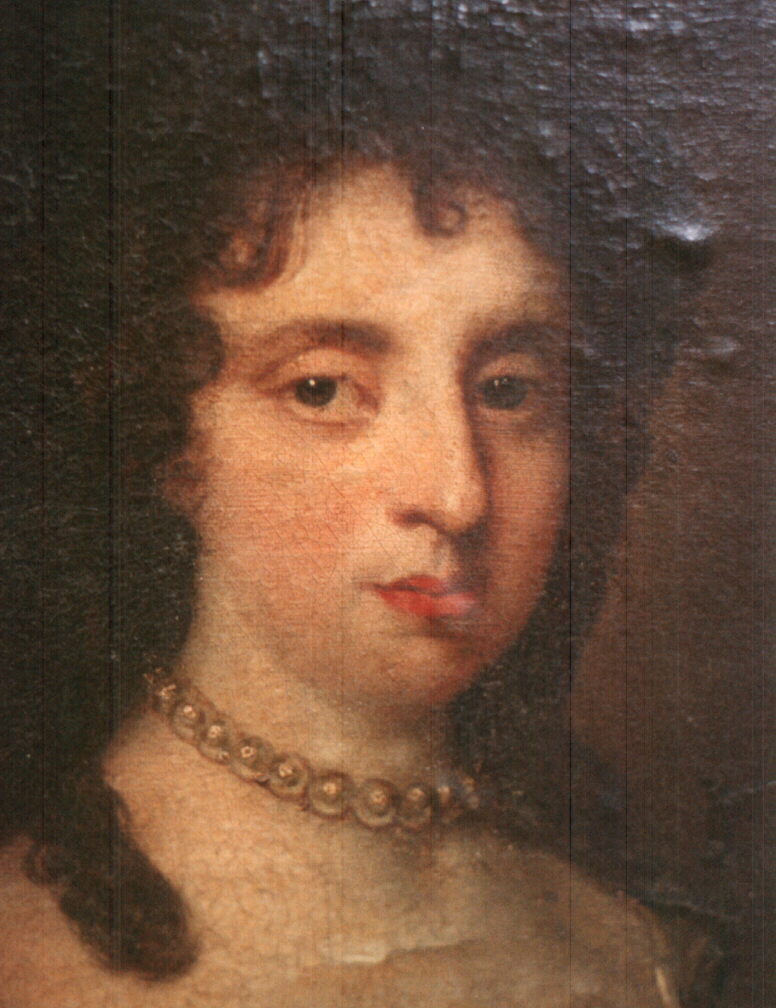

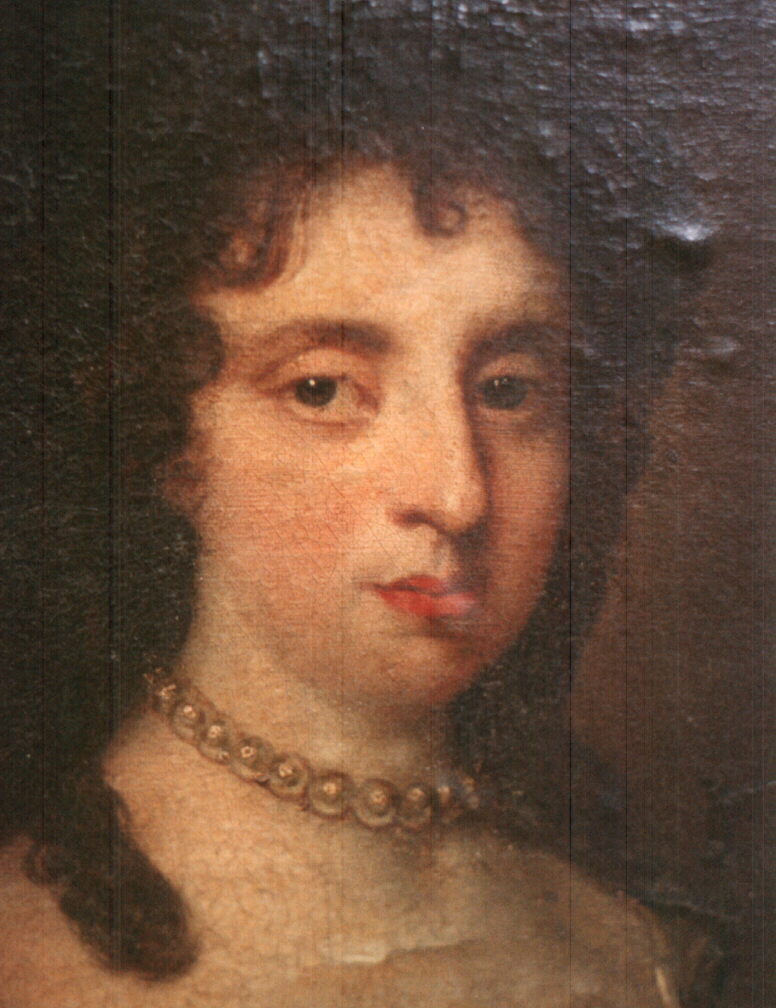

of health, but can we also put a face to her memory?

From her skull, a forensic pathologist reconstructed the facial muscles

and overlaying tissues to produce a striking likeness. How close she came

to capturing the real Anne Wolsely we will never know for certain without

a contemporary image. We do have a new clue however, the story of which

is interesting in itself.

In the 1750s a relative of the Wolseleys came to Annapolis to live.

She brought with her a painting of her grandmother the neice and namesake

of Anne Wolseley, Anne Wolseley Nipe. When she died the painting passed

to her daughter and then to her granddaughter. It then skipped a generation,

passing to her great-great granddaughter, the wife of the Honorable George

Hunt Pendleton. Pendleton served in Congress, ran as George McClellan's

running mate against Abraham Lincoln in 1864, authored the Pendelton Civil

Service Act and was rewarded with an Ambassadorship to Germany. Mrs. Pendleton

took the painting with her to Germany, removing it from Annapolis where

it had been on display for about 150 years.

By 1929 it had disappeared from sight. Because it was of a close blood

relative to Anne Wolseley, and might be useful in the reconstruction her

image as well as in the hunt for family DNA, two consumate researchers,

Jane McWilliams and Elaine Rice, were assigned the task of tracking it

down. They managed to sort out the innumerable relatives that to whom it

could have descended, knowing that in all probability the family tradition

of bequeathing it to daughters would have continued. Unfortunately there

were a large number of candidates for whom there were no addresses and

the hunt ground to a halt. Then by chance, in the lunch room of the State

Archives Jane and Elaine happened to be talking with a senior member of

the staff who had spent her childhood in a small town in Pennsylvania.

When Jane mentioned that one of the possible heirs was named Joline and

had come from Pennsylvania, the staff person mentioned that her childhood

neighbors had had that name and offered to give them a call. They proved

to be none other than the descendants of Anne Wolseley's niece. They didn't

own the painting, but thought they knew who did, providing the telephone

number of relatives in California. The family was so delighted to receive

Jane's call and to learn about the interest in the painting that they donated

it to the State Archives, returning it again to Annapolis. From generation

to generation the women descendants and close relatives of Anne Wolseley

Nipe had carefully preserved both the memory and the artistric rendition

of Anne Wolseley Nipe. Now it has a home among the collective memories

of our colonial past at the Archives where it joins a revived interest

in the role of women who helped formulate what was, and what is Maryland.

Although genetically linked to her name-sake there still remained the

question of how much Anne Wolseley Nipe resembled her Aunt?

I leave that for you to ponder, but to my eyes there are some striking

resemblances, especially given the fact that the portrait was probably

a marriage portrait designed to show off the best qualities of the sitter,

while the reconstruction was not an artistic embellishment of fact. To

put it bluntly, as a recent member of the English branch explained to Elaine

Rice, the Wolseleys were known for their big noses.

In many respects, Anne Wolseley Calvert, whose own family had suffered

persecution in England for their adherence to Catholocism, represents everywoman

of 17th Century Maryland with her strong determination to make her way

in a forbidding world filled with travails not unlike those of Maryland's

neglected patron saint, St. Cecilia.

While the records are for the most part silent about the example Anne

Wolseley Calvert set for those about her, we are left with one tantalizing

piece of evidence that suggests the devotion she could inspire. Her husband

spent his life attempting to make the colony of Maryland a reasonably safe

and secure place to live, a place where men, who died young and often with

minor children, could be assured that the state would properly administer

their estates for the benefit of their widows and their children. He did

so with the help of a number of devoted clerks, the bureaucrats of their

day, often providing them with lodgings in his own home. When his longtime

bachelor clerk, Michael Rochford died in 1679, Rochford chose not to honor

his employer, but his employer's wife, Anne Wolseley. Out of a meager estate,

he left his most precious possession, his silver watch to Ann, a touching

tribute to a woman who had suffered much but who also seems to have been

able to have shown kindness to others.

Not everyone agrees that we should go to such lengths as peering into

coffins to reconstruct the past. Indeed an individual who may be a Calvert

descendant felt compelled to write expressing his concern over what he

perceived of as a desecration of a grave. He closed his letter with the

familiar blessing "Eternal rest grant unto them O Lord. Let perpetual light

shine upon them. May they rest in Peace."

I tried to explain in reply that until we did the historical research

there was no connection with the Calverts and that from the remains alone

their could not be. Only by linking the scientific evidence secured from

many different disciplines with the fragmentary written evidence that survives

could identification of the remains be nearly certain. I said nearly, because

so much of the literary evidence has been lost. Nowhere in the records

available today, for example, is there reference to these graves as being

those of Anne, Philip, and an unnamed female child.

Should we engage in such reconstruction of the past from actual human

remains? That is a philosophical question which in my opinion is best answered

yes. If Wehad put as much into life for the benefit of others as Philip

and Anne did, if we had suffered as much as Anne and that five month old

girl did, I think I would like the world to know it and not be forever

forgotten in a lead coffin under an oft-ploughed corn field.

When Hamlet contemplated the skull of his friend Yorick, he did so for

good reason. When with care and good taste we examine the remains of those

who gave so much so that we could live the good lives we do, we do so for

good reason as well. "Alas Poor Philip" and Ann, we should. Indeed in many

respects Anne and the young girl represent everywoman and everychild. We

owe it to them and to ourselves to pay them respectful tribute, not to

ignore them. It is not a desecration so to do, it is a celebration, the

final act of which should be a respectful re-interment in the crypt of

a reconstructed chapel on the site of the earliest Catholic chapel in English

speaking North America. But to celebrate we need to understand why, who

and how, with whatever evidence remains for us to examine. Only then can

perpetual light shine upon them and only then can they truly rest in peace.

Perhaps it is also time to lay to rest another matter which seems to

recur from time to time in the press: changing the unofficial state motto

from the Calvert's Fatti Maschii Parole Femine, to something as

historic but less controversial. No matter how hard John Florio or his

enthusiasts try, it continues to be translated

Words are women, deeds are men,

instead of what Florio intended,

gentle words, strong deeds.

Sometimes new and different interpretations of the meaning of the past

prove less persuasive than anticipated. People continue to believe what

they want to believe despite a growing body of evidence to the contrary.

That too is the challenge of history.

Fortunately for those uncomfortable with fatti maschii parole femine,

an equally historical phrase associated with the Calverts offers itself.

It is one which encircled a contemporary medal cast to honor their achievement

in the new world.

About 1632 Cecil Calvert had a medal struck with a map of Maryland

on the obverse. Surrounding the outline of the Bay and a solitary Calvert

shield is a latin phrase worthy of St. Cecilia, patron Saint of not only

music, but also the blind:

As the sun thou shalt enlighten America.

Perhaps "As the sun thou shallt enlighten America" would satisfy those

who clamor for something better or something new, assuming of course, as

the man responsible for the death of St. Cecilia, Marcus Aurelius, is alledged

to have written,

we are all working together to one end, some with knowledge and

design, and others without knowing what they do.

But if we change it, we will also be detaching ourselves further from the

rich history of the contributions of the three Anne's, especially Anne

Mynne, whose concern for a gender neutral world was centuries ahead of

her time.

Writing history is an exercise of contemplation and imagination, of

projecting back in time in an effort to understand why and how people behaved,

how they viewed the world about them, and what the major influences were

that affected their daily lives. What I hope I have done this evening is

to challenge you to think differently about the past, to help you see that

in our history there can be new ideas about the meaning of symbols and

the interpretation of evidence, both familiar and recently unearthed. As

long as we are willing to re-examine what we know, and how we know it with

an open mind, the adventure will not only be an exciting one, but an illuminating

one as well.

Thank you

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()